Fairport Convention, A Sailor's Life (alternate take).

Clifford Jenkins, The Sailor's Alphabet.

World Party, Ship of Fools.

As dark night drew on, the sea roughened: larger waves swayed strong against the vessel's side. It was strange to reflect that blackness and water were round us, and to feel the ship ploughing straight on her pathless way, despite noise, billow and rising gale. Articles of furniture began to fall about, and it became needful to lash them to their places; the passengers grew sicker than ever; Miss Fanshawe declared, with groans, that she must die.

'Not just yet, honey', said the stewardess. 'We're just in port.' Accordingly, in another quarter of an hour, a calm fell upon us all; and about midnight the voyage ended.

Charlotte Brontë, Villette.

To walk or to ride is to cast one's lot with the earth, with its rhythms, its reassurances and miseries; to sail is to venture on uncertainty. For a good part of our history, to go to sea was to go outside of time ("the sea is as near we come to another world," Anne Stevenson), take severance from life, to put oneself at the mercy of unknown, awful powers. Sea travel transforms, it embodies the whims of fortune; each trip is a gamble, typically for low, sometimes for great, stakes.

Where to begin with what Swinburne called the great sweet mother? Here are two different tacks:

"The Seafarer" is one of the oldest of English poems; it was first written down in the Exeter Book, circa 900 AD, but it likely circulated years before. Its author is, unsurprisingly, unknown, and one wonders whether the author had been a sailor or perhaps, as many great artists do, simply had the gift of fraud--someone, like Samuel Coleridge when he wrote "Rime of the Ancient Mariner," who had never gone to sea.

The poem is sung by a sailor, one who must keep "the arduous night watch" on deck, where he thinks, bitterly, of those snug on land:

...he who is used to the comforts of life

and, proud and flushed with wine, suffers

little hardship living in the city,

will scarcely believe how I, weary,

have had to make the ocean paths my home...

the prosperous man knows not

what some men endure who tread

the paths of exile to the end of the world...

A half-millennium later, an English/Scottish ballad eventually known as "A Sailor's Life" came into being. Sung throughout Britain's age of sailing, the ballad had fallen into shadow when Fairport Convention revived it for their 1969 album Unhalfbricking.

While the official take attempts to convert the ballad into a raga, with the song based around a drone (primarily carried by Dave Swarbrick's fiddle), there was an earlier take recorded during the album sessions, one that would have been lost had not a fan managed to find an acetate recording of it.

Swarbrick wasn't on this take. The players seem unsure at first: the guitars meander, the bass tries at times to set off on a direction, gets pushed back, the drums roll about in the background. Then Sandy Denny begins with what, at first, sounds like the sentiments of a typical sea shantey:

A sailor's life

It is a merry life...

Then a breath, and then she spits at the notion:

He robs young girls

Of their hearts' delight.

The song coheres, the story that follows is conveyed in jump cuts, in shards. We're on the docks of a seaside village, watching two dozen young men compete (doing what, we're not told--tying knots? climbing masts?) to join a fleet of Navy ships in the harbor. The singer stands in the crowd, prideful--the boy that she loves is a natural sailor, the finest--and already half-knowing her choice has doomed her.

Another jump--some years, some months pass, and she goes to her father and begs him to build her a boat, so she can sail after her lover. An old man works on the beach, wearily hammering together a keel, knowing he's building a coffin for his daughter, while she watches, sitting upon a pile of sea-washed stones. Then, at once, she's out upon the deep, drifting from ship to ship, asking for her William.

It ends as you might expect. Her sailor has drowned off an island that the girl spies from her boat. At once, the perspective changes: much of the story has been conveyed through the girl's eyes, but now we stand on deck with the seafarers who watch as, in despair, she drives her boat against the rocks, joining her lover in oblivion, sinking blissfully beneath the waves.

Then Richard Thompson delivers a requiem. On Watching The Dark.

Hoist the Blue Peter

The Great Eastern, under construction.

They that go down to the sea in ships,

that do business in great waters;

these see the works of the Lord,

and his wonders in the deep.

For he commandeth, and raiseth the stormy wind,

which lifteth up the waves thereof.

They mount up to the heaven,

they go down again to the depths:

their soul is melted because of trouble.

They reel to and fro,

and stagger like a drunken man,

and are at their wit's end.

Then they cry unto the Lord in their trouble,

and he bringeth them out of their distresses...

Psalm 107: 23-28.

Traveling by ship, whether over sea, lake or river, is the last of the three ancient modes of transportation--those we have used since the dawn of civilization, those that will be left to us should we ever do anything catastrophic to ourselves.

Sailing at its most basic--shore-hugging by raft, or sailing down river in a sealskin boat--likely antedates the domestication of horses. The Chinese, Indians, Arabs and Malays were among the first sailors, who mastered the seasonal winds of the Indian Ocean and the South Pacific, establishing trade networks, their navigational charts seashells sewn with palm-fibers.

And the master navigators of the ancient world were the Polynesians, who, with the trade winds directly in their faces, built strong canoes and fore-and-aft rigs suited for windward voyaging. Long before most scholars and scientists, Polynesian sailors knew the world was round, and had discovered five planets, using them, along with what they call the fixed stars, as their primary means of navigating. The Polynesians made it to Hawaii, where they cut ocean charts on the shells of round bottle gourds; they may have gone as far as Peru, as Thor Heyderdahl famously argued.

Odysseus' knees grew slack, his heart

sickened, and he said within himself:

'Rag of man that I am, is this the end of me?

I fear the goddess told it all too well--

predicting great adversity at sea

and far from home...

I should have had a soldier's burial

and praise from the Akhaians--not this choking

waiting for me at sea, unmarked and lonely.'

The Odyssey, Book Five.

Roman battleship

Europe had its share of great sailors, such as the Phoenicians, but everyone from the Greeks to the Barbary pirates had to contend with being based on the Mediterranean, a stormy, gluttonous sea that could never be fully relied upon. What is Homer's Odyssey but a depiction of a calamity-plagued twenty-year voyage between Turkey and Greece?

Dropping anchor at Angkor Wat

Beyond the Mediterranean, the Vikings, the first in the North Atlantic to master those grim seas, rose to power, sailing to America and having little use for it. But who first sailed to America from Europe? Tim Severin, a British historian, became convinced that Saint Brendan and a crew of Irish monks had done so sometime in the 6th Century. To test his theory, he had a replica of a 6th Century coracle built--some 36 feet long, with two masts with square sails, its hull covered by oxhide skins, all of it held together with two miles worth of leather thongs.

On 17 May 1976, Severin and four crew members sailed from Ireland and reached Reykjavik two months later. The following summer, they sailed across the Denmark Strait, survived a horrific southwesterly storm that could have driven them into the Arctic, and, six weeks out from Iceland, Severin's crew reached Newfoundland. If the saint had not made the voyage, at least his disciple had.

Oseberg Ship, Norway.

Two more sea overtures:

In the '50s, the archivist Peter Kennedy went around the seaside towns of the British Isles and recorded a number of fishermen--his work captured a waning generation of Edwardian sailors singing shanties, often accompanying themselves on squeeze boxes, with a friend sometimes chiming in on the choruses.

"The Sailor's Alphabet," from anchor to zinc, was recorded ca. 1955 on St. Mary's, the largest of the Isles of Scilly, and performed by a lifeboat fisherman named Clifford Jenkins; it can be found on Sea Songs and Shanties (and eMusic).

The Ship of Fools has its origins in the Middle Ages, when, according to Foucault's Madness and Civilization, a common method for cities like Paris to reduce the population of the insane was to herd them on ships and send them off to sea or down the river. A modern version of this strategy is known as "Greyhound therapy."

In 1494, the German satirist Sebastian Brandt wrote Narenschiff, an allegory in which a boat laden with the insane is steered to the fool's paradise of Narragonia. According to the Oxford Companion to English Literature, "the popularity of the book was largely due to the spirited illustrations, which show a sense of humour that the text lacks." Still, Narenschiff kicked off a wave of 'sailing fools' literature, such as Cock Lovell's Bole, in which a collection of wild tradesmen roam around England.

A latter-day version is on World Party's Private Revolution, released in March 1987.

Shanties

The Mekons, Shanty.

Bob Roberts, Windy Old Weather.

This morning the wind changed, a little fair. We caught a couple of dolphins and fried them for dinner. They tasted tolerably well. These fishes make a glorious appearance in the water...every one takes notice of the vulgar error of the painters, who always represent this fish monstrously crooked and deformed...the sailors gave me a reason, though a whimsical one, that this most beautiful fish is only to be caught at sea, and that very far to the Southward, they say the painters willfully deform it in their representations, lest pregnant women should long for what it is impossible to procure for them.

Benjamin Franklin, journal of sea voyage, 2 September 1726.

Sea travel, of course, has its trademark music--the shantey, one of the oldest surviving types of work song, meant to be sung in unison, with roaring choruses and filthy lyrics.

Shanties were often work-specific, their timing designed to make sailors move in rhythm--pulling ropes, working pumps, rowing. (Songs for leisure were sometimes known as "forebitters," because they were often sung while the crew was lounging on the 'bits’, the large wooden cleats to which the ropes were tied.)

Shantey lyrics, improvised and rigged to fit whatever job was required--long narratives for tasks like weighing anchor, shorter songs with brief verses for tightening ropes--were often designed to let sailors vent about the petty barbarities they endured. Cooks, captains and the sailors of other nations (for the English, the French and Spanish were prime targets) were set up for vicious abuses. The songs were often led by a shanteyman, picked for his good sense of rhythm and, most importantly, having a voice that could bellow across the decks.

No man will be a sailor who has contrivance enough to get himself into a jail; for being in a ship is being in a jail, with the chance of being drowned…A man in a jail has more room, better food, and commonly better company.

Samuel Johnson, 1759.

"Shanty," which leads off with the shipping news, is off the Mekons' great 1986 record The Edge of the World.

Bob Roberts, who sings the traditional shantey "Windy Old Weather," was the last of the UK sailing barge skippers, according to Peter Kennedy, who recorded him during the '50s. Again on Sea Songs.

Quests to Cruises

Judy Collins, Bonnie Ship the Diamond.

Bob Dylan and the Band, Bonnie Ship the Diamond.

Frankie Ford, Sea Cruise

Billie Holiday and Her Orchestra, A Sailboat in the Moonlight.

Brian Eno, Julie With...

I have a boat here. It cost me £80 and reduced me to some difficulty in point of money. However, it is swift and beautiful and appears quite a vessel. Williams is captain, and we drive along this delightful bay in the evening wind under the summer moon until earth appears another world. Jane brings her guitar, and if the past and future could be obliterated, the present would content me so well that I could say with Faust to the passing moment, "Remain thou, thou art so beautiful."

Percy Bysshe Shelley, letter to John Gisborne, 18 June 1822. Shelley would drown while sailing twenty days later.

Though sea travel eventually divulged some of its mysteries, with the introduction of the magnetic compass in the 12th Century and the invention of longitude in the 18th, sailing never quite lost its sense of the epic. The great voyages of antiquity were succeeded by trips of discovery and conquest, whether the Portuguese, hugging along the West African coast to the Cape of Good Hope and discovering the trade winds, or Columbus and crew stumbling upon Hispaniola.

Re-enactors rounding Cape Horn, 1991

Or Fernando Magellan, in 1519, who, after making it past Cape Horn, and having a great sense of theater, brought his fleet together and had the one surviving priest (it had already been a rough voyage, and would get worse) stand on the poop deck, holding aloft a crucifix while every sailor bowed. Then Magellan, hoisting aloft a flag that the Emperor Charles had given him, named the new ocean the Mar Pacifico, since its waters were so calm and placid that morning. And then Magellan drowned! (No, seriously, he was just speared to death a few years later.)

In maritime cultures like Britain, Portugal and, later on, New England, sea travel was so entwined with life that the deep seemed a permanent backdrop. As Jonathan Raban wrote of Shakespeare’s works, “the sea exists as a magical realm, a reservoir of glittering hopes and figures, like a mirror image of the triumphant and boundless imagination itself." And the English language is littered with dead nautical phrases. You can likely list dozens--by and large, to keep things above board, to reach the bitter end (referring to the last extremity of the anchor-chain), to be taken aback, to remain aloof (deriving from luffing, when a boat sails hard into the wind to keep away from a lee shore), to bear down, to show your true colors, to toe the line, etc., etc.

First convoy through Suez Canal, 1875.

Think of all the great ships of legend and history, each serving in the imagination as dollhouse empires, floating societies, emblems of war, wandering islands of hope, harbingers of catastrophe--the Argo, the Beagle, the Pequod, the Mayflower, the Niña, Pinta and Santa Maria, the Maine, the Endeavor, the Golden Hind, the Flying Dutchman, the Marie Celeste, the Bounty, the Graf Spee, the Achille Lauro, the Exxon Valdez.

Ships at a distance have every man’s wish on board. For some they come in with the tide. For others they sail forever on the same horizon, never out of sight, never landing until the Watcher turns his eyes away in resignation, his dreams mocked to death by Time. That is the life of men.

Zora Neale Hurston, Their Eyes Were Watching God.

Before it was captured in a ballad, “Bonnie Ship the Diamond” was an actual ship, a Scottish whaling vessel that was lost at sea, most likely in 1819. (Debate on whether the Diamond was foundered in 1819 or 1830 here.) Like many Scottish and Irish whalers of the time, the ship fished in the Davis Strait, west of Greenland; that's likely where it sank, lost to icebergs.

“Bonnie Ship the Diamond" was revived by a number of folk musicians in the late ‘50s and early ‘60s. Judy Collins' version is on 1962's Golden Apples of the Sun: the last verse, in which Collins imagines all the village boys returning home in a ship heavy with whale oil, and then making beds and, latterly, cradles rock, is human happiness at its most basic--a lie, as it turns out, but a happy one.

“Bonnie Ship the Diamond” was also one of the first songs Bob Dylan recorded with the Band in the summer of 1967. All that Dylan retains of the standard lyric is the chorus--his Diamond steers past Greenland, heading down past the equator, stopping in Mexico, struggling around Cape Horn, sailing forever, out into the deep. It's one of the unreleased Basement Tapes.

At eight we sailed for Liverpool in the wind and rain. I think it is the salt that makes rain at sea sting so much. There was a good-looking young man on board that got drunk and sung 'I want to go home to Mamma.' I did not look much at the sea: the crests I saw ravelled up by the wind into the air in arching whips and straps of glassy spray and higher broken into clouds of white and blown away. Under the curl shone a bright juice of beautiful green.

Gerard Manley Hopkins, journal entry, 16 August 1873.

Hopper, Groundswell.

Three latter-day excursions, two by sail, one by steamboat:

Frankie Ford's "Sea Cruise,” the greatest piece of New Orleans R&B performed by a white singer, came about when Ford’s vocal was dubbed over a Huey “Piano” Smith track. Smith had recorded the track with his then-lead vocalist, Bobby Marchan, but Smith's label Ace had asked Smith to redub the vocal, since Marchan wanted to go solo and the vocal allegedly wasn't up to scratch anyhow. So they got Ford, who provided a loopy, genius vocal, and added in some effects like a foghorn noise sped up to match the song’s key. Two decades later, the Clash would pillage this track for "Wrong 'Em Boyo." Everyone, now: Oooh-wee, ooh-wee, baby. Released as Ace 554; on tons of compilations, like Let's Have a Rock 'N Roll Party.

Billie Holiday’s "A Sailboat in the Moonlight” is state’s evidence that Holiday and Lester Young at their youthful peaks could turn any trifle into something masterful. Begin with a basic pop song written by one Carmen Lombardo, then watch as Holiday transforms the mediocre lyric, her phrasing making each line dazzle. Young, as her escort, offers an obbligato and then, given a few bars to cut loose, dances with her.

Recorded 15 June 1937, with Buck Clayton (t), Edmond Hall (cl); James Sherman (p); Freddy Green (g); Walter Page (b); Jo Jones (d). On Lady Day.

Brian Eno's "Julie With" is a more ominous pleasure cruise. The details are simple and precise--on a sailboat sitting becalmed on a silent ocean, the narrator watches his companion, Julie, lying face-up on the deck, her hand dipping into the sea. The music ebbs and flows, with keyboard washes, snaps of guitar, reaching no culmination, seeking none. But something seems off--the narrator isn’t disclosing the whole story. Julie could be thirty years old, or five; the narrator may be watching her absently, or he may have just killed her, and the reason “the still sea is darker than before” is because it’s mixing with blood. On 1977's Before and After Science.

The Ship? Great God, Where Is The Ship?

Roxy Music, Whirlwind.

Bessie Smith, Shipwreck Blues.

William and Versey Smith, When That Great Ship Went Down.

The Dixon Brothers, Down With the Old Canoe.

Woody Guthrie, The Sinking of the Reuben James.

Gordon Lightfoot, The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald.

The ocean cannot brook the slightest appearance of defiance and has remained the irreconcilable enemy of ships and men ever since ships and men had the unheard-of audacity to go afloat together in the face of his frown...If not always in the hot mood to smash, he is always stealthily ready for a drowning. The most amazing wonder of the deep is its unfathomable cruelty.

Joseph Conrad, The Mirror of the Sea.

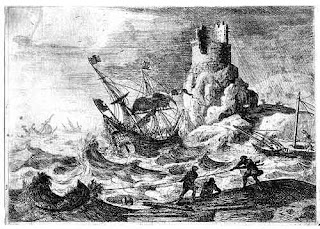

Lorrain, The Shipwreck, ca. 1640

Sea travel carries with it the chance of catastrophe, bestowing oblivion or exile through the encounter of a boat and a thirty-foot wave. Is there something especially unnerving about a shipwreck? A ship is our ambassador upon the ocean expanses--its demise shows how weak we truly are in the face of nature. Shipwrecks litter the cultural imagination, whether Odyessus' various troubles, or St. Paul, sailing from Judea to stand trial in Rome, whose boat wrecked on a lee shore near Valletta. Shakespeare's Tempest, in which a shipwreck ultimately restores the fortunes of Miranda and Prospero, or, of course, Robinson Crusoe.

Two days ago I was nearly lost in a Turkish ship of war owing to the ignorance of the captain & crew though the storm was not violent. Fletcher yelled after his wife, the Greeks called on all the saints, the Mussulmen on Alla, the Captain burst into tears & ran below deck telling us to call on God, the sails were split, the mainyard shivered, the wind blowing fresh, the night setting in, & all our chance was to make Corfu which is in possession of the French...I lay down on deck to wait the worst, I have learnt to philosophize on my travels & if I had not, complaint was useless. Luckily the wind abated & only drove us on the coast of Suli on the main land where we landed; but I shall not trust Turkish Sailors in future.

Lord Byron, letter to his mother, 12 November 1809.

"Whirlwind," in which Bryan Ferry stands on the deck in the face of the gale (and looking fabulous), is on Roxy Music's 1975 Siren.

Bessie Smith's "Shipwreck Blues" finds Smith singing about a shipwreck of the soul, a disaster that has only one form of deliverance; it's from one of her last sessions, in which she was backed by a quartet led by the pianist Clarence Williams. Recorded 11 June 1931 and released as Columbia 14663-D; on Empty Bed Blues.

Gericault, Raft of the Medusa.

At one time I saw Scott, standing on the weather rail of the poop, buried to his waist in green sea...over and over again the rail, from the fore-rigging to the main, was covered by a solid sheet of curling water which swept aft and high on the poop. At another time, Bowers and Campbell were standing upon the bridge, and the ship rolled sluggishly over until the lee combings of the main hatch were under the sea. They watched anxiously and slowly she righted herself, but "she won't do that often," said Bowers. As a rule if a ship gets that far over she goes down.

Apsley Cherry-Garrard, The Worst Journey In the World.

The Titanic, sea trials off Belfast, 1912.

Shine went on the deck, jumped overboard,

waved his ass, begin to swim.

With a thousand millionaires lookin' at him.

Then there is the most famous naval disaster of all, the RMS Titanic's 1912 sinking, immortalized by Leonardo DiCaprio and a host of folk and blues songs, the latter ranging from Blind Willie Johnson's "God Moves On the Water" to Ernest Stoneman's "The Titanic." Here are two more:

One of the first-ever recorded Titanic songs--versions had been circulating since 1914 or 1915-- is "When That Great Ship Went Down," a song emblematic of how many African-Americans viewed the Titanic disaster: since blacks had been barred from sailing on the Titanic, the sinking seemed like a bit of divine justice. (And of course, the Titanic sinking spawned a host of "Shine" (the legendary 'only black man on the Titanic') stories and toasts.)

William and Versey Smith were a husband-and-wife team of street musicians, possibly from the Carolinas (or Texas). They apparently only recorded four songs for Paramount, in Chicago. "Great Ship" was recorded in August 1927 and released as Paramount 12505B. On Anthology of American Folk Music or, cheaper, on Never Let the Same Bee Sting You Twice

And "Down With the Old Canoe," recorded a generation after the sinking, unsparingly states that the pride of man deserved a good dunking in the North Atlantic. The Dixon Brothers were Dorsey and Howard, millworkers from a millworker family in South Carolina, who learned guitar stylings from Jimmy Tarlton and who, by the mid-‘30s, had begun recording for Victor and playing radio shows. After World War II, the brothers went back to the mills, Howard dying on the job in 1960. Recorded in Charlotte, NC, on 25 January 1938; on Vol. 3 1937-38 (and eMusic).

A ship in harbor is safe, but that is not what ships are built for.

John A. Shedd, 1928.

Two more recent naval casualties:

The USS Reuben James was the first U.S. Navy ship sunk by the Germans, torpedoed on Halloween night 1941, a month or so before the U.S. entered the war (the ship had been escorting military supplies to the UK). Woody Guthrie, who spent the war as a cook and dishwasher in the merchant marine, recorded "The Sinking of the Reuben James" in 1944; on the Asch Recordings Vol. 1.

And finally, there's the SS Edmund Fitzgerald, the last great shipwreck of the 20th Century. Built in 1957-58 and named after the chairman of Northwest Mutual, the Fitzgerald was the largest ship on the Great Lakes. It was also an accident-prone ship--running aground, hitting lock walls, colliding with other vessels. In November 1975, out on Lake Superior, the ship was caught in an early winter storm and sank to the bottom of the lake, with 29 men aboard.

Gordon Lightfoot's ballad, written and recorded only months after the disaster, is on 1976's Summertime Dream.

Evacuations, Emigrations

Dunkirk, May 1940

Robert Wyatt, Shipbuilding.

The Pogues, Thousands Are Sailing.

Randy Newman, Sail Away.

Ships are the apparatus of desperate mass movements--of a population fleeing disaster, of an army invading or evacuating, of great waves of immigration.

Elvis Costello and Clive Langer wrote "Shipbuilding" during the Falklands War in 1982, which, in retrospect (or even at the time), seemed the last hurrah for the British Empire, and a fleeting hope for the revival of the British shipbuilding industry. Having gone to school in a town whose primary employers were military aircraft and submarine makers, I can attest to the odd, perverse hope that the threat of war will improve the local economy.

Langer had written a tune for Robert Wyatt but was unhappy with the lyric and asked Costello to re-write it; Costello then recorded it himself (with Chet Baker) for his 1983 album Punch the Clock. It's hard to say which is the better version, as both have their qualities (though Costello has admitted he regrets tinkering with Baker's trumpet solo during mixing). For me, the melancholy of Wyatt's vocal makes his take slightly more moving.

Wyatt's "Shipbuilding" was released on an EP, Rough Trade 115T, along with versions of Thelonious Monk's "'Round Midnight" and Eubie Blake's "Memories of You." On His Greatest Misses.

Years after I moved to New York, I finally made it out to Ellis Island one empty Saturday afternoon. My grandfather had emigrated from Cobh, Ireland, in the mid-1920s, and the family always had assumed he had come through there. So I wandered the halls, through the small rooms once used for medical exams and eye tests; feeling awed that my five-year-old grandfather had once walked there, a speck in a crowd, feeling guilty for having lived such a painless life in comparison. That Christmas, when I saw him and told him I had gone, he looked incredulous. “Ellis Island? Heh?” Turns out he had come into America via Poughkeepsie, or somewhere else he couldn’t even remember.

He died a few years ago: The Pogues' "Thousands Are Sailing," from 1988's If I Should Fall From Grace With God, is for him.

Normandy, June 1944.

"Sail Away" is Randy Newman's satire in which a slaveship captain lures a host of Africans on board for America, promising them earthly bliss, keeping the shackles out of sight. Greil Marcus' chapter on Newman in Mystery Train goes deep into the audacity of the song, which offers a grand delusive dream for a country founded on such dreams; it's a fantasy in which the great blot of slavery is wiped away with a tune that Stephen Foster could have written, all debts forgiven. On 1972's Sail Away.

Sailors On Shore

Fisherman's Group, What Shall We Do With a Drunken Sailor?

Billy Costello, Popeye the Sailor Man.

Hoagy Carmichael, Barnacle Bill the Sailor.

In 1822, an anonymous pamphlet was published in England entitled "A Statement of Certain Immoral Practices in H.M.'s Navy." The author was a naval officer, the pamphlet was sixty pages long, and its primary concern was the regular practice of bringing prostitutes onto ships in harbor.

It is frequently the case that men take two prostitutes on board at a time, so that sometimes there are more women then men on board. The lower deck is already much crowded by the ship's own company; you may figure...the intolerable confusion and filth...when an addition of as many women as men is made to this crowd. Men and women are turned by hundreds into one large compartment, and in sight and hearing of each other shamelessly and unblushingly couple like dogs.

Both sea captains and shorebound citizens have endlessly worried about the damage a group of sailors can cause when they reach the shore. While a bunch of young men trapped in confined quarters for months on end obviously needed some sort of release valve besides the usual sodomy, there were always complications. In the 17th and 18th Centuries, the problem for the British Navy, for example, was that so many sailors had been impressed into service that captains feared to let them go to land--hence the prostitute delivery service mentioned in the pamphlet above.

It was a problem even the pirates had to contend with--Ching Yih, a Chinese pirate captain who was the master of 800 junks in the early 19th Century, had an equally ambitious wife named Ching Yih Saoa. When Ching died, his wife took over the family piracy business. She had a few basic regulations about sailors, shore leave and women:

If any man goes privately on shore...he shall be taken and his ears perforated in the presence of the whole fleet; repeating the same act he shall suffer death.

Or: No person shall debauch at his pleasure captive women taken in the villages and open places and brought on board a junk, he must first request the ship's purser for permission...

Three songs about sailors on leave, whether drunk or wooing (or both):

"What Shall We Do With A Drunken Sailor?" is the last of the three shanties featured here from Peter Kennedy's LP Sea Songs. "The Fisherman's Group," who sang this version, were simply that, as Kennedy wrote: "The fishermen in Cornwall not only operated out of harbours, but also pushed their boats out from coves along the rocky shoreline. In the fifties they were entertaining holiday visitors with the more well-known songs and shanties in their 'local' at Cadgwith, near the Lizard. On the occasion that I recorded them in 1956, they were led by Bill Barber, from St Mary's in the Scilly Isles."

I'm Popeye the wife-beating man, 1935

Perhaps the most noted shore-bound sailor is Popeye, created by Elzie Segar in 1929 and who, in a few years' time, had become about as famous as a one-eyed grotesque sailor who lived in a menagerie of freaks could be.

"I'm Popeye the Sailor Man" was written by Sammy Lerner, and poaches from Gilbert and Sullivan's "Pirate King," from The Pirates of Penzance. It's performed here in a 1935 version by Billy Costello, an actor who was Popeye's first voice until he was sacked for allegedly just being a jerk. Jack Mercer, an animator, would take over as Popeye's voice for the next few decades.

Recorded 27 April 1935; on Vintage Children's Favorites.

In 1930, Victor Records assembled a Who's Who of jazz players--Bix Beiderbecke, Benny Goodman, Gene Krupa, Eddie Lang, Joe Venuti, Bubber Miley, Jimmy and Tommy Dorsey--to back Hoagy Carmichael for two sides. And one of the tracks, Victor insisted, would be the novelty number "Barnacle Bill the Sailor."

You can imagine the groans in the studio when the players heard this. Carmichael, hobbled with a hokey march tempo, shoved in two faster-paced sections to make room for two solos, a pairing that served as a changing of the guards: the first is one of Beiderbecke's last spotlights, the second is one of the young Goodman's first notable appearances.

The whole performance seems a hair's breadth away from obscenity, like a dirty joke whose punchline is being withheld; to add to the mayhem, Venuti loudly sings "Barnacle Bill the shithead" during the second chorus. Victor put the record out anyway. Recorded 21 May 1930; On Beat the Band to the Bar.

"Barnacle Bill" also has a long history as a rugby song. Full (and filthy, be warned) lyrics here.

With a Skull On Its Masthead

Lotte Lenya, Seeräuberjenny.

Lotte Lenya, Pirate Jenny.

Nina Simone, Pirate Jenny

Bob Dylan, When the Ship Comes In (demo).

Stephen Malkmus, The Hook.

Have you built your ship of death, O have you?

O build your ship of death, for you will need it.

D.H. Lawrence, The Ship of Death.

In no other area of transportation are the criminals so highly regarded. Maybe I'm wrong, perhaps there'll be a franchise of "Carjackers of St. Louis" movies in a few years. The romance of sea piracy (in reality a literally cut-throat business) seems an extension of how sea travel seems, in the general imagination, to grant liberties from life and the rules of civilization. Or maybe it's just the pirate outfits, which seem to come back into fashion every few decades.

Rather than try to sum up several hundred years' worth of pirate songs, I'll just choose one example.

man of wealth and taste

"Pirate Jenny" was written by Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill for Die Dreigroschenoper, their updating of John Gay's Beggar's Opera. Of all the songs in Threepenny Opera, "Pirate Jenny" is a cuckoo's egg--it stands outside the plot, has no real significance to anything else that occurs; it can be used in almost any scene, and even lacks any connection to a specific character. At first the song was intended for the lead female role, Polly, to be sung at her wedding, but in G.W. Pabst's 1931 film version of Threepenny Opera, Lotte Lenya, playing Jenny Diver, took over the song, and it was hers forever afterward.

"Pirate Jenny" is a remorseless fantasy of blood and revenge, sung by one of society's discards. With its utter callousness toward human life, and the delight that the singer takes in imagining her co-workers and customers massacred and her town burned to the ground, the song, more than anything else in the opera, seems horrifyingly prescient. The history of the past 70 years has been, in part, a list of damage wrought by such people, with the Virginia Tech massacre as but one recent example.

In "Pirate Jenny," the pirates are off-stage--they exist merely as avenging dark angels, forces from beyond who come in to liberate the singer, who is an utter nonentity in her world. It's the reverse of the typical sea fantasy, in which someone trapped on land wishes to take to the seas to escape: "Pirate Jenny" is the song of someone who wishes the seas, in all their violence and disunion, would come to them.

Here are two versions of Lenya's performance--"Seerauber-Jenny," was recorded in Berlin in 1930 as part of several recordings made with the original cast. And Lenya's "Pirate Jenny" comes from Marc Blitzstein's 1954 English adaptation, which finally established Threepenny Opera as a standard in the U.S. (A '30s version had flopped.) Recorded April 1954; on Original Soundtrack.

Anne Bonny, who told her husband, the pirate Calico Jack, at his trial: "If you had fought like a man, there would be no need to hang like a dog."

Nina Simone's version of "Pirate Jenny," from 1964, resets the stage. The singer is now not just a maid in a seaside village, she is a black woman in a "crummy Southern town," and the retribution she imagines and demands is nothing less than an Old Testament-style annihilation of a corrupt, bigoted culture. It's an astonishing performance, in which Simone seems to live out an entire bloody lifetime in the course of a few minutes. Recorded live at Carnegie Hall on 21 March 1964. On Best of Nina Simone.

And Bob Dylan's "When the Ship Comes In" continues the reworking of "Pirate Jenny" into an ode to divine justice: here, with even the rocks and fish dancing in celebration, the pirate crew informs the people of the town that their reign is over, then all of the corrupt are swept out by the tide. (Dylan's song retains an element of base revenge, however, as Joan Baez recalled Dylan writing the song in a hot rage after being treated rudely by a hotel clerk.)

This is a demo recorded for Dylan's publishing company, Witmark, taped in August-September 1963; released on Bootleg Series Vols. 1-3. The official take is on Times They Are A-Changin'.

Finally, as an epilogue, Stephen Malkmus offers piracy in its more basic state--just your average kidnapping, maiming, murder. "And if I spare your life it's because the tide is leaving." On 2001's Stephen Malkmus.

Rolling On the River

Frank Trumbauer with Bix Beiderbecke, Riverboat Shuffle.

Jelly Roll Morton and His Red Hot Peppers, Steamboat Stomp.

Clara Smith, Steamboat Man Blues.

Delmore Brothers, Steamboat Bill Boogie.

The Band and Emmylou Harris, Evangeline.

Jim took up some of the top planks of the raft and built a snug wigwam to get under in blazing weather and rainy, and to keep the things dry. Jim made a floor for the wigwam, and raised it a foot or more above the level of the raft, so now the blankets and all the traps was out of reach of steamboat waves...We fixed up a short forked stick to hang the old lantern on, because we must always light the lantern whenever we see a steamboat coming down-stream, to keep from getting run over; but we wouldn't have to light it for up-stream boats unless we see we was in what they call a "crossing"; for the river was pretty high yet, very low banks being still a little under water; so up-bound boats didn't always run the channel, but hunted easy water.

This second night we run between seven and eight hours, with a current that was making over four mile an hour. We catched fish and talked, and we took a swim now and then to keep off sleepiness. It was kind of solemn, drifting down the big, still river, laying on our backs looking up at the stars, and we didn't ever feel like talking loud, and it warn't often that we laughed -- only a little kind of a low chuckle. We had mighty good weather as a general thing, and nothing ever happened to us at all -- that night, nor the next, nor the next.

Mark Twain, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.

River travel is the domestic sphere of sailing, in which the river and its vessels serve as the lifeblood (or antibodies) of a city. That said, river travel has its own mysteries--rivers are often used as a means of escape, a place to throw bodies, as the avenue of smugglers and fugitives.

Here are a few river songs, mainly focusing on the mighty Mississippi:

"Riverboat Shuffle" features the genius of Frank Trumbauer on C-melody saxophone and Bix Beiderbecke on trumpet, along with Bill Rank (tb), Don Murray (cl), Eddie Lang (g). Recorded in New York on 9 May 1927; on Singin' The Blues.

Jelly Roll Morton's "Steamboat Stomp" was recorded with Barney Bigard and Darnell Howard (cl), Kid Ory (tb), Johnny St. Cyr (banjo), John Linsday (bass), Andrew Hillaire (d). Recorded in Chicago on 21 September 1926; on Birth of the Hot.

Clara Smith, considered Bessie Smith's greatest rival in terms of '20s blues records, cut "Steamboat Man Blues" in Chicago. Recorded 23 May 1928 and released as Columbia 14344. On Complete Recorded Works Vol. 5 and eMusic.

The Delmore Brothers' "Steamboat Bill Boogie" finds the brothers at the end of the road, when they were making rock & roll records in all but name. Recorded in Cincinnati on 21-22 October 1951 and released as King 1023; on Freight Train Boogie.

Cincinnati waterfront, 1865.

"Evangeline," an Acadian riverboat saga, was one of the last songs recorded by The Band, who, with guest star Emmylou Harris, performed the song on an MGM soundstage specifically for Martin Scorsese's film, after the Band's farewell concert had been filmed. On The Last Waltz. (Around the same time, Harris recorded another, more country solo version, which became the title track of her out-of-print 1981 album--it can be heard on this site.)

Sail On

becalmed ship, Bering Strait

The Revels, The Leaving of Liverpool.

Richard Thompson, Mingulay Boat Song.

The Beach Boys, Sail On, Sailor.

After the storm

the other boats didn't

hesitate--they spun out

from the rickety pier, the men

bent to the nets or turning

the weedy winches.

Surely the sea

is the most beautiful face

in our universe, but

you won't find a fisherman

who will say so;

what they say is,

See you later.

Mary Oliver, The Waves.

George Eastman, on board S.S. Gallia, 1890.

Let's end with some leavings and homecomings:

"The Leaving of Liverpool" likely hails from the mid-19th Century--it can be traced back to 1885, when a seaman named Dick Maitland claimed he had heard a Liverpool-born sailor singing it in the foc's'le of a ship called the General Knox. Maitland taught it to the folk- song collector W.M. Doerflinger, who published the song in 1951. On The Revels' Homeward Bound, from 2002.

The first busy day of a homeward passage was sinking into the dull peace of resumed routine. Aft, on the high poop, Mr Baker walked shuffling and grunted to himself in the pauses of his thoughts. Forward, the look-out man, erect between the flukes of the two anchors, hummed an endless tune, keeping his eyes fixed dutifully ahead in a vacant stare. A multitude of stars coming out into the clear night peopled the emptiness of the sky. They glittered, as if alive above the sea; they surrounded the running ship on all sides; more intense than the eyes of a staring crowd, and as inscrutable as the souls of men.

The passage had begun, and the ship, a fragment detached from the earth, went on lonely and swift like a small planet.

Joseph Conrad, The Nigger of the 'Narcissus'.

Mingulay is one of the Bishop's Isles in the Outer Hebrides, so when a Scottish sailor was homebound, seeing Mingulay would often be the first indication they were reaching land. "Mingulay Boat Song," however, isn't really a traditional shantey--it was written by Hugh S. Roberton, the founder of the Glasgow Orpheus Choir, in 1938, more than two decades after Mingulay had been abandoned by its inhabitants.

Richard Thompson's version is from 2006's Rogue's Gallery.

And the Beach Boys' "Sail On, Sailor" is from 1973's Holland. Dedicated to Tom Birnbacher.

Many anecdotes, information, photos, quotes, etc. are derived from three phenomenal anthologies: The Oxford Book of the Sea, edited by Jonathan Raban; The Norton Book of the Sea, ed. John O. Coote; and The Book of the Sea, ed. A.C. Spectorsky. Spiritual guidance: Yacht Rock.

No comments:

Post a Comment