Marion Harris (1918).

The Versatile Four (1919).

Bessie Smith (1927).

Sophie Tucker (1927).

The Charleston Chasers (1927).

The California Ramblers (1927).

Johnny Dodds' Black Bottom Stompers (1927).

Red Nichols and His Five Pennies (with Jack Teagarden) (1930).

Alphonse Trent Orchestra (1930).

Fats Waller (1930).

Benny Goodman Trio (1935).

Roy Eldridge Orchestra (1937).

Judy Garland (1941).

Cassino Simpson (ca. 1944).

Teddy Wilson Sextet (1944).

Jess Stacy (1944).

Charlie Parker, Lester Young, et al (1946).

Blue Lu Barker (1947).

Al Jolson (1949).

Sonny Stitt (1950).

Sonny Criss (1956).

Dinah Washington (1958).

Jaki Byard (1965).

Nina Simone (1969).

Ray Brown-Herb Ellis Sextet (1974).

Wild Bill Davis (1976).

Count Basie-Oscar Peterson Quartet (1978).

Ralph Sutton (1993).

Andrew Bird (1999).

Fiona Apple (2005).

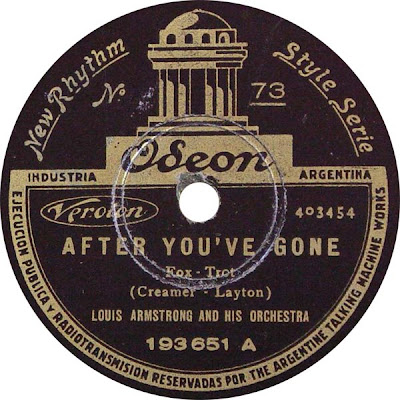

If by this time I haven't conveyed to you by illustration and citation what I mean by an American-sounding song, "After You've Gone" should tell you.

Alec Wilder, American Popular Song.

Posterity was a vaudeville joke audible only to those with front-row seats.

Roberto Bolaño, 2666.

"After You've Gone," like George M. Cohan and knock-knock jokes, was born on the stage, and a trace of greasepaint is found in its lack of shame, or simply in the way the song opens. The singer walks out to center stage, entreating her departing lover (her arms spread wide, or maybe her hands are clasped), and, beyond him, her audience. She begins: "Now listen, honey, while I say."

Now listen. It's a concise command that belies the sentiment of the rest of the song, which quickly veers from desperation to delusion. Quincy Jones once called this type of song a "beg," and said you had to throw in one per album. But as it proceeds, the song goes from a beg to a hopeful, desperate curse. The singer, despite her pleas, realizes in her heart that it's over. Beyond the last wave of self-deceptions, the failed mustered attempts at pride, lies despair and invective: one day you will hurt as much as I do now.

"After You've Gone" is close to a century old and still seems young. Or rather we, as listeners, perhaps at some point age beyond it, consigned to our various measures of contentment or heartache, while it remains whole and unblemished, a hymn of false solace, a pearl of desperate love.

Craftsmen

Turner Layton, ca. 1925

Henry Creamer, a black Virginian (and later New Yorker) born soon after the death of Reconstruction, began working in the theater around 1900, first as an usher, stage manager and "eccentric dancer," later as a songwriter. Creamer, a lyricist, had a number of songwriting partners but only middling success.

In 1916, Creamer met Turner Layton, a pianist fifteen years his younger. Layton, like Jim Europe and Duke Ellington, was a product of the black middle class of Washington DC (Ellington as a kid saw Layton play). He was ambitious and full of melody but had no publishing credits, while Creamer was a wary old pro who had never hit the big time. They had hits as soon as they began collaborating, placing a few songs with Bert Williams.

Sometime in 1917, Creamer and Layton wrote "After You've Gone" for an ailing road show called So Long, Letty. The show failed but the song had hooked audiences. A year later, around the time Al Jolson began to work the song into his shows, Creamer and Layton copyrighted and published it.

The first-ever recording of "After You've Gone" was likely by its composers. Tim Brooks, in his Lost Sounds, discovered that the pair cut a now-lost trial record for Columbia in April 1918, although the title of the song wasn't listed. However, while Columbia rejected the Creamer/Layton disc, it produced the first surviving recording of "After You've Gone" eleven days later, with regular session singers Albert Campbell and Henry Burr (suggesting that Columbia used the Creamer/Layton recording, if it was "After You've Gone," as a template). The Campbell/Burr track, which Brooks accurately describes as being a dreary, late-in-the-day minstrel record, was released in September 1918, and was a decent-sized hit later that year.

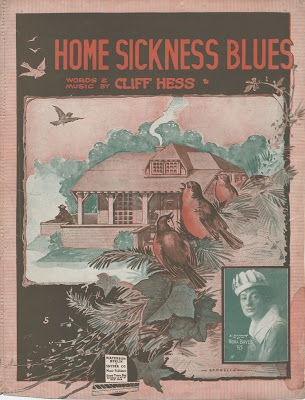

The first masterful recording of "After You've Gone" came in October 1918, when the precocious white blues singer Marion Harris took it on. The move to a solo vocal defined the song, gave it heft: "After You've Gone" can become a dreadful hokey comedy when sung as a duet (e.g., take this dire 1919 duet, a performance that maims Creamer's lyric).

All Kinds of Weather

In fact many would consider "After You've Gone"...the first truly modern popular song because of the way its lyrics focused on personalized emotions rather than abiding by the conventional ballad technique of relating a mini-story.

Wiley Lee Umphlett, The Visual Focus of American Media Culture in the Twentieth Century.

While [Jean] Shepherd would only show his distress in private at the time his marriage was disintegrating, veiled references may have surfaced on his broadcasts. During this period he would sometimes sing on-air an ironic, mock-melodramatic version of "After You've Gone."

Eugene B. Bergmann, Excelsior, You Fathead!: The Art and Enigma of Jean Shepherd.

There's nothing extravagant or novel to "After You've Gone"'s construction: it's a 16-bar verse leading to a 20-bar chorus. The verse often gets dropped, so that many people only know "After You've Gone" as one long repeated chorus with instrumental breaks.

Losing the verse weakens the song, I find: the verse is the preamble, the chorus the constitution. The verses set the stage--the singer tries to make herself heard, uses memories as ransom, begs for another chance, builds up to her declaration. Which is the chorus: an invective, an augury, a wish, a fantasy. Anyone who's heard it once will remember it.

Creamer's lyric has no clever rhyming ("me cryin'/denyin'" is as intricate as it gets), no wordplay. It's how it should be--a more elaborate rhyme structure, a string of metaphors, would ring false. The language is clean and timeless, with the only "period" line being "you'll miss the bestest pal you've ever had" (changed within a decade to "greatest pal").

It's also an early secular gospel song, a pop tune thieving from the hymnal. The chorus is basically a call-and-response, a structure popularized in African-American church services, except here the singer takes both parts:

'Leader': After you've gone

'Chorus': (And left me cryin'!)

'Leader': After you've gone

'Chorus': (There's no denyin'!)

You can hear a preacher's cadences in the vocal line as well, and it wouldn't take much to turn the song back into a gospel tune. Just replace the vagrant lover with a forgiving (or vengeful, depending on your parish) God, and you're halfway there.

Back Where We Started

On Saturday night she and Bill Knowles came to the country club. They were very handsome together and once more I felt envious and sad. As they danced out on the floor the three-piece orchestra was playing After You've Gone, in a poignant incomplete way that I can hear yet, as if each bar were trickling off a precious minute of that time. I knew then that I had grown to love Tarleton, and I glanced about half in panic to see if some face wouldn't come in for me out of that warm, singing, outer darkness that yielded up couple after couple in organdie and olive drab. It was a time of youth and war, and there was never so much love around.

F. Scott Fitzgerald, "The Last of the Belles."

As for the music, Layton's writing is both catchy and quite intricate for the period, particularly in the chorus.

The chorus breaks down into sections: four bars of A (from the first "after you've gone" to "there's no denyin'"), four bars of B ("you'll feel blue" to "you've ever had"), four more of A ("there'll come a time" to "you'll regret it"), the yearning four bars of C ("some-day" to "want me only") and then the coda, four final bars of a truncated A (the last repeat of "after you've gone").

There is a new chord in almost each bar, sometimes two, so it's a rich seam for an improviser to mine. You can hear Charlie Parker, performing "After You've Gone" with Lester Young in 1946, feast on it. The longest static stretch is the seventh and eighth bars in the home key of C ("you'll miss the bestest pal/you've ever had"), which serve as a miniature break: sometimes the band will drop out during it, giving the singer extra power (watch the Fiona Apple performance, for instance--the crowd eats it up). (I'm using The Bessie Smith Songbook as a guide here.)

The song was originally in C major, and the first bar of the chorus is in F, the subdominant, which quickly establishes a sense of yearning impermanence that carries through the rest of the chorus. The poignant heart of the chorus--the C section--is also its most intricate, as it goes Dm/A7/Dm/Dm7-5/C/E7/Am/D7.

After its travels, the chorus comes home again in the last three bars ("after you've gone...after you've gone a-waaay"), which are C/G7/C, suggesting both a resolution and a resignation. He's really going away. Billy Crystal once talked about the time Billie Holiday babysat him. They were watching the end of Shane, and when the boy Crystal called out "come back, Shane!", Holiday just shook her head. "Honey, he ain't ever comin' back."

Establishment

A mixture of reasons prevented him...an inbuilt dislike of cold murder, the feeling that this was not the predestined moment...these, combined with the softness of the night and the fact that the 'Sound System' was now playing a good recording of one of his favorites, "After You've Gone," and that cicadas were singing...said 'No.'

Ian Fleming, The Man With the Golden Gun.

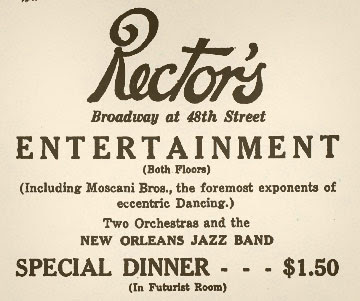

There is a substantial gap between the initial 1918-19 recordings of "After You've Gone," and the burst of interpretations in 1927, after which the song rarely went out of fashion. It's not as though the public had forgotten about "After You've Gone" in the early and mid-'20s--it continued to be performed on stage and was sewn into various medleys. But it wasn't considered a hot property either.

Perhaps a new generation discovered an older model and fell in love with its charms. Or it was simply two women, Bessie Smith and Sophie Tucker, who recorded "After You've Gone" within about a month of each other, and whose discs defined how the piece should be sung. It's arguable that many subsequent interpretations (most obviously Dinah Washington, who did hers on a Bessie Smith tribute album) take their cues from these recordings. If there is a "standard" "After You've Gone," it's here.

With Smith and Tucker's versions as a template, is it fair to say "After You've Gone" is a woman's song at heart? Its male interpreters range from the timid (mousy-voiced Gene Austin in 1930) to joyful braggarts (Al Jolson's self-celebration in 1949), with Jack Teagarden's sly, lazy vocal--in which Teagarden smooths out Layton's melody to better fit his range--as the most charming.

The song's finest interpreters--Harris, Smith, Tucker, Judy Garland, Blue Lu Barker, Ella Fitzgerald, Dinah Washington, Nina Simone and Fiona Apple--all convey the song's power and grace, its measures of rancor and heartache, its futile delusions and its hidden strengths. Each of these records has its own treasures: Garland's frantic attempt at exuberance; Apple's show of determined petulance; Simone's slow boil (she opens the verse almost sleepily, as though she's still letting the blow sink in). "After You've Gone" lends itself to such spectacle and performance: after all, it is the last will and testament of a failed marriage, a desperate coda to a breakup.

True For Many Years

Jack switched to "After You've Gone," doing it loud, tapping a foot. It got so trumpety that, in the middle of putting a hairline on the Y, Roy, afraid his hand might shake, turned and stared burningly at Jack's spine.

John Updike, "The Kid's Whistling."

Jazz players took hold of "After You've Gone" in 1927 (with a prelude in the fascinating, primitive Versatile Four disc from 1919) and have toyed with it ever since. There generally has been some respect granted to "After You've Gone"'s structure: musicians rarely strip it down and refit it in the way they do something like "I Got Rhythm."

The first jazz records from 1927--Johnny Dodds' New Orleans stomp, the society swing of the Charleston Chasers--still include the verse (sometimes after the chorus opens the piece). But soon, by the early '30s, the more harmonically-rich chorus comes to encompass the whole of the song.

Peanuts Holland, opening trumpet solo transcription, Alphonse Trent's "After You've Gone."

Picking a favorite version is impossible: the staggering array of talent in the Red Nichols track, with Teagarden as clown prince; the obscure, brilliant regional bandleader Alphonse Trent, whose "After You've Gone," cut for Gennett Records in Indiana in 1930, opens with a firecracker of a trumpet solo by "Peanuts" Holland, followed by a fine, brassy vocal by Stuff Smith. Or the legendary Benny Goodman Trio track, in which Goodman and Teddy Wilson engage in a battle of wits, while Gene Krupa crashes around behind them.

"After You've Gone" inspired reverence and restraint in some (Coleman Hawkins, Fats Waller, while Art Tatum kept coming back to it over decades), raw exuberance in others (in Roy Eldridge's 1937 recording with his octet, over one four-bar break, Eldridge careers from a high F down to a low G in the space of a few seconds). The song is essentially as old as jazz is, and after a time, it came to be seen as one of the music's founding documents, playing it one of a jazzman's unalienable rights.

Postwar recordings keep to the fairly traditional--there are no truly avant-garde versions of "After You've Gone" that I've found (the wildest version here is by Jaki Byard, who churns "After You've Gone" into a mix with "Strolling Along" during a 1965 concert, going full-tilt, as if a projectionist has cranked a film at three times its normal speed).

In some of the '70s recordings included here, by journeyman players like Wild Bill Davis and Ray Brown and the ageless Count Basie (still fleet at age 74), there's a sense of rediscovery, of sustenance, as though the older "After You've Gone" grows, the more it has to give: it's a replenishing morsel, fit to console us when we are shattered, meant to invigorate us when we are withered.

Here's to its upcoming centennial. Raise a glass to Creamer and Layton, and the dozens upon dozens of geniuses who thankfully have followed their roadmap.

A selected discography:

Pioneers: Marion Harris (18 October 1918; Victor 18509; archive); The Versatile Four (September 1919; Edison Bell Winner 3379; Black String Bands Vol. 3) were Gus Haston (C melody sax, vox, banjoline), Anthony Tuck (banjoline), Charlie Mills (p) and Gordon Stretton (d, perc.).

Canon: Bessie Smith (2 March 1927; Columbia 14197-D; Empress of the Blues Vol. 2); Sophie Tucker (with Miff Mole on trombone) (11 April 1927; OKeh 40837;Last of the Red Hot Mamas).

First jazz discs: The Charleston Chasers (27 January 1927; Columbia 861-D; Vol. 1 1925-1930); The California Ramblers (also went by the name Golden Gate Orchestra) (24 June 1927; Pathe Actuelle 36653); Johnny Dodds' Black Bottom Stompers cut two versions on 8 October 1927 (Brunswick 3568; Definitive Dodds).

Master jazz: Red Nichols and His Five Pennies (2 Feb 1930; Brunswick 4839; 1929-1930): a mind-blowing supergroup, with Jack Teagarden (vox, tb), Charlie Teagarden, Nichols, Tommy Thunen (cornet), Glenn Miller (tb), Benny Goodman (cl), Jimmy Dorsey (cl/altos), Manny Klein (tpt), Babe Russin (t/sx), Adrian Rollini (bs/sx), Jack Russin (p), Weston Vaughan (g), Jack Hansen (b), and Gene Krupa (d)!

Alphonse Trent (5 March 1930; Gennett 7161; Richmond Rarities), with Herbert “Peanuts” Holland, Chester Clark, Irving Randolph, George Hudson (t), Leo “Snub” Mosely (tb), James Jeter, Charles Pillars, Lee Hilliard (as), Hayes Pillars (ts, bars), Leroy “Stuff” Smith (v, vox), Eugene Crooke (bjo, gtr), Robert “Eppie” Jackson(b), A.G. Godley (d).

More mastery: Fats Waller (21 March 1930; Victor 22371; Compete Victor Piano Solos); The Goodman Trio (Goodman, Krupa, Wilson)'s first-ever studio recording (13 July 1935; Victor 25115;Complete Small Groups) was two takes of "After You've Gone"--here's the second.

Roy Eldridge's Orchestra (28 January 1937; Vocalion 3458; Little Jazz): Scoops Carry, Joe Eldridge (alts); Dave Young (tens); Teddy Cole (p); John Collins (g); Truck Parham (b); Zutty Singleton (d); Gladys Palmer (vox); Judy Garland's standard version is from the 1941 MGM film Ziegfeld Girl.

Unknown soldiers: Cassino Simpson's take, ca. 1942-1944, was likely taped during his stay at Elgin Mental Hospital--released as a limited "gift" 78 record (UP 102) in 1947; Jess Stacy's piano/drums duet with Specs Powell was recorded for Commodore on 25 November 1944 but not released until decades later (1944-1950).

Bop era versions: Teddy Wilson's Sextet (c. Nov 1944; Standard Q208; After You've Gone): Red Norvo vibes, Charlie Shavers (tp), Remo Palmieri (g), Al Hall (b), Specs Powell again (d); Parker and Young' s JATP concert also featured Willie Smith (altos), Killian Howard McGhee (t), Arnold Ross (p), Billy Hadnott (b) and Lee Young (d). (28 January 1946; released in two parts as Mercury 11041; Jazz at the Philharmonic 1946.)

Blue Lu Barker's take was recorded live 31 May 1947, by Rudi Blesh (Jazzin' the Blues Vol. 5); Jolson's 1949 "After You've Gone" was released as the soundtrack to Jolson Sings Again, the dud sequel to The Jolson Story (Decca 9-24683; later on The Singing Detective).

Hard bop: Sonny Stitt Septet (8 November 1950; Prestige 727; later on Stitt's Bits): Bill Massey (tp), Matthew Gee (tb), Stitt (ts), Gene Ammons (bars), Junior Mance (p), Gene Wright (b) ,Wes Landers (d); Sonny Criss Quartet (31 July 1956, LA; Imperial 9020; Go Man!): Criss (altos), Sonny Clark (p), Leroy Vinnegar(b) and Lawrence Marable (d).

Freedom: Jaki Byard Quartet (15 April 1965, rec. at "Lennie's On The Turnpike" in West Peabody, MA; The Last From Lennie's): Joe Farrell (ts, ss, fl, d), Byard (p), George Tucker (b) and Alan Dawson (d, vib) .

Later divas: Dinah Washington (7 January 1958, Chicago; Dinah Sings Bessie Smith, MG 36130) with Fortunatus Fip Richard (tp), Julian Priester (tb), Eddie Chamblee (ts), Charles Davis (bars), Jack Wilson (p), Robert Lee Wilson (b), James Slaughter (d), arr. by Robare Edmonson; Nina Simone, rec. live ca. 1969, on a few odd compilations like Gin House Blues.

Revivals: Ray Brown-Herb Ellis Sextet (August 1974, Concord Jazz Festival, CA; After You've Gone (Concord Jazz 6006), later on Concord Jazz Heritage Series): with Ellis (g), Brown (b), Harry "Sweets" Edison (t), Plas Johnson (tenors), George Duke (p) and Jake Hanna (d); Wild Bill Davis (21-22 January 1976, Paris; All Right, OK, You Win) with Billy Butler, Oliver Jackson and Eddie "Lockjaw" Davis.

Count Basie-Oscar Peterson Quartet, (21-22 February 1978; Count Basie Meets Oscar Peterson--the Timekeepers), with John Heard (b) and Louis Bellson (d); Ralph Sutton (Live at Maybeck Recital Hall, 1993).

New kids: Andrew Bird (live in Austin, TX, 19 March 1999; complete show here). And Fiona Apple's performance, from the now-deceased Virgin Megastore in NYC, Sept. 2005, shows that she needs to do an album of standards, stat.

Next: Armistice (war is over if you want it)