L.B. Lawson and James Scott Jr., Can't Love Me and My Money Too.

L.B. Lawson and James Scott Jr., Scott's Boogie.

L.B. Lawson and James Scott Jr., Flypaper Boogie.

"To me, a lot of the early stuff that I recorded--the Blues--could be classified as masterpieces. With the jet age coming on, with cottonpicker machines as big as a building going down the road...I knew that this music wasn't going to be available in the pure sense forever," Sam Phillips, 1984.

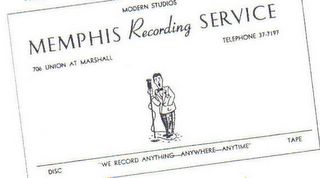

In January 1950, a 27 year-old disc jockey and amateur recording engineer named Sam Phillips opened the Memphis Recording Service, on 706 Union Avenue. His plan was to record local blues and country artists and to sell the sides to independent labels, and he soon established relationships with the Los Angeles-based Bihari brothers, who owned Modern Records and RPM, and Chicago's Chess brothers, who were gearing up their self-named label.

Phillips was convinced that rawer-sounding country and blues (which at mid-century were still sold primarily to rural white and black markets, respectively) could reach a wider audience. It would take him four years until he found his passport in the form of a young man who, at the time Phillips began recording, was idling his hours away at Humes High School. But in his search, Phillips recorded many blues players at the peak of their powers, and began documenting on acetates the gestation process of rock and roll.

Phillips soon gained a reputation with blues artists as someone who treated them fairly, with respect, and who made no attempt to sweeten their sound. "I tried to get them to record what they had, and to bring out of them what they were," he would tell Martin Hawkins decades later. "This is difficult for me to explain, but I felt it so strongly it was almost a religious belief."

At some point in 1951, a group of local musicians known as the Scott Jr. Blues Rockers went into 706 Union and recorded four sides that stayed in the Sun vaults for 35 years. These records, which apparently even Phillips thought were too raw for release, are a lost founding document of rock & roll: it's the sound of the Rolling Stones' Exile on Main Street, but two decades earlier--basement music; Satanic juke joint blues filled with insistent rhythms. Music as an accidental conspiracy--the two guitars, James Scott's lead and Charles McLellan's rhythm, scrap and tear at each other, Robert Fox's drums thrash along behind them.

"Can't Love Me" is a standard blues overturned by its performers. Scott's vicious lead guitar kicks it off, and then L.B. Lawson reels into the first verse, sounding a bit drunk, giving way in turn to a boogie break in which McLellan fuels the rhythm, as the drummer is shuffling around by himself in the corner. Lawson stumbles back in. "Tell me babe, what's a matter with you last night?" he slurs at his woman. "We had to hurry home 'cos you know we got to fight." And the guitars spar off.

"Flypaper Boogie" and "Scott's Boogie" are even more astonishing. In "Scott's Boogie," Scott is spiralling around until he catches the rhythm McLellan is brewing. About forty seconds in, the guitarists seem to have completely dispensed with the drums, which are again just murmuring in the background; McLellan drives the beat and Scott dances on it. "Flypaper Boogie" goes deep into a primal blues state, where Scott strings out brutal, simple lead lines while McLellan hovers on the beat until he starts coming after Scott in a locomotive attack. Both tracks end quickly and sloppily, with a clatter, as if the players suddenly have lost interest.

Who were these men? Lawson is a historical cipher, about whom almost nothing is known, not even what his initials stood for. One site lists him as being born in 1929, relying on unknown sources; he possibly came from Enid, Mississippi. The fourth track the group recorded at Sun (much inferior to the others) was "Got My Call Card," which suggests Lawson, if he wrote the lyrics, was about to be drafted into the Korean War. He never recorded again, to the best of my knowledge, and is apparently dead.

The record is a bit clearer on Scott. Born in Adabina, Mississippi in 1913 (or 1923), and an alleged classmate of John Lee Hooker, Scott formed the Blues Rockers in 1948. After the Lawson session, Scott appears to have worked as a journeyman blues guitarist throughout the 1950s and 1960s, backing Boyd Gilmore, among others. He died in 1983.

Most of these tracks cannot be purchased at present (though "Flypaper Boogie" is available on this compilation), so consider this post a public incentive--someone really needs to put the Lawson/Scott sides out, and do more investigative work than this paltry effort. The tracks were first released on the colossal Sun Records: The Blues Years, a 9-LP box set issued in 1986. A decade later, the UK's Charly Records updated the set to CD, including more unreleased tracks--thus making the set even more invaluable, and naturally it soon went out of print. Much of this post's information is derived from the Charly set's booklet, written by Martin Hawkins, Colin Escott, Neil Slaven and Roger Dopson.

No comments:

Post a Comment