"Clarence and Alonzo," photo taken by Wilbur or Orville Wright, back of the Wright Cycle Co. in Dayton, Ohio, ca. 1900 (from Shorpy)

1900

Scott Joplin and Arthur Marshall, Swipesy Cakewalk.

Vess Ossman, Ethiopian Mardi Gras.

Arthur Collins, The Mick Who Threw The Brick.

Dear Evelyn: Your letter was waiting for me when I came home, but was not the less interesting because I had seen you in the meantime. We usually say more in a letter than we do in conversation, the reason being that, in a letter, we feel that we are shielded from the indifference or enthusiasm which our remarks may meet with or arouse. We commit our thoughts, as it were, to the winds. Whereas, in conversation, we are constantly watching or noting the effect of what we are saying, and, when the relations are intimate, we shrink from being taken too seriously on one hand, and, on the other not seriously enough--

But people no longer write letters. Lacking the leisure and, for the most part, the ability, they dictate dispatches, and scribble messages...In these days, we have not the artlessness nor the freedom of our forbears. We know too much about ourselves. Constraint covers us like a curtain. Not being very sure of our own feelings, we are in a fog about the feelings of others. And it really is too bad that it should be so.

Joel Chandler Harris, letter to his son, 5 April 1900.

Louisville, Kentucky, 1900

Our story could start anywhere, so it might as well begin here, in Sedalia, Missouri, on some lost evening at the rag end of the 19th Century. Sedalia is a frontier town, and still young--it began as a Union military post at the start of the war, and by 1899 some 15,000 people have come to live here, to work on the railroads, in the restaurants, in the seed and harness stores, and in the bordellos and honky tonks.

For while Sedalia by day is a quiet little plains town, with just a dirt road, lined by wooden sidewalks shaded by corrugated iron awnings, to serve as its Main Street, at night it gets wild. Gamblers, prostitutes, pimps, cardsharps, hustlers of all stripes and even the occasional respectable citizen flood Main Street, weaving in and out of the sporting houses and the taverns. One of the latter, the most popular, is the Maple Leaf Club, where each night a neatly-dressed, somber-looking man plays "jig piano" amidst the smoke and noise.

This is Scott Joplin, who would much rather be in a conservatory somewhere. Still, as he works his intricacies on the upright piano while choruses are howled by gamblers and drinkers all around the room ("You been a good ol' wagon but you done broke down!" "Oh! Mr. Johnson turn me loose!"), Joplin lets the trace of a smile escape.

Hammershøi, Sunbeams or Sunshine, Dust Motes Dancing in the Sunbeams.

Rags were played in Sedalia before Scott Joplin settled there, but he got to making them really go.

Arthur Marshall.

Joplin had come to Sedalia around 1895, looking for some steady work and using the local college as a means to improve his composition skills. In the previous decade, Joplin had struggled to bring something to light--he had toured the Midwest and Northeast in minstrel troupes and ramshackle vocal groups, trying to get his own compositions published, with meager success.

Things began to coalesce when Joplin went to the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893. The Exposition was something like a coming-out party for the upcoming century--everyone from Thomas Edison to Nikola Tesla came, and everything from Cracker Jack to the Ferris Wheel to the hootchy-koo dance debuted. There Joplin met and likely played with the Chicago ragtime pianists Johnny Seymour and "Plunk" Henry Johnson.

In Johnson, Joplin found an echo of his own emerging voice. Joplin, from Texarkana, was the son of a slave; Johnson, who came from the Mississippi Valley, likely was born a slave. Both had started out as banjo players. One imagines the two in an idle hour playing a duet: Johnson on banjo, Joplin on piano. Or Johnson offering some lessons on the piano, showing that the basic idea of banjo syncopation, of hitting on the off beats, can be simply transferred to the piano keys. Jus' ragging it up, he says.

In 1899, when Joplin publishes "Maple Leaf Rag," named after his one-time employer, the world is finally ready for him. "Maple Leaf Rag" sells 75,000 copies in six months (sheet music, not records) and Joplin's publisher, John Stark, pushes him for as many new compositions as he can get out.

In the next year comes "Swipesy Cakewalk," a Joplin collaboration with a young Sedalian composer named Arthur Marshall, who is only nineteen years old. When Joplin first arrived in Sedalia, he had been a boarder in Marshall's mother's house, and came to regard the younger man as his protégé. Marshall, who desperately wanted Joplin to get him into the Maple Leaf Club, managed to learn composition as well.

"Swipesy" is mostly Marshall's work. Like most ragtime pieces, it has four sections, with the opening one featuring an oom-pah bass pattern, aligning it with brass band music, while the second section is less complex, more like the cakewalk that the title suggests. The third (trio) section is likely Joplin's major contribution to the piece, with an elegantly structured melody. The final section, which goes back to the original key of B flat major, lets the pianist do a bit of stride playing. (More from Bill Edwards' analysis.)

This recording of "Swipesy Cakewalk"is arranged as a duet of piano and banjo, and it seems fitting to have the two prodigies of ragtime together in syncopated partnership. Recorded by Max Morath (p) and Jim Tyler (b) in 1972, on the Vanguard LP Max Morath Plays the Best of Scott Joplin.

Using recordings to get a sense of early 20th Century popular music has its perils. For one thing, black musicians (and rural white musicians) were all but ignored until 1920, so that the surviving records of the first two decades offer a skewed picture in which brass bands, banjoists, whistlers, sentimentalists, mediocre classical song recitals and belabored jokes seem to be the dominant musical forms.

So while the legendary trumpet player Buddy Bolden, one of the pioneers of jazz, was never recorded and even Joplin is only available to us through a handful of piano rolls, the likes of the banjoist Vess Ossman are omnipresent. David Foster Wallace, writing about the prolific John Updike, cracked that Updike had never had an unpublished thought, and you could use a similar riff with Ossman, who is everywhere on shellac and cylinder, backing everyone from "coon shouters" to parlor pianists and even being shoehorned into orchestras.

Ensor, Death and the Masks.

Sylvester Ossman, born in Hudson, NY, in 1868, began playing the banjo at age twelve and soon set upon a demanding work regimen--he claimed to practice at least four hours a day, and sometimes ten. It paid off. By 1900, he was playing for the Prince of Wales, the future Edward VII (Bertie was a banjo enthusiast), and was recording like a fiend. Ossman began making brown wax two-minute cylinders in 1893 and kept on, cutting the first record with "ragtime" in the title (1897's "Ragtime Medley"), and he didn't start to flag until the First World War. His legacy is thousands (literally) of records, many of which have survived, making him impossible to avoid in any survey.

Like most successful studio musicians, Ossman worked quickly, proficiently, with no drama, and evidently he was always available. It also helped that the primitive standards of early recording favored instruments with high treble and strong projection--fiddles, clarinets, cornets, banjos. His solo oeuvre consists, on the whole, of "strange little time-capsule set pieces of early white ragtime, stiffly strummed and picked...his facility was impressive, but he had little real idea of vernacular time and seemed occasionally like a duck out of water" (Allen Lowe). Ossman, at his best, has a hard, relentless force to his playing, in which speed and volume take precedence over rhythmic sense.

So here's one of many: Ossman's take on "Ethiopian Mardi Gras," written by Maurice Levi, recorded in New York sometime in early 1900. The pianist Frank Banta accompanied him. Released as Zon-O-Phone 9188; on Ragtime to Jazz Vol. 4.

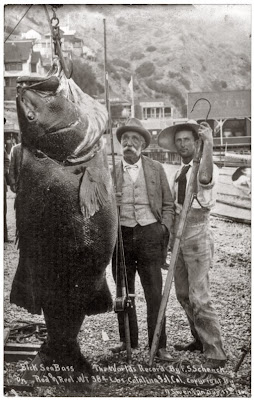

Alleged 384-lb black sea bass, caught off Catalina Island, 17 August 1900.

One of Ossman's regular accompanists was the singer Arthur Collins, who first appeared on record in 1898 and whose first major hit was "All Coons Look Alike to Me." Collins, while he had been a professional singer since his childhood, went respectable upon his marriage in 1895, learning bookkeeping and typewriting. After six months of work at a cigar factory, however, his arm went lame, and soon enough Collins was back in show business for life. Like Ossman, he seems to have recorded every popular song composed between 1900 and 1915.

"The Mick Who Threw the Brick" is, according to a 1901 issue of Dominicana: A Magazine of Catholic Literature, "a comic Irish song full of drollery." The song marked the reunion of Arthur Blake and Charles Lawlor, who had written "Sidewalks of New York" together a few years before, though "Mick" has none of the latter's charm. Collins' version was recorded sometime in 1900 and released as Edison Concert cylinder B-522 (he cut another version for Berliner around the same time). Available here.

1901

Gertrude Kasebier, Portrait--Miss N. (Evelyn Nesbit), 1901-02.

The Sousa Band (with Arthur Pryor), Pasquinade.

Steve Porter, Carrie Nation in Kansas.

Columbia Quartette, Way Down Yonder in the Cornfield.

Len Spencer, You've Been a Good Old Wagon.

Benjamin Harney, You've Been a Good Old Wagon.

It is salutary to realise the fundamental isolation of the individual mind. We have no certain knowledge of any consciousness but our own. We can only know the world through our own personality. Because the behaviour of others is similar to our own, we surmise that they are like us; it is a shock to discover that they are not. As I grow older I am more and more amazed to discover how great are the differences between one man and another. I am not far from believing that everyone is unique.

W. Somerset Maugham, notebook, 1901.

Kubin, The Lady on the Horse (1900-01).

The Sousa Band, who Joplin had heard perform at the Columbian Exposition, was a brass orchestra led by John Philip Sousa, who passionately hated the concept of recording, considering "mechanical music" a menace that would vitiate live performance, and even testifying to Congress that he had never been in a record company office. He didn't mind getting checks from record companies, however, and let his band cut as many tracks as they could.

So the job of conducting Sousa band recording dates often fell to his star trombonist Arthur Pryor. Pryor had a taste for rags and cakewalks and once in a while, in a recording, he would hint at something far beyond the ken of a typical brass band--like 1902's "Trombone Sneeze," in which Pryor has a brief, possibly improvised solo using "bent" notes, along with a call-and-response section with the rest of the band.

When Pryor formed his own band the following year, he kept innovating, both in studio arrangements (Pryor pushed for simpler, cleaner takes and even managed to get a halfway-decent bass sound) and in his taste for the hippest new material, like "St. Louis Rag," which he cut in 1904. It's enough to make you wish to nudge Pryor a few decades ahead in time, to hear what he would have done in the swing era, for instance.

The White House kitchen, 1901

"Pasquinade" was originally a piano piece (op. 59) written by Louis Moreau Gottschalk. Gottschalk was a great, if now forgotten, transitional figure in American music, a half-Jewish Creole composer and pianist, and a "purveyor of vernacular influences translated into middle-class expression, a virtuoso of Lisztian technique who wrote compositions indebted to the dance rhythms of his native New Orleans" (Lowe). Gottschalk was also one of the first internationally renowned American musicians: he toured Europe and South America, and he died in 1869 in Rio, after collapsing on stage while playing his piece "Tremolo."

Sousa's Band, led by Pryor, manages to preserve the lightness and flair of Gottschalk's piece and masters its intricate rhythms fairly effortlessly; the track was recorded in Philadelphia on 7 June 1901, and issued as Victor 3438.

"Carrie Nation in Kansas" is primitive musical satire, mocking the notorious temperance advocate (Nation would sometimes back her teetotal convictions with an axe, smashing up saloons accompanied by a pack of hymn-singers). Nation would help lead the push for the 18th Amendment that banned alcohol manufacture, sales and distribution, thus inspiring speakeasies and organized crime, and so also, indirectly, helping make jazz a popular music. It just goes to show that you never know what your consequences are going to be.

Recorded by Steve Porter, ca. August 1901 and released as Columbia 31577; find here.

As David Wondrich writes in his pugnacious Stomp and Swerve: American Music Gets Hot, one major historical achievement of the cylinder era of popular music was that it captured, almost entirely, "the whole spectrum of Reconstruction-era minstrelsy," from weepy "plantation" songs to bottom-barrel vile racist garbage.

The Columbia Quartette's "Way Down Yonder in the Cornfield" is somewhere between the two extremes. It is a quartet of white singers (their names lost to history, though one might have been George "Honey Boy" Evans, a popular minstrel) singing horrific lyrics, but there's also, if you can stomach the bilge, a sense of innovation and freedom (from earlier, European modes of performance) in their singing, especially when the quartet does a "banjo" breakdown late in the performance.

Recorded ca. 1901, released as Columbia Moulded Brown Wax Cylinder 9029; find in this archive.

Len Spencer, in photographs, looks more like a classic anarchist than a recording star. His massive head, which appears hewn out of granite, is topped by a crest of thick black hair, so that one imagines his grim face hanging like a lantern over a filthy desk covered with scribbled manifestos. On record, however, Len Spencer just desperately wanted to sound like a black man.

Of all the cylinder-era minstrels, Spencer is perhaps the most shameless and offensive, and yet in his performances there is also a vulgar power and perhaps, deep in the muck, even a measure of respect for his sources. His finest record is his take on "You've Been a Good Old Wagon But You Done Broke Down," in which Spencer's singing is matched by some vigorous piano runs by some unknown player.

The story circles inward, like the whorls of a seashell. "You've Been a Good Old Wagon"'s composer, ragtime pioneer Benjamin Harney, was thought to be black by many of his contemporaries. The pianist Eubie Blake, interviewed by Alec Wilder in the early '70s, said of Harney, "He's dead, and all of his people must be. Do you know that Ben Harney was a Negro?" Convinced, Wilder, in his American Popular Song, calls Harney "one of the best Negro writers of the late nineteenth century." The Harney family, on its genealogical website, makes an exhausting case, however, that Harney was a white man born to white parents.

Included in the list above is the only vocal Harney ever recorded, of "Good Old Wagon," made for the archivist Robert Winslow Gordon in Philadelphia on 9 September 1925 (Gordon Cylinder G24). You certainly can hear where Eubie Blake got his ideas from.

So, to sum up, Spencer's recording is that of a white man trying to sound black who is singing a song written by a white man who even black folks thought was black. You could be facile and call it the story of America, or at least one of its stories.

Spencer's "Good Old Wagon" was recorded in either 1901 or 1902 and released as Lambert 989; many of Spencer's surviving recordings, including this one (and two reenactments of scenes from Uncle Tom's Cabin, which could be the most horrendous things ever recorded--I haven't had the heart to listen), have been archived here.

Next: The President is Seven Years Old.

Sources: Rudi Blesh and Harriet Janis, They All Played Ragtime; Wondrich, Stomp and Swerve; Tim Gracyk, Popular American Recording Pioneers; Lowe, American Pop and That Devilin' Tune.

No comments:

Post a Comment