Billie Holiday (with Lester Young, et al), Fine and Mellow.

Billie Holiday, Comes Love.

Count Basie Orchestra (with Lester Young), Polka Dots and Moonbeams.

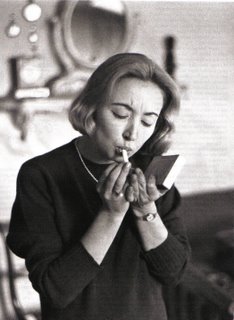

Every lost friendship is tragic in its way, but that of Billie Holiday and Lester Young was especially so, although marked with one last moment of grace.

Billie and Lester were the young giants of the 1930s--Young with the Count Basie Orchestra, where his light, numinous tenor saxophone playing was a contrast to the deep, robust sound crafted by Coleman Hawkins; Holiday with Teddy Wilson's group, where she could clad the most mediocre pop song in genius. Holiday and Young often worked together then--she allegedly gave him the nickname "Prez" (short for "President of the tenor saxophone") and he called her Lady Day.

Distance and hard time intervened. By the mid-'50s, both were in battered shape: years of addiction and rough living (both spent time in prison in the '40s) had taken a vicious toll on them. They had become estranged, years before, for obscure reasons. Prez, an alcoholic, was said to have been upset over Holiday's drug use, but they simply might have grown used to not seeing each other, in the way that many friendships die.

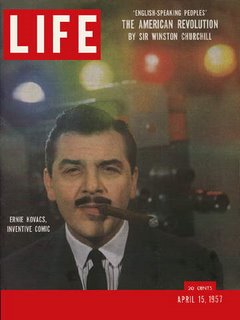

But on December 8, 1957, Young and Holiday were in the same studio together, to film a TV special called "The Sound of Jazz."

Their reunion came on "Fine and Mellow," Holiday's own composition. The take recorded for the accompanying LP (on Dec. 5) was a bit restrained, but when the cameras rolled for the live broadcast three days later, it was the sort of performance that justifies life. After Billie sings, Ben Webster, all class, comes in for a solo chorus. Then Young, who had been the only player sitting, jolts up, startling the cameraman, who loses him for a moment. Young looks, to be honest, quite weary, but he starts his solo with confidence, and he offers a gemstone of melody, thirty-seven seconds in length, a solo "so solidly constructed that, after you've heard it a couple of times, it becomes part of your nervous system, like the motor skills required to ride a bicycle" (Gary Giddins).

Billie returns, escorted by Doc Cheatham on trumpet; Vic Dickenson follows on trombone and Gerry Mulligan, the sole representative of the postwar generation, delivers a chorus on baritone sax. After another Holiday verse, Coleman Hawkins (who was everywhere in '57, apparently) comes in, low and dignified. Cheatham gets the longest solo, then Billie rounds it out.

But listening to the track gives you only half the story. Much of the joy of the performance lies in watching Holiday's interaction with the players, who surround her in a semi-circle, like courtiers. She considers each solo as if it were a proposal, shaking her head, smiling, grooving. And when the camera cuts to Billie while Young plays, as we watch her smile, nod, and see her features dance with remembrance--well, it's hard to remain dry-eyed sometimes. The whole performance is a valedictory for swing, for the life and gifts of Holiday and Young. Enough words: watch.

The Sound of Jazz soundtrack unfortunately features the rehearsal version of "Fine and Mellow," which is shorter, inferior and has different players than the aired version. The real McCoy--the superior TV take from Dec. 8--is on Billie Holiday's Ken Burns Jazz compilation.

Holiday also recorded some fine tracks on her own that year, my favorite being "Comes Love." Ever since its introduction by a hillbilly comedienne in the 1939 musical Yokel Boy, "Comes Love" had been treated as a novelty, performed generally as an uptempo rhumba (Al Young). Holiday and her band, however, slowed it down, tamed the rhythm to 4/4 and made it sultry, with a biting wit. Holiday's late Verve years are controversial--sometimes her singing is harsh, sometimes the arrangements drown her--but this track is a marvel.

"Comes Love" was recorded in Hollywood on January 4, 1957. With Harry "Sweets" Edison (t), Ben Webster (tenor sax), Barney Kessel (g), Red Mitchell (b) and Alvin Stoller (d). On Body and Soul.

And one of Young's last great moments is found on Count Basie's "Polka Dots and Moonbeams," which was recorded at the Newport Jazz Festival on July 7, 1957. The Basie band at this time included Frank Foster, Frank Weiss (tenor sax), Benny Powell (tb), Eddie Jones (b), and Jo Jones (drums). The introduction is by John Hammond, who had the sort of classic New York accent that seems to be a lost art.

After the full band announces him, Young begins his solo, which goes for the remainder of the performance. It's a dreamsong, a performance almost gossamer in its delicacy and grace, yet surging with power and incisive character. On Count Basie at Newport.

On March 15, 1959, Lester Young died alone in New York, after a European tour in which he essentially drank himself to death. On the way to Young's funeral, Holiday told Leonard Feather "I'll be the next one to go." Four months later, she left.