Harmonica Frank Floyd, Rockin' Chair Daddy.

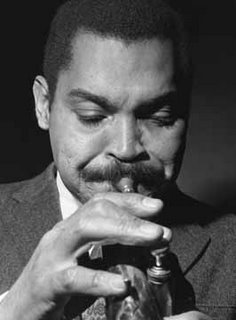

Kenneth Banks, High.

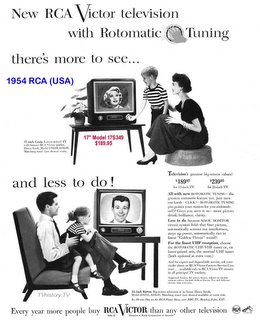

Sam Phillips had finally found what he wanted. It had happened just in time: the blues musicians who Phillips had been recording since 1950 were getting difficult to sign--with growing demand for R&B records from teenagers, inculcated into the music by DJs like Alan Freed, suddenly the obscure and penny-ante business of taping blues artists was becoming competitive and lucrative. By 1954, Phillips had been in legal brawls with larger labels, had watched his most established artists (like Junior Parker, who broke his Sun contract to sign with Duke) fly away and realized that, lacking the budget of an Atlantic or Chess, he was going to be consigned to the minor leagues.

Then, of course, came Sun 209, "That's All Right"/"Blue Moon of Kentucky", in July, and Sun 210, "Good Rockin' Tonight/"I Don't Care If the Sun Don't Shine", in September. Having at last hit a vein of gold, Phillips greatly curtailed his recording sessions so that he could market and promote Elvis Presley.

So Sun blues records became increasingly rare--by 1956, they were all but extinct. One of the last examples of the wild, guttural blues Phillips had routinely captured on disc for four years was Kenneth Banks' "High"--a vulgar, honking glorification of getting rocked to the gills, featuring some psychotic guitar work by Pat Hare (he of "I'm Gonna Murder My Baby" infamy). And "High", like many Sun blues recorded in the mid-'50s, was never released.

As the Sun Records: Blues Years set puts it, Banks is "another blank ledger in the filing cabinet of blues biography." Little is known about the man, other than he was a regular bassist on Sun sessions. "High", recorded on January 8, 1954, featured Mose Vinson on piano and Houston Stokes on drums. Find here.

And when Phillips began recording again in earnest, he focused more on country music--particularly wild, jet-age hillbilly bop. Soon enough would come Perkins, Cash, Orbison and the Killer.

However, Phillips' first attempt to find this sort of country-fried rock & roll had been in 1951, when he recorded an intinerant singer/harmonica player named Frank Floyd. Floyd, born in Toccopola, Mississippi in 1908, had bummed around the country for 40 years, working odd jobs, playing in medicine shows, woodman halls, and on street corners. (Much of the information on Floyd comes from Greil Marcus' Mystery Train.)

Who knows how Floyd and Phillips found each other, but in '51, Phillips was hungry for something he could barely define. "Gimme something different," Phillips told Floyd in the little studio on Union Ave. "Gimme something unique." Phillips passed on the tracks that came out of the session to Chess Records, which released some sides that utterly flopped. This was odd, screeching, simply weird music that no one wanted to hear--the Floyd singles could have been slipped in among the host of scratchy 1920s sides that Harry Smith would collect the following year on his American Folk Music anthology, and none would have been the wiser.

In spring 1954, Phillips and Floyd tried again. The result--Sun 205, "The Great Medical Menagerist"/"Rockin' Chair Daddy", was Phillips' first true rock & roll single, a boast sung by a wild 46-year old man who likely would have scared the hell out of most of the teenagers who bought the record.

Well I never went to college

And I never went to school

So when it comes to rockin'

I'm a rockin' fool!

"Rockin' Chair Daddy" is on Sun Years Vol. 1.

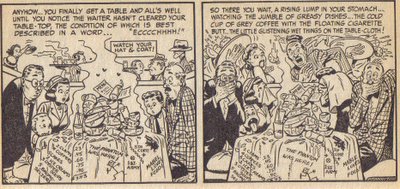

In September '54, one of the greatest bits of American humor ever published (in my opinion, of course) appeared in Mad magazine (issue #16). Called "Restaurant!", it was drawn by the brilliant Will Elder, the Brueghel of comic books, and detailed a hapless family's attempt to get served at a overcrowded chow-mein restaurant, with so much bizarre detail crammed into the margins and backgrounds that ten or twenty reads are needed to get all of it in. I first came across it in The Bedside Mad, one of the best anthologies of the early Mad days, and it's been making me laugh for over 25 years.

Bonus Round

Today's my birthday, so here are some tracks reflecting my state of mind:

The Pretenders, Middle of the Road.

Traveling Wilburys, End of the Line.

"Maybe somewhere down the road aways/You'll think of me and wonder where I am these days. " RIP Roy and George. And to the rest of you, happy weekend.