Dwight D. Eisenhower, Address to the Republican National Convention (excerpt).

Buddy Holly, Changing All Those Changes.

Charlie Feathers, Tongue-Tied Jill.

Janis Martin, Will You Willyum.

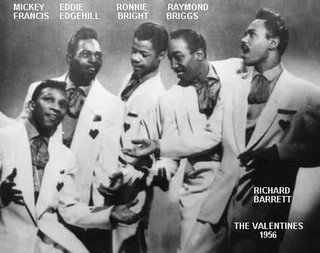

The Valentines, Woo Woo Train.

Tony Bennett, The Boulevard of Broken Dreams.

Art Tatum and Ben Webster, All The Things You Are.

Miles Davis (with John Coltrane), Dear Old Stockholm.

Richard Wilbur, Love Calls Us to the Things of This World.

Chuck Berry, Brown-Eyed Handsome Man.

The Rockers, Down in the Bottom.

Lefty Frizzell, Just Can't Live That Fast (Any More).

Sanford Clark, The Fool.

Sonny Knight, Confidential.

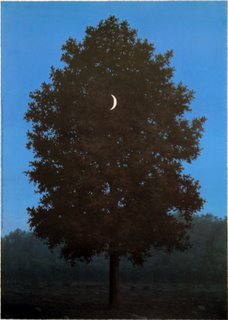

Jeri Southern, No Moon At All.

Chuck Willis, It's Too Late.

The Spaniels, You Gave Me Peace of Mind.

Peggy Lee, It Never Entered My Mind.

Ready? Get a cup of coffee and enjoy.

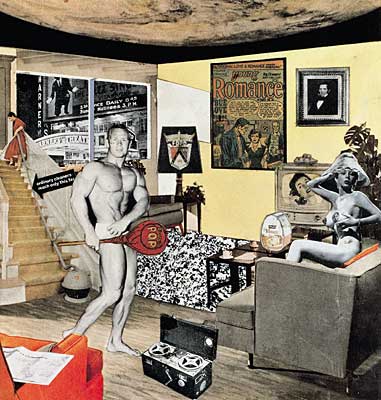

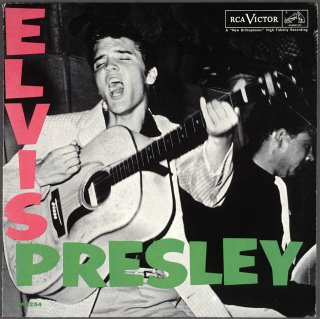

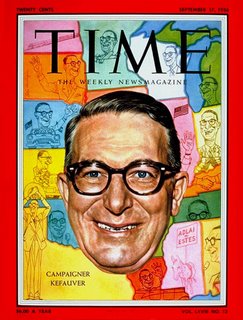

Dwight Eisenhower was re-elected in November '56 in one of the more anti-climactic American electoral victories of the century (even Robert Kennedy, disgusted with Adlai Stevenson, voted for Ike). The more one reads about Eisenhower, the odder he seems, talking about the horror and absurdity of nuclear war in the middle of his acceptance speech, offering as his final statement to the nation a grim warning about the "military industrial complex".

This small excerpt is from Eisenhower's acceptance speech on August 23, 1956, from the Cow Palace in San Francisco. Entire speech (warning--long and dull) is here.

Nixon never looked prettier

Buddy Holly's first Nashville sessions for Decca produced nothing close to a hit record, so Holly returned home to Texas, a bit chastened. Owen Bradley, his producer in Nashville, expressed regret years later:

"Buddy didn't fit into our formula any more than we did into his ... it was like two people speaking different languages ... our musicians were fantastic at what they were doing but they just didn't know how to do what he was doing..."

During the early spring of 1956, Holly went out to Nor Va Jak Studios, in Clovis, New Mexico, to record a few demos with Norman Petty. Suddenly, things began to align--the tracks were harder and had a vitality Holly's first Nashville session had lacked. Exhibit A: "Changing All Those Changes," which Holly performs as if he came out of the cradle singing rockabilly. (He would record a more professional version in Nashville that summer.) Less than a year later, Holly made "That'll Be the Day" at Nor Va Jak, and nothing would be the same again. On Reminiscing/Showcase.

Charlie Feathers was another aspiring rock & roll contender, who recorded for seemingly every independent label around, including Sun. One of his early singles was "Tongue Tied Jill," a fairly tasteless track in which Charlie woos a stuttering girl, interrupted by twelve bars of fierce rhythm guitar. Recorded appropriately on April Fool's Day, 1956, and issued in June as Meteor 5032. (Meteor was Sun's biggest rival in Memphis--Feathers went there after getting frustrated with Sam Phillips' apparent indifference.) On Get With It.

"Will You Willyum": divine rockabilly from the awesome Janis Martin, a 15-year-old who RCA marketed for a time as the "female Elvis." Recorded on March 8, 1956 and released as RCA 6491. Find here.

The Valentines' "Woo Woo Train" is a gift from regular reader Vlad B., who has this to say about it:

"In and of itself, the song does not necessarily stand out among the others of its kind, but it contains arguably the wildest and most primal sax break I've ever heard on a doo-wop record. The man behind it is Jimmy Wright (who is also responsible for pretty much all the sax work on the Gee/Rama label, i.e. all the Frankie Lymon and the Teenagers recordings). Wright has been the inspiration for a lot of trademark mid-50s sound before electric guitars took over."

He's not exaggerating about the sax break. More info on Jimmy Wright. Released as Rama 196 in April '56, find here.

"Boulevard of Broken Dreams": One of Tony Bennett's most baroque performances, complete with a troupe of castanet players. "Boulevard" was one of the oldest songs in Bennett's repertoire--he recorded it on a demo disc in 1949, which inspired Mitch Miller to sign Bennett to Columbia, and also did a full studio version in 1950. This take was recorded September 13, 1956 and released on the album Tony the following year. Find on Essential Tony Bennett.

Twilight of the masters--Art Tatum and Ben Webster take on Jerome Kern's "All the Things You Are":

Benny Green: In the first chorus, Art performs all kinds of harmonic sorcery so that after 36 bars the game is over, the performance is done, and everyone but Tatum can pack up and go home. Enter Ben, who plays more or less the written melody, embellishing here and there...by the end of the second chorus, Ben has established his parity, with the result that (Tatum's) beautifully subdued stride figures bubbling out of the piano sound more effective than ever.

The track was recorded in Los Angeles on September 11, 1956, with Red Callender (b) and Bill Douglass (d). Less than two months later, Tatum was dead of uraemia complications. Find on Tatum Group Masterpieces Vol. 8.

When '56 began, John Coltrane was still considered a relatively unknown player with questionable potential, having had an undistinguished career to date, mainly working as a sideman for the likes of Earl Bostic and Eddie "Cleanhead" Vinson; some players considered his tone to be abrasive and his soloing skills to be weak. Miles Davis had attended a session in which Sonny Rollins had utterly outclassed Coltrane, and so when Coltrane's name came up as a candidate for his new group, Davis "wasn't excited," as he wrote years later in his autobiography.

Yet Coltrane was at last coming into his own--he dueled Sonny Rollins to a draw in the latter's "Tenor Madness," and he landed the saxophone slot in Davis' first quintet, which during the year churned out a mess of recordings in order to get Davis out of his Prestige contract and into Columbia, Davis' home for the rest of his life.

Miles' First Quintet is the jazz equivalent of the 1927 Yankees--a group of ridiculously staggering talent, with Davis on trumpet, Coltrane on sax, pianist Red Garland, bassist Paul Chambers and Philly Joe Jones on drums. It was an erratic, volatile group--most of the players had drug problems, causing Davis to have to routinely sack them (Garland would be replaced by Bill Evans, Jones by Jimmy Cobb and Cannonball Adderley often subbed for Coltrane).

"Dear Old Stockholm" is from Round About Midnight, Davis' first Columbia LP. "Stockholm," which closed out the record, is a harbinger of Davis' modal recordings of the late '50s. Using his Harmon mute to create a harsher, smoky tone, Davis leads the group through the opening passages; Chambers gets a lengthy two-chorus solo, with Garland breaking in to offer the main theme as a bit of sustenance; and then (around 3:25) Coltrane struts in like a bantam. Davis sits back, then provides a masterful, crafty response. Recorded on June 5, 1956.

Hungary, 1956: a dream deferred

American poetry, two variants:

Richard Wilbur's Love Calls Us to the Things of This World was published in Things of This World. Find in Collected Poems.

"Outside the open window,

the morning air is all awash with angels..."

And Chuck Berry's "Brown-Eyed Handsome Man," whose lyric combines Burma Shave rhymes and Jackie Robinson imagery. Recorded on April 16, 1956, and released as Chess 1635; find on Gold.

The Rockers' "Down in the Bottom" is a throwback to a waning sound, that of the early, heavy R&B, but I for one like throwbacks. Spearheaded by Ike Turner, the track was released as Federal 12273 c/w "Why Don't You Believe." I don't think it's available on CD.

Lefty Frizzell's "Just Can't Live That Fast (Any More)" has some of my favorite lines: "I remember back when/the fun'd begin/noon the next day 'fore I'd come in." The greatest hangover anthem ever. Recorded on May 22, and issued the next month as Columbia 21530. Find on Look What Thoughts Will Do.

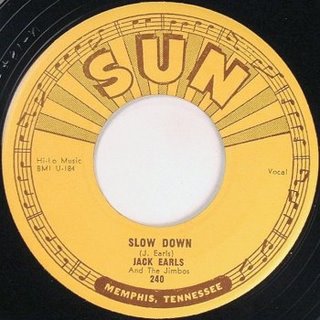

Sanford Clark was discovered by a young disc jockey named Lee Hazelwood, who was looking for someone to record a song he had just written. They recorded the track with Clark's buddy Al Casey on guitar; it was released on the tiny label MCI (no relation to the phone company) and stiffed. Clark was delivering Canada Dry bottles in Phoenix when Dot Records signed him and re-issued Hazelwood's "The Fool," which became a top 10 hit by the summer.

Clark spent the next decade trying to get lightning to strike again. It didn't. Clark ultimately grew tired of the hunt and went on to work in construction and to become a top blackjack player. "The Fool" was released in May 1956 as MCI 1003 and a month or so later as Dot 15481. Elvis finally covered it in 1970, in a masterful take that would be one of Presley's last great recordings. Find the original here.

"Confidential" offered a similar story. Recorded by Sonny Knight (born Joseph Smith), it was first issued on the small Pasadena-based Vita label until, once again, Dot purchased it, reissued it, and got a top 20 smash out of it. And Knight never got another hit. Released as Vita 137 and Dot 15507, and can be found here.

"Confidential" was written by Dorinda Morgan, who was a sort of surrogate mother for Knight (Knight lived at their house and recorded in the little studio Dorinda and her husband had set up). Years later, she would help discover the Beach Boys.

And you can't have enough Jeri Southern--the swinging "No Moon At All" was recorded on November 20, 1956, and issued on the 1957 LP Jeri Gently Jumps. Find on The Very Thought of You.

Finally, three states of mind:

Joy: The Spaniels' "You Gave Me Peace of Mind." Issued on Vee-Jay 229 in December '56. On 40th Anniversary.

Despair: Chuck Willis' "It's Too Late." Recorded April 13, 1956 and issued as Atlantic 1098. Find on Stroll On. Later covered by Derek and the Dominos.

And sad acceptance: dim the lights for Peggy Lee. Her version of Rodgers and Hart's "It Never Entered My Mind" was recorded on June 5, 1956 and issued a year later on the LP Dream Street; it can be found here. It's one of my favorite performances of hers--Lee's vocal is just heartbreaking.

Ave et vale

Gibbon, upon finishing his account of the period first recorded by the Roman historian Ammianus Marcellinus, wrote of his debt to his predecessor:

"It is not without the most sincere regret that I must now take leave of an accurate and faithful guide, who has composed the history of his own times without indulging the prejudices and passions which usually affect the mind of a contemporary."

I will say the same about Allen Lowe, whose American Pop overview of music, which begins with the Unique Quartette in 1893, ends with the year 1956. Lowe's list of essential recordings has been of invaluable help in picking tracks for this blog--I never would have heard some of the choicest obscurities ("Can't Love Me and My Money Too," "E String Rag," "Shadow My Baby", "Pegasus", etc.) without Lowe's guidance.

Lowe's book and 9-CD set are both long out of print, but if you do ever have the opportunity, try to pick them up.

Films of '56

Seven Men From Now. Seventy-eight minutes long, not a moment wasted. The first and finest of Budd Boetticher and Randolph Scott's great string of Westerns.

Un condamné à mort s'est échappé (A Condemned Man Escapes).

Bigger Than Life. With this, an obsessive drug movie starring James Mason, the high period of Nicholas Ray comes to a close. Afterward was frustration and obscurity. Still, with They Live By Night, In a Lonely Place, The Lusty Men, Johnny Guitar, Rebel and others, Ray secured his claim as the essential American director of the period.

The Searchers. Overrated where "Seven Men" is neglected, its themes strip-mined by countless imitators, it's still pretty phenomenal.

The Killing. Kubrick at his leanest, with an ending that has rarely been equalled in its blunt fatality. "What's the difference?"

Invasion of the Body Snatchers.

While the City Sleeps.

Le Mystère Picasso.

Aparajito. Might be a 1957 film.

Forbidden Planet.

The Last Hunt. Actual buffalo were shot during the filming.

Anastasia. Ingrid Bergman: the Restoration.

Bandido. Seriously, everything Bob Mitchum did in the '50s is worth seeing.

Soshun.

The Man Who Knew Too Much. Que sera sera.