Eck Robertson and Henry C. Gilliland, Arkansas Traveler.

Eck Robertson, Sallie Gooden.

Eck Robertson, Ragtime Annie.

The talent manager at the Victor Talking Machine Co. sits in the office of his colleague who runs publishing. He often comes in here when his colleague is out, mainly to hide from his own prospects. He drinks a cup of coffee as he sits in the spare chair and looks out at the chalky June morning over New York.

His secretary, all bobbed hair and ankle-strapped shoes, pokes in to tell him the first tryouts of the day are in his office. They're a real pair, she says. You've gotta see 'em. Sure I've got to, he says. They're from Texas, so they say, she adds. Wonderful, he says.

He watches her go, which is always a highlight of his day, and wonders again why he got into this line. The desperate who stream into his office, all wanting to make records. The six-rabbi singing group. The ashy man who could play ragtime piano with his toes. The pair of old women who sounded like lowing cattle. The man who claimed his dog could howl an aria from La Bohème (the dog, likely imaginary, also could count, he said). The Croat who struck his child across the face with a riding crop when the kid got nerves and botched a note.

He's stalled enough, so he gets up and walks to his office. He takes a piece of paper off his secretary's desk, just a typed list of distributor names, to use as part of one of his standard ploys. He strides through the doorway, staring at the paper as though it was his last will and testament, and slams himself down behind his desk. The two men jump to their feet as he walks in. He doesn't look at them. He keeps staring at the paper, now just blurring the words together by squinting. Sometimes they can't take the tension and just bolt out of the office: that's always nice. He hears rheumy breathing, the rustle and clank as they shift their weight. At last he looks up.

Each holds a fiddle case, each is in costume. One's in pearl-studded cowboy gear with some sort of lurid purple silk shirt, the other's in a full-dress Confederate Army uniform. He really is a Civil War veteran, it turns out. His name's Henry Gilliland. Later, a recording engineer makes small talk with him, asks him what he thinks of New York. It's fine enough, sir, Gilliland says, but you should've seen Atlanta before your General Sherman got done with it.

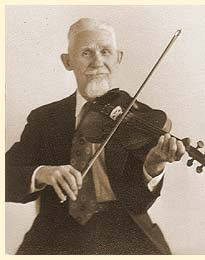

The other fiddler, Eck Robertson, is wiry, speaks with the rapid patter of a confidence man. He's a stage pro, he says, and so's his wife, and so's his children. The manager worries that this brood is waiting for a cue to pour into his office, but no, it's just Eck and Henry up in New York, just wanting to make a record.

So the manager folds his arms, leans back, makes his choice. He stares at Robertson and says: "Young man, get your fiddle out and start off on a tune. I can tell that quick (a sharp finger snap) whether I could use you or not." The Texan unpacks his fiddle, tunes it by plucking two strings and twisting a knob, brings his bow down in an arc.

Halfway through "Sallie Gooden," as Robertson reels out line after line at breakneck speed, to the point where his fingers seem to have become fluid, the scout just smiles, throws up his hands, surrenders. "By Ned, that's fine!" he laughs. "Come back tomorrow at nine o'clock and we'll make a test record."

Alexander Campbell "Eck" Robertson was born in 1887 and grew up near Amarillo, Texas. He was the son and grandson of fiddlers (his father had put down the bow to become a preacher) and by age 16 he was playing fiddle in medicine shows that worked Indian territories. He married a childhood friend, Jeanetta Levy, and performed with her on stage; when each of their 10 children grew old enough they joined the troupe. When he wasn't on the road, Robertson worked as a piano tuner and played in fiddling contests throughout Texas (he was a brutal competitor--throwing his bow in the air, catching it and swooping down to the strings, not having missed a beat, or sticking a wooden match under one of his strings so he could bow three strings at once).

Robertson had met Gilliland at a Confederate veteran's reunion in Richmond (though they may have crossed paths before) and the two decided they wanted to make a record. A friend of Gilliland's in New York who did legal work for Victor got them the audition.

At the Victor sessions, Robertson and Gilliland first cut a few fiddle duets, including "Arkansas Traveler," and then Robertson returned alone (it seems pretty clear that Victor regarded him as the greater talent) the following day to cut tracks backed by a session pianist as well as make two solo fiddle recordings, "Sallie Gooden" and "Ragtime Annie."

"Sallie Gooden," the song that won Robertson his record contract and that would be his first-issued Victor disc, is Robertson performing at a master level. The song "Sallie Gooden" typically has two melodic strains--Robertson plays 13 different variations in the course of three minutes. This is hard Texas hillbilly barn-dance jazz, grooved onto wax. "He sawed off everything from syncopated runs and blue notes to single-string/double-string harmonies and clusters of quicksilver grace notes with a horn-like timbre" (Bill Friskics-Warren, in Heartaches By the Number).

For a while some music historians believed "Ragtime Annie" was derived from a Native American dance tune and was as old as the United States, but more recently a consensus has pegged the song as a modern piece, ca. 1900, possibly derived from a ragtime piano tune "Raggedy Ann Rag."

From Ceolas: There is often some confusion among fiddlers whether to play the tune in two or three parts, and both are correct depending on regional taste. Eck Robertson's version was in three parts (the third part changes key to G major) as are many older Southwest versions, and some insist this form was once more common that the two-part version often heard in more recent times...Little Dixie, Missouri, fiddler Howard Marshall says that local speculation is that the third part was inserted to relieve a square dance fiddler from the stress of keeping the main part of the tune going through a long set.

Denouements: Gilliland died two years later; Robertson, despite setting the template for generations of country musicians, recorded only sporadically in the years afterward, though he lived until 1975; Victor merged with RCA in 1929 and became one of the major country labels of the 20th Century, home of everyone from Dolly Parton to Hank Snow to Willie Nelson.

Discography: "Arkansas Traveler," recorded on 30 June 1922, and "Gooden" (1 July 1922) were released as the two sides of Victor 18956 (not until spring 1923, as Victor had no clue how to sell records to rural Southern markets); "Annie," recorded on 1 July 1922, was released as Victor 19149; in this archive, this one and this one. They're all collected on Old-Time Texas Fiddler.

Disclaimer: Were these really the first-ever country records? No. Len Spencer and Charles D'Almaine cut "Arkansas Traveler" as early as 1902, Don Richardson started cutting solo fiddle records in 1914 (including "Arkansas Traveler" in 1916), and even the Victor Military Band did a 1920 version of the fiddler staple "Soldier's Joy." The main difference was that these were studio pros, based mainly in New York (Richardson had been born in North Carolina, but moved to NYC in 1910 and worked for a decade with a variety of studio orchestras). So perhaps Robertson and Gilliland had a rural mojo that the earlier players lacked, perhaps not. Nick Tosches has argued these pre-Robertson records were often "stylized adulterations of a music that the record companies felt was not commercial in its real state...not too different from the way record companies treated black music before 1920."

Descriptions (sources): The Encyclopedia Of Country Music; Bill Malone, liner notes to The Smithsonian Collection of Classic Country Music LP set; Allen Lowe, American Pop; David Cantwell and Bill Friskics-Warren, Heartaches By the Number; Tosches, Country; this site reproduces the liner notes of County LP 202, Eck Robertson, Famous Cowboy Fiddler. Everything in the above post is true or ought to be.

No comments:

Post a Comment