Marcel Proust on his deathbed (photo by Man Ray).

Lizzie Miles, She Walked Right Up and Took My Man Away.

Paul Hindemith, Suite '1922': Ragtime.

Edna St. Vincent Millay, Recuerdo.

George Antheil, Airplane Sonata (As Fast As Possible).

Kid Ory's Sunshine Orchestra, Society Blues.

Husk O'Hare's Super Orchestra of Chicago, San.

Friars Society Orchestra, Tiger Rag.

Trixie Smith and the Jazz Masters, My Man Rocks Me (With One Steady Roll).

According to Ezra Pound, the Christian era ended on October 30, 1921, when James Joyce wrote the final words of Ulysses. Actually, Pound had proclaimed the end of the Christian era at least once before, but this time he was serious enough to propose a new calendar in which 1922 became Year 1 of a new era...

This dramatic advent of a new literature was at least part of what Willa Cather had in mind when she complained, "The world broke in two in 1922 or thereabouts."

Michael North, Reading 1922.

Steiner, Lollipop.

Lizzie Miles was born on Bourbon Street as the 19th Century was packing up; she sang for King Oliver, Kid Ory and Fats Waller, plugged songs for Clarence Williams, toured with fly-by-night circuses, medicine shows and vaudeville productions (including one the boxer Jack Johnson arranged), played and cut records in Chicago, New York and Europe. She was a rolling stone, an embodiment of black music and culture in the first third of the past century.

One of her first records, "She Walked Right Up and Took My Man Away," is more stagy and pop-oriented than the blues recordings of Mamie Smith and (starting in the following year) of Bessie Smith, but there's still a grit in Miles' singing, in the way she charges ahead of the beat, and her power's undeniable.

Recorded 24 February 1922 and released as OKeh 8031; on Complete Recorded Works Vol. 1.

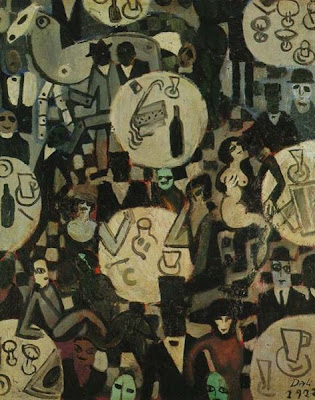

Dali, Cabaret

In 1940, the German composer Paul Hindemith (then living in Switzerland in exile--Goebbels had denounced him as an "atonal noisemaker," plus Hindemith's wife was Jewish) wrote to a friend that he didn't want to reprint what he called "that awful Suite '1922'", adding that "it depresses an old man rather seriously to see that the sins of his youth impress the people more than his better creations." A lament that many older men likely have said in their time.

But back when Hindemith was a sinning youth, an ambitious working-class kid from Hanau who played violin in dance bands and thumped a bass drum in a military band during WWI, works like Suite '1922' showcased his brashness, irreverence and raw energy. As Alex Ross wrote, "the archetypal Hindemith piece takes the form of a fast, furious off-kilter march, with fanfares in multiple tonalities and bass lines bent off course. The music is intense, but it does not take itself particularly seriously."

Suite '1922' For Piano, mainly composed in its title year, was Hindemith's attempt to parody and upend the new types of pop music surfacing in Europe during the postwar years--ragtime, foxtrots, jazz, blues. It's a five-part suite, with movements entitled "Shimmy," "Boston" and the closing section "Ragtime" in which the performer is instructed to "look at the piano as a percussion instrument and act accordingly."

The "Ragtime" movement of Suite '1922', op. 26, is performed here by Jan Marcol on Jazz Inspired Popular Music.

Prince Hirohito and Empress Teimei take the air with Edward, Prince of Wales

Interlude: The Class of 1922

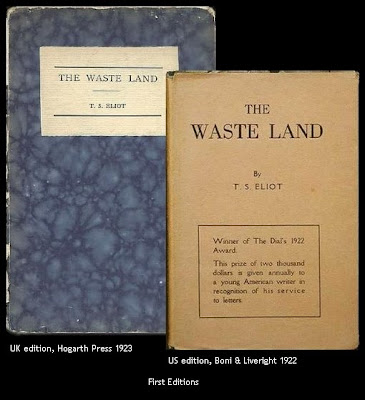

Datta: what have we given?

My friend, blood shaking my heart

The awful daring of a moment’s surrender

Which an age of prudence can never retract

By this, and this only, we have existed

Which is not to be found in our obituaries

Or in memories draped by the beneficent spider

Or under seals broken by the lean solicitor

In our empty rooms...

T.S. Eliot, The Waste Land: V. "What the Thunder Said."

Bronze by gold heard the hoofirons, steelyrining imperthnthn thnthnthn.

Chips, picking chips off rocky thumbnail, chips. Horrid! And gold flushed more.

A husky fifenote blew.

Blew. Blue bloom is on the

Gold pinnacled hair.

A jumping rose on satiny breasts of satin, rose of Castille.

Trilling, trilling: I dolores.

Peep! Who's in the... peepofgold?

Tink cried to bronze in pity.

And a call, pure, long and throbbing. Longindying call.

Decoy. Soft word. But look! The bright stars fade. O rose! Notes chirruping answer. Castille. The morn is breaking.

Jingle jingle jaunted jingling.

Coin rang. Clock clacked.

Avowal. Sonnez. I could. Rebound of garter. Not leave thee. Smack. La cloche! Thigh smack. Avowal. Warm. Sweetheart, goodbye!

Jingle. Bloo.

Boomed crashing chords. When love absorbs. War! War! The tympanum.

James Joyce, Ulysses: "overture" to the musical "Sirens" chapter.

Fritz Lang, Dr. Mabuse, der Spieler.

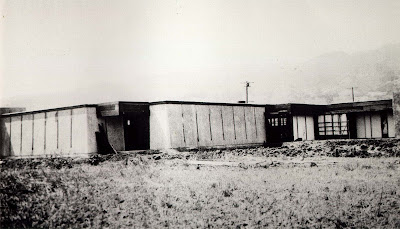

Each house needs to be composed as a symphony, with variations on a few themes.

Rudolph Schindler, the Kings Road House, Hollywood.

The future of the world lies in the vibration of its people. The environment of the machine has already become a spiritual thing...For the great mass of us the war has killed illusion and sentimentality...Hence the birth of the Music-Mechanists.

George Antheil, Second "Airplane" Sonata, (here performed by Marthanne Verbit).

In other words, there is a series of phenomena of great importance which cannot possibly be recorded by questioning or computing documents, but have to be observed in their full actuality. Let us call them the imponderabilia of actual life. Here belongs such things as the routine of a man's working day, the details of his care of the body...the tone of conversational life around the village fires, the existence of strong friendships or hostilities, and of passing sympathies and dislikes between people, the subtle yet unmistakable manner in which personal vanities and ambitions are reflected in the behaviour of the individual and in the emotional reactions of those who surround him...

Bronislaw Malinowski. Argonauts of the Western Pacific.

We hailed "Good morrow, mother!" to a shawl-covered head,

And bought a morning paper, which neither of us read;

And she wept, "God bless you!" for the apples and pears,

And we gave her all our money but our subway fares.

Edna St. Vincent Millay, "Recuerdo," collected in A Few Figs From Thistles.

The band played in the Moorish kiosk. Number nine went up on the board. It was a waltz tune. The pale girls, the old widow lady, the three Jews lodging in the same boarding–house, the dandy, the major, the horse–dealer, and the gentleman of independent means, all wore the same blurred, drugged expression, and through the chinks in the planks at their feet they could see the green summer waves, peacefully, amiably, swaying round the iron pillars of the pier.

But there was a time when none of this had any existence (thought the young man leaning against the railings). Fix your eyes upon the lady’s skirt; the grey one will do—above the pink silk stockings. It changes; drapes her ankles—the nineties; then it amplifies—the seventies; now it’s burnished red and stretched above a crinoline—the sixties; a tiny black foot wearing a white cotton stocking peeps out. Still sitting there? Yes—she’s still on the pier. The silk now is sprigged with roses, but somehow one no longer sees so clearly. There’s no pier beneath us. The heavy chariot may swing along the turnpike road, but there’s no pier for it to stop at, and how grey and turbulent the sea is in the seventeenth century! Let’s to the museum. Cannon–balls; arrow–heads; Roman glass and a forceps green with verdigris. The Rev. Jaspar Floyd dug them up at his own expense early in the forties in the Roman camp on Dods Hill—see the little ticket with the faded writing on it.

Virginia Woolf, Jacob's Room.

Kid Ory's Sunshine Orchestra was the first black New Orleans jazz group to record, albeit in Los Angeles. The trombonist Ory had wound up in California on doctor's orders (he was told a dry climate would help him). He soon assembled Ory's Original Creole Jazz Band (sometimes called Ory's Brown-Skinned Babies) and was playing around the state.

Benjamin "Reb" Spikes and Johnny Spikes were Okie brothers who ran a theater in Muskogee (in 1911, they hired Jelly Roll Morton for a time). By the end of the '10s they had moved to LA, opened the only record store in the city that sold records by black musicians (Reb Spikes later recalled how "wealthy Hollywood people would drive up in long limousines and send their chauffeurs in to ask for “dirty records'") and soon were running jazz shows and looking to cut their own records.

The Spikeses asked Ory and his band to cut four sides for their start-up label, Sunshine. Everyone was green when it came to recording--Ory showed up at the session in a tuxedo, figuring that's what you wore on such occasions; the Spikeses later lost some of their masters when the wax melted during a long drive across the desert.

These first Ory sides aren't the typical frenetic wailing-and-honking New Orleans jazz as popularized by the Original Dixieland Jazz Band, but rather are smooth, precise templates: documents of a vibrant and maturing music. Recorded July 1921 (?)* and released (as both the Sunshine Orchestra and Spike's Seven Pods of Pepper Orchestra) as Sunshine 3003 and Nordskog 3009 c/w "Ory's Creole Trombone"; on Kid Ory & His Creole Jazz Band.

* While many jazz histories and discographies have the date of the first Ory recordings as June 1922, this article by Floyd Levin states otherwise--that it was a year earlier. The source is Robert Nordskog, son of Arne Nordskog, who engineered the recordings.

Perret, Study for Tower Blocks for Paris.

Husk O'Hare was a promoter and a hustler as much as he was a bandleader. He grew up in Chicago's West Side (his real name was Anderson O'Hare, but as he was a chubby guy, "Husk" soon stuck), served in the Army during the war and by 1920 was working with another promoter, Sol Weisner, to try to corner the growing Chicago jazz market. At their peak, O'Hare and Weisner were booking as many as 42 different bands at once. O'Hare had a taste for self-promotion (most notably in the large flashing sign he had installed on the roof of his Monroe St. office), and soon started running his own bands--Husk O'Hare's Campus Serenaders, Husk O'Hare and His Greatest Band or, as featured here, Husk O'Hare's Super Orchestra of Chicago.

His main requirement for his players was that they be young and willing to work often and cheap. Many jazz players grew to resent O'Hare, who had a habit of being named bandleader of sessions he had only booked (The New Orleans Rhythm Kings formed out of a group of disgruntled O'Hare players (see below)) but O'Hare wasn't a fraud--he had a legitimate taste for jazz, and likely was the person who sold Gennett Records on taking on the King Oliver band and its new trumpeter, Louis Armstrong. (Much of this information is from Charles A. Sengstock's That Toddlin' Town.)

Tracks like O'Hare's "San" show jazz arranging coming into its own--rather than the set constrictions of ragtime, there's a smoother, logical flow to the arrangement, with an extended written section broken up by possibly improvised jazz breaks. Recorded December 1922 and released as Gennett 5009-A; on Ragtime to Jazz 2.

O'Hare wound up credited as an arranger on the Friars Society Orchestra recording of "Tiger Rag," though O'Hare apparently was nowhere near the studio at the time. Friars Orchestra would soon change its name to the New Orleans Rhythm Kings and become one of the essential jazz bands of the early '20s--its members included the Sicilian clarinet player Leon Roppolo, who would sometimes hurl his clarinet against the wall during a gig when he got in a temper.

Recorded 30 August 1922 and released as Gennett 4968; on New Orleans Rhythm Kings 1922-1923.

Strand, Double Akeley, New York.

Finally, a signpost for a future destination: Trixie Smith's "My Man Rocks Me (With One Steady Roll)." Recorded ca. September 1922 and released as Black Swan 14127; on Trixie Smith Vol. 1.

Lately in Bowieland: DB leaves home, digs everything, gets class conscious, grows sad and old.