1955 the ultimate answer to immigration

the ultimate answer to immigration

Sonny Rollins, There's No Business Like Show Business.

Nappy Brown, Don't Be Angry.

Dean Martin, Memories Are Made of This.

Elmer Bernstein, Frankie Machine.

Smiley Lewis, I Hear You Knocking.

Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee, Ride and Roll.

The Turbans, When You Dance.

The Blues Rockers, Calling All Cows.

Marty Robbins, Tennessee Toddy.

The Robins, Smokey Joe's Cafe.

Jon Hendricks and Dave Lambert, Cloudburst.

Sonny Boy Williamson, From the Bottom.A cold spring:

The violet was flawed on the lawn.

For two weeks or more the trees hesitated;

the little leaves waited,

carefully indicating their characteristics.

Finally a grave green dust

settled over your big and aimless hills...Elizabeth Bishop,

A Cold Spring, 1955.

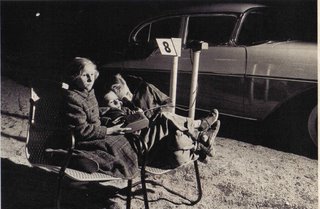

Shall we wind out 1955? Sit down, take a minute. There.

"No Business Like Show Business": After a tiny feint by Ray Bryant on piano and fanfare on drums by Max Roach, Sonny Rollins is off like a shot, bobbing through Irving Berlin's melodic spiral. In Rollins' first solo chorus, he is supported only by George Morrow's bass; in his second, he's pure swagger, bursting with energy and attitude. Bryant provides a fleet dance on the piano, and Roach gives one of the more melodic drum solos ever recorded. The whole track is a thing of joy--taped in Hackensack, NJ, on December 2, 1955. On

Worktime.

In "Don't Be Angry,"

Nappy Brown elongates the first word of the verse, turning the humble "so" into a bit of glossolalia, fattening it into eight or more syllables and twining around it a knotty string of "ell" sounds. (The legend is that Savoy Records head Herman Lubinsky thought Brown was singing in Yiddish.) Brown's competing with Sam "The Man" Taylor's meaty tenor sax solo, and it's hard to pick who wins. Recorded on February 1, 1955 and released as Savoy 1155. On

Don't Be Angry!Dean Martin's "Memories Are Made of This" is Hollywood folk-pop, with Dean supported by the

Easy Riders. For a Capitol Records A-list pop recording from 1955, this is a surprisingly spare production--just guitar providing a trellis for the singers. And Dean's vocal presages two decades of Elvis Presley ballads. Recorded on October 28, 1955 and released a month later as Capitol 3295 (it was a #1 hit by year's end). On

Capitol Collectors Series.Elmer Bernstein's "Frankie Machine" is from the soundtrack to

The Man With the Golden Arm. It's the sort of brassy, frenetic piece that would become standard-issue for most police and 'social problems' dramas for the next 15 years. There's a lot to enjoy, from Shelly Manne's drumming (a hybrid of cool jazz and marching band) to Shorty Rogers' solo on the flugelhorn (!) to the way the brass section sizzles to a boil. Recorded in LA on December 15, 1955; find

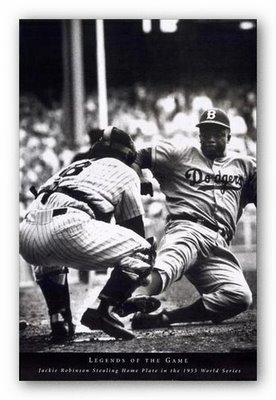

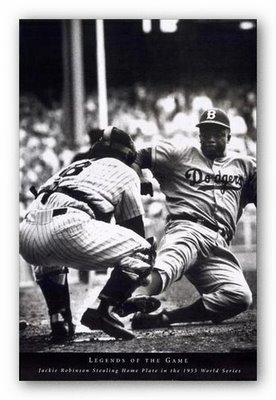

here. The Brooklyn Dodgers finally won it all. And two years later, the team got moved to Los Angeles, a crime still unatoned for.

The Brooklyn Dodgers finally won it all. And two years later, the team got moved to Los Angeles, a crime still unatoned for."I Hear You Knocking": What else can you say? This is rock and roll; this is the majesty of New Orleans. Dave Bartholomew, Huey "Piano" Smith, Smiley Lewis--they're all there in the groove. Recorded in March (or May), 1955, and released in July as Imperial 5356; find

here.

"

Gimme your ticket--lonnnnng as my right arm." "Ride and Roll," a forgotten but driving electric blues, was created by an all-star team: Sonny Terry on harmonica and vocal, Stick McGhee and Brownie McGhee on guitars, and Milt Hinton on bass. Recorded on November 7, 1955, and released as Groove 0135. On

That's All Right.The Turbans were from Philadelphia, and their fleeting taste of fortune is the early rock & roll era (heck, any pop era) in miniature. Four kids--Al Banks (lead), Matthew Platt, Chet Jones and Charles Williams--get an act together (and yes, they wore turbans sometimes); they find a manager; the manager contacts a local R&B label; they cut a hot record that gets airplay, at first locally, then nationally; the group tours with top names; the next single keeps the momentum going, but the third stiffs; the group loses steam, further singles flop, their label drops them; a stay on another label produces little of merit; the group breaks up. But they left a shard of immortality behind--"When You Dance" smokes. Recorded in summer '55 and released as Herald 458. Find

here.

"Calling All Cows," a Chicago blues novelty scratched together in Nashville, was by the Blues Rockers--Earley Dranne (vox, guitar), PT Hayes (harmonica), Lazy Bill Lucas (p). Issued as Excello 2062. You can never have enough tracks with guys mooing as background vocals. Find on the now out of print

Excello Story Vol. 1."Tennessee Toddy," in which Marty Robbins goes catting around with a nymphet and gets a crack on the head, is on

Essential Marty Robbins.The voice of America (or at least, how it used to sound): goofy, clever, a bit ridiculous, hyperactive, irreverent--it's all in Leiber and Stoller's "Smokey Joe's Cafe." It reminds me of when Nabokov emigrated to the U.S. during WWII, having barely escaped Nazi Germany and Vichy France, and the first thing that occurred when he arrived was that a pair of customs officers opened his suitcase, found some boxing gloves and began sparring with each other.

"Smokey Joe's" was one of the finest records by the fantastic

Robins, who broke up soon after its release--from their embers rose the far more successful (commercially, not artistically) Coasters. First released in August 1955 as Spark 122; then almost immediately after as Atco 6059, when Atlantic bought the rights and snagged Leiber and Stoller in the process. On

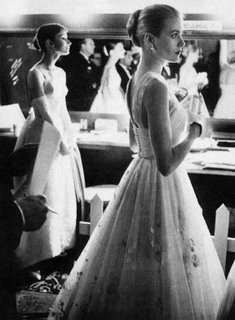

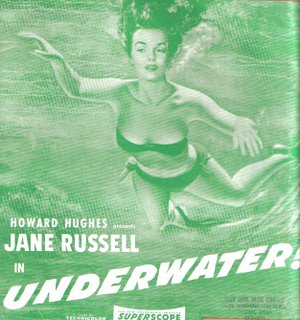

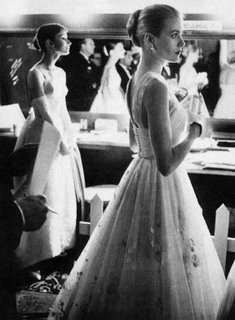

Doo Wop Classics. Helen and Aphrodite, in their 1955 incarnations

Helen and Aphrodite, in their 1955 incarnationsJon Hendricks, before he joined Annie Ross and Dave Lambert in 1958 as a formal trio, had been experimenting with vocalizing jazz performances, fitting lyrics over what been improvised instrumental solos. In 1955, Hendricks teamed up with Lambert for the first time to convert Benny Harris and Leroy Kirkland's "Cloudburst" (using Sam "The Man" Taylor's recording as template) into a run of vocal acrobatics, with the "

shave and a haircut--two bits" motif as a hook. The track features Hendricks, Lambert and four other singers (Marian Workman, Jerry Duane, Butch Birdsall and some other guy, whose name is apparently lost to history).

Recorded on May 1 (or 12), 1955 and released as Decca 29572; it can be found on

Sing a Song of Basie.The core of Sonny Boy Williamson's "From the Bottom" is the fantastic beat, which sounds like someone is thumping a metal water can. B.B. King provides a hot guitar solo and Williamson's minimalist lyrics are a fun puzzle as well. (Sonny's girl is good-looking enough to land her a role in Hollywood, and he's going with her to see what happens. Or maybe it's just about how much Sonny likes his woman's ass.) Actually recorded on November 12, 1954, but let's let it through. Issued as Trumpet 228, the last Trumpet single ever released, and found on

Cool Cool Blues.Films of '55Another holy monster of a year.

The Night of the Hunter. In which you experience the worst childhood nightmare imaginable--you are orphaned, a horrific step-parent appears to take you away, your preacher is an emissary of darkness.

Sommarnattens leende (Smiles of a Summer Night). Bergman's

A Midsummer Night's Dream.The Ladykillers. Genius performances by Alec Guinness, Peter Sellers and Herbert Lom, but the soul of the movie is Katie Johnson, playing Mrs. Wilberforce, the last Victorian lady. And yes, the Tom Hanks remake is a piece of crap.

The Night My Number Came Up. Someone put this out on DVD: I'm begging you. Hell, I'd take a VHS copy.

Rebel Without a Cause. While rock & roll precedes this film by years, you could make the case that "Rebel" somehow stamped rock music in its own image, despite not having a note of it on the soundtrack. The whole thing is a frenzied teenage aria; its actors seem on the brink of going into hysterics.

Kiss Me Deadly. Mike Hammer: "

You were out with some guy who thought "no" was a three-letter word. I should have thrown you off that cliff back there. I might still do it."Pather Panchali.The Phenix City Story.Nuit et Brouillard (Night and Fog). Ten years after the camps were closed, the world had barely begun to admit what had happened there. After this film, there were no more excuses.

This Island Earth.Ordet.Muerte de un Ciclista (Death of a Cyclist).Count Three and Pray.Lola Montès/

French Cancan. Two late spectacles by Ophuls and Renoir, in which the masters return, after a long journey, to the theatres and circuses of their youth.

Happy weekend, happy Easter, happy Passover, etc.