The Kinks, Celluloid Heroes.

Velvet Glove, Movie Star.

Prince, Movie Star.

The picture pride of Hollywood.

Too many fall from great and good

For you to doubt the likelihood.

Die early and avoid the fate.

Or if predestined to die late,

Make up your mind to die in state.

Robert Frost, "Provide, Provide."

Singers and songwriters, despite their arrogance, talents and inspired delusions, still live in the shadow of movie stars. When you think of the great rock stars of the 20th Century--Elvis, Lennon, Hendrix, Jagger, Springsteen--you realize they don't hold a candle to Greta Garbo or Humphrey Bogart. There is a hierarchy, and most musicians respect it. Yes, there has always been a bleed-through with pop music and film--such as in the '30s and '40s, when many film stars also cut records, or today, when any remotely talented twentysomething actress with remotely adequate vocals is in a band. But at day's end, the musicians are sitting anonymously in the dark, in love, as we are, with the faces shining above them on the screen.

Songs about movie stars tend toward the sentimental and the nostalgic, offering praise or eulogies for a film star loved in youth (or only yesterday); they seek to recapture the way the image of an actor's face, projected some thirty feet high and seventy feet wide, while we stare at it in darkness, can upturn the dry drudgeries of our lives and propel us into some greater dream. "I was watching a movie with a friend," Neil Young sang in "A Man Needs a Maid." "I fell in love with the actress--she was playing a part I could understand." (He was singing about when he saw Diary of a Mad Housewife, and its lead actress Carrie Snodgress, who he later lived with and had a kid with--Neil went one up on most of us). Many of these songs cross the boundary line into worship, for in recalling the power that movie stars have held over us, we tend to remember ourselves at a higher state of being, however delusive it was.

Take the Kinks' "Celluloid Heroes," in which Ray Davies devolves into a wistful child in the face of some lost Hollywood of his imagination. Even George Sanders, an actor almost forgotten today, leaves him drunk with admiration. (On 1972's Everybody's In Show Biz.) Or the gloriously overwrought "Movie Star," by the lost '70s band Velvet Glove (or New Velvet Glove), in which a starlet making it in Hollywood seems akin to one of the penitents in Dante's purgatory being allowed at last to sail up to the lowest sphere of the heavens.

Sometimes the fantasies are more base--we want to be movie stars because of the things we could get away with. Prince's "Movie Star," an outtake from 1987, has Prince trying on being a movie star like a fresh new set of clothes (for a brief moment, up until the night Under the Cherry Moon opened, Prince nearly was a movie star, but this track is more spoof than aspiration). (On the now out-of-print outtake collection Crystal Ball.)

Today's Divine Surprise (1912-1929)

Vernon Dalhart, There's a New Star in Heaven Tonight (Rudolph Valentino).

Vic Chesnutt, Lillian Gish.

Cleaners From Venus, Clara Bow.

Lou Reed, City Lights.

Curtis Eller's American Circus, Buster Keaton.

Nick Lowe, Marie Provost.

Bing Crosby and Paul Whiteman, If I Had a Talking Picture of You.

"Universal City, California, Only Municipality in World in Which Entire Population Consists of ‘Movie’ Stars, Swept By a ‘Votes for Women’ Crusade." Earliest printed appearance of the phrase "movie star," according to the Oxford English Dictionary: headline in Lima (Ohio) Daily News, 16 May 1913.

In the beginning, for some fifteen years after the Lumière Brothers first projected films for a paying audience, actors typically weren't credited on their movies. Studio heads believed that if actors became known by name among the general public, the actors could leverage their popularity for salary increases and would soon be bossing around directors and producers. This theory proved to be absolutely right, but the studios had no choice. The public demanded to know who "the Biograph girl" really was, and eventually producers realized they could make good money off the audience's desperate need to see their stars in whatever dreary picture the actors appeared.

Moviegoers, Washington DC, 1939

Greil Marcus, in Mystery Train, wrote about the first generation of rock & roll musicians: I feel a sense of awe at how fine their music was. I can only marvel at their arrogance, their humor, their delight. They were so sure of themselves. They sang as if they knew they were destined to survive not only a few weeks on the charts but to make history; to displace the dreary events of the fifties in the memories of those who heard their records; and to anchor a music that twenty years later [this was written in 1974] would be struggling to keep the promises they made.

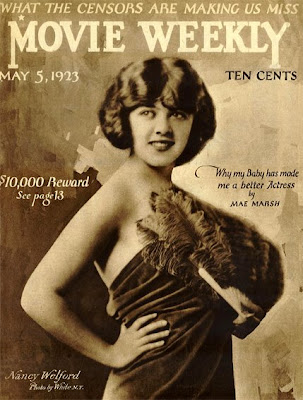

Much of that can be said equally about the first generation of movie stars--Mary Pickford, Douglas Fairbanks Sr., Blanche Sweet, William S. Hart, Mae Marsh, Rudolph Valentino, Harold Lloyd, Barbara Bedford, and the brilliant clowns Chaplin and Keaton. Along with directors like Griffith, DeMille, Maurice Tourneur, Louis Feuillade and Victor Sjostrom, and cameramen like Billy Bitzer, they created the movies. Imagine if a group of some fifty people, over the course of a decade, had created the English language--much of its vocabulary, its idioms, its rhyme schemes, its tenses, its literature. That's essentially what these people did.

She is madonna in an art

As wild and young as her sweet eyes:

A frail dew flower from this hot lamp

That is today's divine surprise.

Vachel Lindsay, "Mae Marsh, Motion-Picture Actress."

Mae Marsh contemplates the void

People did not know what to make of a girl who looked like that. Why employ one who without qualification of wealth, rank, fashion, or ability (so far as they knew) made them feel ordinary? Behind those large dark eyes and silent lips, what went on? It worried Boney Blayds & Co., and the more wholesale firms of commerce. The lurid professions—film-super, or mannequin—did not occur to one, of self-deprecating nature, born in Putney.

John Galsworthy, The White Monkey.

The price exacted for their own brief fame, and for begetting the golden age of Hollywood and modern celebrity, was that the founding generation's own lights quickly dimmed. In terms of popular music, they are all but anonymous--only a few contemporary songs about silent film stars were written, most notably "There's a New Star in Heaven Tonight," dashed out to commemorate (and cash in) on Rudolph Valentino's death in 1926 and recorded by both Rudy Vallee and Vernon Dalhart. As the 20th Century went on, the founders' names were reduced to half-remembered legend, then scarcely-remembered trivia, and then were forgotten altogether.

There are some exceptions, of course. Like Lillian Gish, the first great film actress, who sometimes would dance on the set with D.W. Griffith before a day's shoot and who would call him "Mr. Griffith" until the day she died. Unlike many of her peers, Gish lived out the whole of her long life in the movies--her first film was in 1912 (Griffith's An Unseen Enemy), her last was 1987's The Whales of August. An anecdote from the latter is that the director, Linsday Anderson, complimented Gish after a shot: "Miss Gish, you just gave us a marvelous close-up!" To which her co-star Bette Davis replied: "She should--she invented them."

There are only a handful of songs about her, the best being Vic Chesnutt's, an outtake from his 1994 album Drunk; there should be more.

Negri fumes

Oh for the days when vamps were vamps

Not just a bevy of bulbous scamps

The vintage vamp was serpentine

Was madder music and stronger wine.

She ate all her bedazzled victims whole,

Body and bank account and soul;

Yet, to lure a bishop from his crosier

She needed no pectoral exposure,

But trapped the prelate passing by

With her melting mouth and harem eye.

A gob of lipstick and mascara

Was weapon enough for Theda Bara;

Pola Negri and Lya de Putti

And sister vampires, when on duty,

Carnivorous night-blooming lilies,

They flaunted neither falsies nor realies.

Oh, whither have the vampires drifted?

All are endowed, but few are gifted...

Odgen Nash, "Viva Vamp, Vale Vamp."

Bara deigns to be Cleopatra

There are also the great silent movie vamps of Nash's poem, who linger deep in the recesses of cultural memory, and who bequeathed generation after generation of femme fatales. Most of them were Europeans, born to wreak havoc in the New World, like the Polish-born Pola Negri (watch this clip!), who seduced Chaplin and Valentino (Valentino's last words were allegedly "tell Pola I think of her," and she wailed and fainted at his funeral) and who even Hitler fell in love with; her moment of genius is Ernst Lubitsch's The Wildcat. There was the immortal French destroyer Musidora, best known as Irma Vep in Les Vampires, and the ill-starred Lya de Putti, who was born to an Austro-Hungarian Baron and Countess and who died ignobly in America, in a botched surgical operation to remove a chicken bone from her throat.

America had its own vamp exports, like Theda Bara (born Theodosia Goodman in Ohio, and whose stage name was an anagram of "Arab Death") the triumphant vampire of A Fool There Was (and who didn't even make it out of the silent era alive, having become a self-parody by the time she appeared as "Madame Mysterieux" in Stan Laurel's Madame Mystery). And, of course, flapperdom incarnate Clara Bow, commemorated here by the Cleaners From Venus, a British duo who were so lo-fi they only issued homemade cassettes in the '80s. (Originally on the 1986 tape Living With Victoria Grey; collected on Very Best).

He could hardly see another person without wanting to conquer them, to envelop them in the need to attend to him. Yet on occasion, he could be the real fellow, happy to go on a tour, thrilled by the crowd, so ready to be "Charlie" to greet the cry, "Look, there he is!" When great crowds of adoring fans came up to him he held them back a little just by acting out his surprise, his emotion, his being Charlie...Think of the stars who have been crushed by attention, and remember that Charlie exulted in it and was fueled by it , for he felt he deserved it.

David Thomson, The Whole Equation.

...We will sidestep, and to the final smirk

Dally the doom of that inevitable thumb

That slowly chafes its puckered index toward us,

Facing the dull squint with what innocence

And what surprise!

And yet these fine collapses are not lies

More than the pirouettes of any pliant cane;

Our obsequies are, in a way, no enterprise.

We can evade you, and all else but the heart:

What blame to us if the heart live on...

Hart Crane, "Chaplinesque." (Written after Crane saw The Kid.)

I was apprentice to a company of traveling acrobats, jugglers and show-people. That was in England, too, and oh, what hard work it was. I have never had a home worth the name. No association that might have helped me when I was young. Looking back upon it is no joke, and that is why it seems so out of place when I am made much of now.

Charlie Chaplin, interview with Photoplay, 1915.

Lou Reed's murky tribute to Charlie Chaplin, "City Lights," appears on one of his stranger records, 1979's The Bells. I like the track, though it sounds as though Lou, the producer and some hyperactive electronic musician all worked on the thing at different times without ever consulting each other.

Buster Keaton and stand-in

You may argue that Buster Keaton was the finer artist [compared to Chaplin]. But Keaton's perilous survival of physical disaster in his films was matched by the fiasco of his private life. Keaton was a wreck, ruled by others, painfully unable to keep up. Indeed, he was so beaten down in life, one wonders how he mustered the concentration to ensure the serene development of his comic scenes.

Thomson, The Whole Equation.

After the sacred grove of Hollywood

has babbled, flushed, and scattered,

his image quietly endures, surviving

even when the small boat of his career

launches bottomward sudden as an anchor,

his body stubborn as a buoy or pile

fixed on the horizon, until he sinks

(soon to return, grave-faced) beneath

his flat hat floating on the water.

Michael McFee, "Buster Keaton."

"He wasn't very good, was he?" Shirley Temple, in the early '60s, vetoing a proposed tribute to Keaton at the San Francisco Film Festival.

Prove the dire little brat wrong: watch One Week. Or The Boat. Or The Haunted House. Or Cops. Or The Playhouse. Or Neighbors. Or any of the features. And enjoy Curtis Eller's tribute to the man, which can be found on Eller's 2004 record Taking Up Serpents Again.

Marie Prevost and dog, in happier days

The end of the silent era came, as Hemingway once wrote, in two ways: suddenly and all at once. Driven by the upstart studios Warner Brothers and Fox, which were the first studios to embrace synchronized sound, sound films emerged in 1926, gained attention in '27 (with Jolson's The Jazz Singer) and reached critical mass in 1928. By decade's end, there were basically no more silent films being made.

There were many casualties among the actors, like Norma Talmadge, who left Hollywood forever after two flop sound films, and John Gilbert, whose woeful transition was parodied decades later in Singin' In the Rain. Yet perhaps it wasn't just that some actors had squeaky voices or Bronx accents. The talkies appeared at a generational turn--the audience was suddenly ready for most of the old stars to go out; it was as though, subconsciously, the world wanted to purge all of its daydreams and start its fantasies anew. With a Depression, fascism and war on the near horizon, dreams had to be made of sterner stuff.

Nick Lowe's "Marie Provost" (sic) details the lurid end of one of the silent movie queens--found dead of starvation and heart failure in 1937 in her cheap apartment on Hollywood West, her corpse gnawed on by her dog (who, to clear its long-abused name, was not trying to eat his owner but only to wake her). On the essential Jesus of Cool.

You can say, as Norma Desmond did, that the silent films didn't need dialogue, only faces, so that the silent movie stars were the purest gods of all; you could argue, as Chaplin did, that Hollywood had only really learned how to make films just when the silent movie era suddenly ended, setting back innovation a half-decade at least. But as is the case in most religions, a sacrifice had to be made. For the nation of dreamers to come had only just woken up.

"If I Had A Talking Picture of You," written by Lew Brown, Ray Henderson and Buddy DeSylva for the 1929 Fox talkie Sunnyside Up, is a victor's boast. This version, performed by Bing Crosby and Paul Whiteman's Orchestra, is on Paul Whiteman Vol. 1.

Oh No! Will Helen escape from the clutches of the young Marxist?

TO BE CONTINUED!!

Don't miss in Part II: Garbo talks! Harpo honks! Joan Crawford rises from the grave! Mary C. Brown jumps off the Hollywood sign! Ingrid Bergman is denounced on the floor of the U.S. Senate! James Dean has an appointment in Samarra! All in "When You're Terrific If You're Even Good," coming soon to your local movie palace.

No comments:

Post a Comment