IWW headquarters after Palmer raid, NYC, 15 November 1919.

Edward Elgar, Cello Concerto: 2nd Movement.

Al Bernard with the Kansas Jazz Boys, Bluin' the Blues.

Wilbur Sweatman's Jazz Orchestra, Kansas City Blues.

All Star Trio, Shimmee Town.

Louisiana Five, Clarinet Squawk.

Nora Bayes, Just Like a Gypsy.

Art Hickman's Orchestra, Rose Room.

Art Hickman's Orchestra, On the Streets of Cairo.

Premier Quartet, Dixie Is Dixie Once More.

Jim Europe's 369th Infantry Jazz Band, Memphis Blues.

Jim Europe's Four Harmony Kings, One More Ribber to Cross.

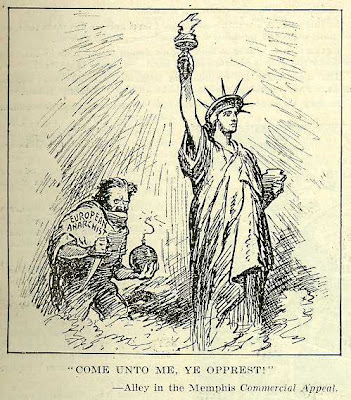

We ask you insistently to give us more frequent, definite information on the following. What measures have you taken to fight the bourgeois executioners; have councils of workers and servants been formed in the different sections of the city; have the workers been armed; have the bourgeoisie been disarmed; has use been made of the stocks of clothing and other items for immediate and extensive aid to the workers, and especially to the farm laborers and small peasants; have the capitalist factories and wealth in Munich and the capitalist farms in its environs been confiscated; have mortgage and rent payments by small peasants been canceled; have the wages of farm laborers and unskilled workers been doubled or trebled; have all paper stocks and all printing-presses been confiscated so as to enable popular leaflets and newspapers to be printed for the masses;...

Has the six-hour working day with two or three-hour instruction in state administration been introduced; have the bourgeoisie in Munich been made to give up surplus housing so that workers may be immediately moved into comfortable flats; have you taken over all the banks; have you taken hostages from the ranks of the bourgeoisie; have you introduced higher rations for the workers than for the bourgeoisie; have all the workers been mobilized for defense and for ideological propaganda in the neighboring villages?

The most urgent and most extensive implementation of these and similar measures, coupled with the initiative of workers’, farm laborers’ and—-acting apart from them—-small peasants’ councils, should strengthen your position. An emergency tax must be levied on the bourgeoisie, and an actual improvement effected in the condition of the workers, farm laborers and small peasants at once and at all costs.

With sincere greetings and wishes of success.

Letter from Vladimir Lenin to the leaders of the Soviet Republic of Bavaria, 27 April 1919 (see interlude below).

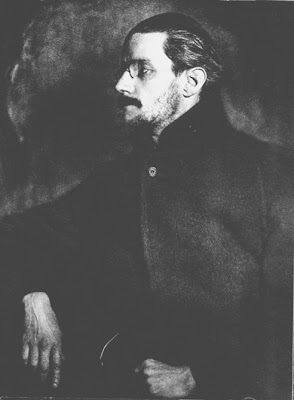

Sir Edward Elgar, eminent Edwardian composer of the "Enigma Variations" and "Pomp and Circumstance Marches," was broken by the war. He had composed little since 1914, writing to a friend that "I cannot do any real work with the awful shadow over us." Finally in 1918, after having his tonsils removed (at age 61) and enduring severe pain for days on end, he sketched what would become the opening theme of a concerto for cello and orchestra. In the spring and summer of the following year, working in his Sussex cottage, using an old upright Steinway piano, Elgar finished the concerto. "A real large work, and I think good and alive," he wrote upon its completion. It was his last masterwork, a staggeringly beautiful piece of music.

Many critics have heard in the concerto a requiem, not just for the millions killed during the war but for the end of a way of life--the death of the pastoral, of the golden age of classical music, the Empire, the 19th Century, what you will. The first movement begins with a lament on the cello, followed by the opening theme. The second movement, included here, is considered lighter in tone, but there is darkness visible as well--in the cello's fleeting, darting melodic line, bowed and then plucked; in the nearly modernist severity of the arrangement. When the release comes, midway through the movement, it has the sense of someone desperately reviving a faded memory, convincing themselves they were once young or free.

Elgar's Cello Concerto in E Minor, op. 85, premiered in London on 27 October 1919. The 1965 recording sampled here is the essential interpretation: the 20-year-old Jacqueline du Pré, playing the Davidov Stradivarius, with Sir John Barbirolli and the London Symphony Orchestra. (Du Pré and Barbirolli's recording basically canonized the Elgar Concerto, which had been ignored and dismissed in the '30s and '40s, its reputation having never recovered from poor reviews of the debut concert). (And here are the third and fourth movements of the du Pré/Daniel Barenboim concert shown earlier.)

James Joyce in Zurich, 1919.

Al Bernard, along with Emmett Miller (who we'll be meeting fairly soon), was the last of the great blackface minstrel singers.

Bernard, born in New Orleans in 1888, came to New York City in a traveling minstrel show after the end of WWI and wound up staying there, spending the '20s in vaudeville, on the radio and making records (sometimes duets with Ernest Hare, in which Bernard sang like a woman). He was known as "The Boy From Dixie," and while his often-racist music discredited him with later generations, Bernard proved to be a link between minstrelsy, blues and Western swing.

El Lissitzky, Beat the Whites With the Red Wedge.

Bernard had a talent for singing jazz and blues and cut a number of records in those emerging styles, including three 1921 sides with the fading Original Dixieland Jazz Band. The excellent (if lyrically offensive, natch) "Bluin' the Blues," which Bernard recorded with an unknown studio group dubbed the "Kansas Jazz Boys," was written by the ODJB's pianist, Henry Ragas, who was a casualty of the Spanish Flu epidemic in early 1919.

Recorded ca. June 1919 and released as Gennett 4544, c/w "Everyone Wants a Key to My Cellar"; on Ragtime to Jazz.

Wilbur Sweatman's take on "Kansas City Blues" finds Sweatman once again crafting an advanced form of jazz that wouldn't reach the masses until at least the mid-'20s. Sweatman's clarinet work here seems designed to set the bar for his successors Sidney Bechet and Johnny Dodds.

Recorded 24 March 1919 and released as Columbia A2768; on Jazzin' Straight Thru Paradise.

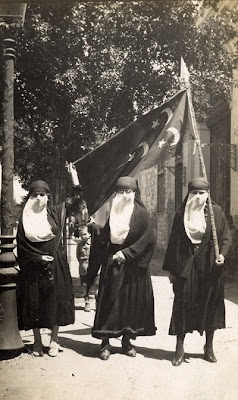

Women protesting during the Egyptian Revolution, Cairo, 1919.

The All-Star Trio (saxophonist Wheeler Wadsworth, pianist Victor Arden and xylophonist George Hamilton Green) were a popular dance band in the late teens and early '20s; their odd instrumental line-up (a sort of first-draft version of the Modern Jazz Quartet) shows how the standard "jazz band" composition had yet to solidify.

The Trio's "Shimmee Town," a tune from the Ziegfeld Follies of 1919, was recorded in New York on 31 July 1919 and released as Edison 50590-L/Edison 3871; find here.

Before the band broke up: Kamenev, Lenin and Trotsky at the 8th Party Congress

The Louisiana Five (clarinetist Alcide "Yellow" Nuñez, pianist Joe Cawley, trombonist Charlie Panelli, banjoist Karl Berger and drummer Anton Lada) was a New Orleans-based group, the top rival to the Original Dixieland Jazz Band. Nuñez had played with the ODJB in 1916, although relations had soured by the time he formed the Five (in part because Nuñez tried to copyright "Livery Stable Blues" without informing the rest of the ODJB).

"Clarinet Squawk," one of the Five's better recordings, is aptly named, as Nuñez's high and shrill clarinet (serving as the lead melodic instrument, as there is no cornet) dominates the track. A son of the New Orleans parade bands, Nuñez is more an embellisher than an improviser, his spotlit performance here as much the product of technology (acoustic recording favored trebly instruments like the clarinet) as it is of design.

As "Squawk"'s original disc jacket copy reads: "It sure does squawk but musically so, if you like cyclonic jazz, played by a quintet which has steeped its musical interpretive qualities in a concentrated essence of contortive jungle music." (from Tim Gracyk.)

Recorded 12 September 1919 and released as Edison 50609-R; in this archive.

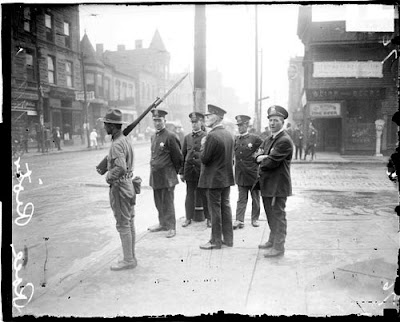

Soldier, policemen during the Chicago race riot, Douglas (South Side), July 1919.

I thought I was done with Nora Bayes in this survey, but as there seems to still be a demand for Ms. Bayes (according to the comments box), here's a fine 1919 disc, one of her biggest hits.

Recorded 11 September 1919 and released as Columbia A-6138, c/w "In Your Arms"; in this archive.

Interlude: scenes from the mayfly countries

The Bavarian Soviet Republic (April-May 1919)

The Hungarian Soviet Republic (March-August 1919)

The Slovak Soviet Republic (16 June-7 July 1919)

Beckmann, The Night.

One of the drummer and pianist Art Hickman's first gigs was heading a dance band that entertained the Pacific Coast League's San Francisco Seals, a minor league baseball team that one day would have the young Joe DiMaggio on its roster, while the Seals were training in Sonoma, Calif. (A March 1913 San Francisco Bulletin article about the Seals and Hickman's band is the earliest-found print appearance of the word "jazz".)

Hickman, in an interview with the San Francisco Chronicle in 1928, was blunt about where he had learned his trade: from black honky-tonks along the Barbary Coast that he had frequented as a delivery boy for Western Union. "There was music. Negroes playing it. Eye shades, sleeves up, cigars in mouth. Gin and liquor and smoke and filth. But music! There is where all jazz originated."

Hickman, however, wasn't playing hot, dirty jazz in the late '10s, but rather streamlined, smoothed-down "society" jazz, cooked for mass consumption. He and his band headlined at the Rose Room, in San Francisco's St. Francis Hotel (which would provide the title to his most famous composition). In 1919, Columbia Records gave him a contract and sent a private Pullman car to take Hickman and his band cross-country. It was a far cry from the dive bars of the Barbary Coast.

Ernst, Aquis Submersus.

So the Art Hickman Orchestra were refiners and society jazzmen, but they could swing and improvise and often had unusual and intricate arrangements. For example, the Hickman Orchestra often had the lead melody carried by a pair of saxophonists, Clyde Doerr and Bert Ralton, at a time when the saxophone was mainly considered something of a circus novelty.

The band cut a string of records for Columbia in the fall of 1919, generally "exotic" pieces like "The Streets of Cairo" (which heats up a bit in the opening section when the drummer tries to start something) or prime dance-hall pop like "Rose Room," which features Doerr and Ralton smoothly improvising over a steady beat, as well as an impressive piano solo by Frank Ellis.

One can credibly claim that Hickman is the godfather of mainstream jazz--without him, there is no Benny Goodman, Artie Shaw or Glenn Miller. Hickman wouldn't consider it a compliment, as he seemed to consider jazz to be beneath him. "Jazz is merely noise, a product of the honky-tonks, and has no place in a refined atmosphere. I have tried to develop an orchestra that charges every pulse with energy without stooping to the skillet beating, sleigh bell ringing contraptions and physical gyrations of a padded cell," he told Talking Machine World in 1920.

In an Examiner interview from the same period, he said: "People [in New York] thought who had not heard my band. . .that I was a jazz band leader. They expected me to stand before them with a shrieking clarionet and perhaps a plug hat askew on my head shaking like a negro with the ague. New York has been surfeited with jazz. Jazz died on the Pacific Coast six months ago..." Ah yes, jazz was dead by 1920. (Much of this information is from Bruce Vermazen's piece, linked to at the start of the Hickman section.)

Hickman grew tired of touring and of New York, and in the early '20s returned to the West Coast, where he played (along with a Florida stint) until his death a decade later. He left his throne up for the taking, and an ambitious Denver bandleader named Paul Whiteman, who had run a dance band in a rival San Francisco hotel during Hickman's Rose Room tenure, prepared to move.

"Rose Room," recorded 19 September 1919, was released as Columbia A2858; "On the Streets of Cairo" was recorded the day before and released as Columbia A2811. Both are on The San Francisco Sound.

Lillian Gish, Richard Barthelmess in Griffith's Broken Blossoms

Two homecomings. Somewhere in the South, a returning regiment parades through the center of town, the paradegoers wearing their Sunday finery, the soldiers showing off the dances they picked up (among other things) in France. Everyone's elated, and most of all, order is restored, especially in the racial hierarchy. Dixie is Dixie once more, the singers affirm, a fervent wish backed by a quiet threat.

(Recorded by the studio group the Premier Quartet, also known as the American Quartet, including Billy Murray, ca. June 1919 in New York and released as OKeh 1226-B; find here.)

Pechstein, cover of An Alle Künstler.

Another homecoming up north: The 369th Infantry Regiment, an all-black regiment (known as the "Harlem Hellfighters") is just back from France. Led by James Reese Europe, the 369th's jazz band makes a tour of Eastern cities, causing a sensation whenever it rolls into town.

Europe, along with being a bandleader, had become an impresario, something of the black equivalent of Florenz Ziegfeld. Europe's shows were now stage revues, complete with spirituals, jazz, comedy bits, classical performances and sentimental weepies, performed by an array of acts. (One, the Four Harmony Kings, served as Europe's vocal quartet, and recorded for Pathé as "Lt. Jim Europe's Four Harmony Kings".)

Sen. Morris Sheppard meets a tall cowboy (Shorpy).

On May 9, 1919, Europe had two shows at Boston's Mechanic's Hall, with an encore performance for Gov. Calvin Coolidge on the State House steps set for the following day. Europe was fighting a bad cold but managed to get the matinee show over well enough. (Al Jolson was in the audience.) There was trouble, however, with his drummer, Herbert Wright. Wright, an ill-tempered, mentally-unstable dwarf, had a habit of disrupting shows by laughing and walking about on stage. During the evening performance, Europe noticed Wright acting up and, during an intermission, called Wright into his dressing room to admonish him.

Wright, feeling disrespected (especially after he was hustled out of the dressing room when the tenor Roland Hayes stopped in to pay his respects to Europe), snapped. He pulled out a pocket knife and charged back into the dressing room, saying he was going to kill Europe. Europe picked up a chair to keep Wright at bay, but then, for a reason his friends never understood, relaxed and put the chair down. Wright threw himself over the chair and stabbed Europe in the neck. Europe died in the hospital a few hours later; Wright later got ten years in prison.

So it was that the life of the most renowned and ambitious African-American bandleader of his generation ended in an absurd backstage murder. They buried Europe in Arlington Cemetery, with the rest of the heroes.

Europe's take on "Memphis Blues" (he finally recorded W.C. Handy's blues anthem, two months before Europe died) was cut on 7 March 1919 and released as both Pathé Frere 22085 and Perfect 14111-B. And the Four Harmony Kings' "One More Ribber to Cross," recorded the day before Europe was killed, served as his epitaph. It was released as Pathé 22187. Find on 369th Infantry Band and Earliest Negro Vocal Groups Vol. 2.

Farewells: A number of fine blogs have called it a day recently, including Five Bucks on By-Tor and Setting the Woods On Fire. Most of all, a very sad goodbye to my friend Amy's Shake Your Fist. And read just three things!

Next: Paradise Is Just a Curse