Gerry Mulligan/Chet Baker Quartet, Lullaby of the Leaves.

Gerry Mulligan/Chet Baker Quartet, Soft Shoe.

Dave Brubeck and Paul Desmond, You Go to My Head.

“Cool” jazz, or "West Coast Jazz", like most subheadings in music histories, is an overly vague and at times inaccurate term--the only things cool jazz musicians had in common is that they recorded on the West Coast in the fifties, usually for the handful of local independent labels (Fantasy, Pacific) that emerged around the same time; they were mostly white; and their music often forsook blues standards and influences and the frenetic pace of bebop, pushing instead for clarity, quiet intensity and melody.

The core cool jazz records were recorded in just a few years, the early to mid-'50s, and the style soon congealed into a cliché. Think of the hep cool jazz band in 1957’s The Sweet Smell of Success, who already seem to be a parody – wearing sunglasses indoors at night, watching only themselves not the audience, immaculately dressed in matching suits, playing moody, spare music tailor-made for someone's quiet breakdown. Cool jazz devolved into music for the LP age, for the archetypal '50s swinging bachelor, with his wet bar, hi-fi set and Playboy subscription.

Still, long before its current incarnation as incidental music for Starbucks barristas, cool jazz was at its peak the hippest thing in the United States. This was music for, if not the future, then at least the present; urban, disaffected sounds--no more renditions of corny stuff like “When It's Sleepy Time Down South," or “Rocking Chair” or warhorses like "After You’ve Gone". It was not frantic music, it was not four-to-the bar, brass-heavy stomp crafted to be heard over the din of a loud dance hall (the dance halls had all closed anyhow)–it was music to be played, as James Baldwin wrote in Another Country, after all the squares had gone home.

Ted Gioia: cool jazz had “an acute sensitivity to instrumental textures; a studied avoidance of the easy licks and empty clichés of bop and swing; in their place, fresh, uncluttered lines, cleanly played. And above all, the band overcame the jazz musician's greatest fear: the fear of silence.”

When the 1950s began, Gerry Mulligan, the baritone saxophonist who had first made his mark with the Miles Davis Nonet in the late '40s, was hitchhiking his way from New York to California. Mulligan found work in Stan Kenton's big band and, when offered a Monday night gig at the Haig, a small restaurant across from the Coconut Grove in Los Angeles, Mulligan formed a quartet of trumpeter Chet Baker, Bob Whitlock and Carson Smith alternating on bass and Chico Hamilton on drums.

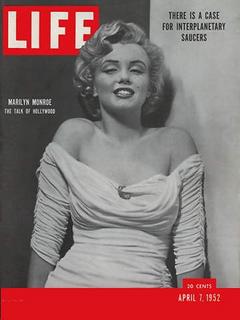

Baker has taken some knocks over the years by critics, who have complained his tone and his range were limited, that his singing was even worse, but listeners always flocked to him, whether it was because of his matinee idol looks (he was one of the first jazz musicians who could’ve played himself in a movie of his life) or his ability to almost flawlessly develop a melody and convey a deep sense of mood--at the latter task, no one but Miles Davis could best him.

The Mulligan/Baker quartet began recording in the summer of 1952 at the Laurel Canyon bungalow owned by engineer Phil Turetsky. A session in the bungalow on August 16 yielded “Lullaby of the Leaves” and “Bernie’s Tune”, the quartet's first masterpieces--Richard Bock launched the Pacific Jazz label with a two sided single featuring the songs. The Quartet's sound is shown in full on "Lullaby"--Mulligan makes the bari sax, typically an unwieldly honking horn meant to hold down the bottom, into a graceful dancing giant, while Baker's trumpet darts around him.

By October the quartet was in LA's Gold Star Studios: “Soft Shoe”, a whisper of a track featuring a sublime Mulligan solo that saturates the ear, comes from the first of the sessions, October 15-16. Both tracks can be found here.

Dave Brubeck, who would become the public face of West Coast jazz in 1954, when he was featured on the cover of Time magazine, studied under composer Darius Milhaud at Mills College and formed an octet, a piano trio and at last a quartet in which he first worked with his greatest collaborator, Paul Desmond. Brubeck played loud, dense and heavy chords and favored rhythmically complex works, yet at the same time had a great pop sensibility, covering everything from “The Trolley Song” to various Disney movie numbers; Desmond was far lighter, more lyrical and moody, calling himself “the world’s slowest alto player”, yet his tastes were more rarified than Brubeck's.

"You Go to My Head" is just Brubeck and Desmond, quietly conversing, years before the accolades, campus tours and "Take Five", playing in October 1952 at the Boston club Storyville. Find it here.

Top painting: Marc Chagall's The Green Night.