French woman working at munitions factory, ca. 1915-1916

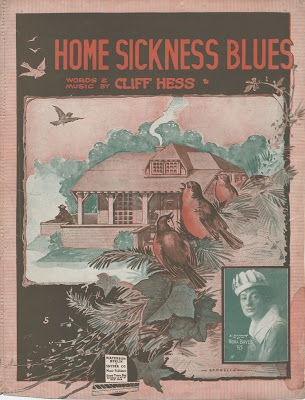

Nora Bayes, Homesickness Blues.

Marion Harris, Paradise Blues.

The Versatile Four, Circus Day In Dixie.

Ciro's Club Coon Orchestra, I Can Dance With Everybody Except My Wife.

Tristan Tzara, Marcel Janco and Richard Huelsenbeck, L’Amiral Cherche Une Maison à Louer.

I see men arising and walking forward and I go forward with them, in a glassy delirium wherein some seem to pause, with bowed heads, and sink carefully to their knees, and roll slowly over, and lie still. Others roll and roll, and scream and grip my legs in uttermost fear, and I have to struggle to break away, while the dust and earth on my tunic changes from grey to red...

And I go on with aching feet up and down across ground like a huge ruined honeycomb, and my wave melts away, and the second wave comes up and also melts away, and then the third wave merges into the ruins of the first and second, and after a while the fourth blunders into the remnants of the others, and we begin to run forward to catch up with the barrage, gasping and sweating, in bunches, anyhow, every bit of the months of drill and rehearsal forgotten, for who could have imagined that the "Big Push" was going to be this?

Henry Williamson, recalling 1 July 1916 on the Somme.

The length of this horrible war is most depressing. I really think it gets worse the longer it lasts.

Queen Mary, letter to Lady Mount Stephen, November 1916.

Nora Bayes' "Homesickness Blues" is her finest record, and while it's not a 'proper' 12-bar blues, everything about it--the weary melody the winds and brass play in the opening bars (and which recurs as a motif), the quiet melancholy flavor of Bayes' vocal, the relaxed beat, the lack of minstrel buffoonery--marks it as a truly modern record, a face card shuffled ahead in the deck.

Allen Lowe: [Bayes'] 1916 recording pre-dates the accepted classic era of blues and jazz recordings, but it tells us that the sound of it was already well circulated by the time record companies caught up with the fact of its general, bi-racial popularity...'Homesickness Blues' has no straining for effect, silly slurring or shallow posturing. What it does have is a vocal with powerful presence and confident technique, including a beautifully executed glissando of the type that later jazz singers would turn into a cliche, and which Bayes executes without vanity.

Recorded 4 May 1916 and released as Victor 45100; in this archive. Cliff Hess, who wrote the song, started out by playing piano on Mississippi riverboats and in the '10s worked as Irving Berlin's secretary.

Royal Irish Rifles on the Somme, July 1916

Honey don't play me no opera

play me some blue melodies

I don't care nothing 'bout 'Carmen'

when I hear those harmonies

Marion Harris' "Paradise Blues" finds a 20-year-old first-edition flapper singing a blues anthem by the bard of Basin Street, Spencer Williams, and going to town with it.

Harris is one of the first white female singers to effectively convey a blues and jazz sensibility on record, and she would only get more inspired over the next decade. She left Victor Records in 1920 because they wouldn't let her cut "St. Louis Blues," which she could deliver impressively--"She sang blues so well that people sometimes thought that the singer was colored," W.C. Handy said of Harris.

Spencer Williams was born in New Orleans in 1889 and grew up in the town's red light district, living for a time as the ward of the madam Lulu White, who ran the Mahogany Hall brothel (Williams later would write "Mahogany Hall Stomp" (watch this, seriously) in tribute). By the late '00s Williams was in Chicago, working as a Pullman porter and playing piano in nightclubs, where he met the song publisher Clarence Williams (no relation). They formed a partnership and moved to New York in 1918. By then, Spencer had already struck gold with our Miss Harris, who had made his "I Ain't Got Nobody" and "Paradise Blues" hits.

Recorded 17 November 1916 and released as Victor 18152; find in this extensive Harris archive.

In September 1916 James Reese Europe joined the 15th Infantry Regiment of the New York National Guard. By this point, many in the United States knew they were entering the war: it was simply a matter of when (of course, this was just as Woodrow Wilson was campaigning for re-election under the slogan "He Kept Us Out of War").

Europe, like many African-Americans, hoped the war could serve as a catalyst--a way for professional advancement, a chance to demonstrate bravery, dignity and competence to a racist society. Nothing would be the same after the war, the thought went. It was true--but only after the Second World War. After the First, nothing much changed except the KKK revived.

Before Europe went overseas, his former bandmates, his arrangements and his influence served as advance guards. Veterans of Europe's old Clef Club Orchestra had flooded into London, finding a ready audience of soldiers on leave and bored/lonely young women ready to hear hot music.(Also, many London-based German musicians had been thrown out of work.) One group was the Versatile Four, who played at Murray's Club on Beak Street in Soho.

(Murray's Club has a storied history--it was here during WWI that British military officials met to develop their new weapon, the tank, and Christine Keeler worked as a hostess at a later incarnation of the club in the early '60s.)

"Circus Day in Dixie" was one of the Four's first (and only) recordings, a piece dominated by Charlie Johnson's drum kit. With Gus Haston on banjo and also hollering a vocal, Tony Tuck (banjo) and Charlie Mills (piano). "Enjoy yourself!" Haston yells at one point, but the track is so fine no one needed his encouragement. Recorded 3 February 1916 in Hayes, Middlesex, UK, and released as HMV C-645; on Stomp and Swerve or in this archive.

Former slaves reunion, 1916 (Shorpy)

I don't know what one would do to keep one's spirits if it weren't for the theatres and restaurants, and the little dances, with Ciro's band to bang away till breakfast time. The coon music, by the way, isn't getting depressed at all--in fact, it's madder than ever.

Gossip columnist in the Tatler, September 1916.

Another expat was Dan Kildare, who we last met working for Joan Sawyer as her bandleader at the Persian Garden in New York. From 1915 to 1917, Kildare and his band played in London at Ciro's Restaurant, a swank Orange Street club that was decorated in Louis XIV style and featured a sliding roof and a dance floor on springs. Kildare's group also played society gigs, including a garden party at Grosvenor House attended by Winston Churchill and Lord Asquith. (From Tim Brooks' Lost Sounds.)

The British branch of Columbia Records soon signed Kildare and christened his band with the gruesome name "Ciro's Club Coon Orchestra." The first sessions, in August 1916, were cuts of popular show tunes, including Raymond Hitchcock's "I Can Dance With Everybody Except My Wife," included here--the tracks, possibly due to poor engineering, are overwhelmed by the banjo players, so that Kildare's piano is barely audible and the drums sound like they're in another room.

The Orchestra, on this track, was Kildare (p), Walter Kildare (vox), Vance Lowry (banjo), Ferdinand Allen (banjoline), Sumner "King" Edwards (b) and Hugh Pollard (d); recorded in London and released as Columbia 2703; on Ragtime to Jazz Vol. 4.

Hugo Ball, 1916

DADA! DADA! DADA! DADA!

On Saturday night, the 5th of February 1916, in Zurich, the Cabaret Voltaire opened.

Dada has been mixed up with an art movement though it has nothing to present as an art movement if you think of Cubism, of Impressionism, or whatever, these are all problems of form, of color, of something that is shown or devised or has the aim of being a work of art; now this we didn't have at all. We had practically nothing except what we were.

Richard Huelsenbeck, 1971.

The Cabaret Voltaire was a six-piece band. Each played his instrument, i.e., himself.

Hans Richter, 1964.

Total pandemonium. The people around us are shouting, laughing, and gesticulating. Our replies are sighs of love, volleys of hiccups, poems, moos and the miaowing of medieval Bruitists. [Tristan] Tzara is wiggling his behind like the belly of an Oriental dancer, [Marcel] Janco is playing an invisible violin and bowing and scraping. Madame [Emmy] Hemmings, with a Madonna face, is doing the splits. Huelsenbeck is banging away nonstop at the great drum, with [Hugo] Ball accompanying him on the piano, pale as a plaster dummy.

Hans Arp, describing lost Janco painting of the Cabaret Voltaire, 1948.

This recording of Richard Huelsenbeck, Tristan Tzara and Marcel Janco's "simultaneous poem" "L’amiral cherche une maison à louer"("the admiral looks for a house to rent") demonstrates how the piece was performed on stage on its debut in March 1916. It's a poem that can only exist as a performance, as being three separate verses delivered at once, it's impossible to read on the page. Performed by the Italian trio Excoco (Hanna Aurbacher, Theophil Maier and Ewald Liska); on Futurism and Dada Reviewed.

Next: The Day of the Women's Death Battalion

No comments:

Post a Comment