Tom Robinson Band, 2-4-6-8 Motorway.

The Modern Lovers, Roadrunner.

Blue Flamers, Driving Down the Highway.

Bond glanced in his driving mirror. Well, well! The little Triumph was only feet away from his tail. How long had she been there? Bond had been so intent on following the Rolls that he hadn't glanced back since entering the town. She must have been hiding up a side street...Bond stopped abruptly in front of a butcher's shop. He banged the gears into reverse. There was a sickening scrunch and tinkle. Bond switched off his engine and got out.

He walked round to the back of the car. The girl, her face tense with anger, had one beautiful silken leg on the road. There was an indiscreet glimpse of white thigh. The girl stripped off her goggles and stood, legs braced and arms akimbo. The beautiful mouth was taut with anger.

The Aston Martin's rear bumper was locked into the wreckage of the Triumph's lamps and radiator grille. Bond said amiably, "If you touch me there again you'll have to marry me."

The words were hardly out of his mouth before the open palm cracked across his face.

Ian Fleming, Goldfinger.

About two years ago, I began driving again. I had lived in Boston and New York for a decade and a half, and sometime during those years I was reduced in rank to an irregular, a reservist, driving only whenever I visited my parents, so that taking their car down to the grocery store became a tremendous novelty. At some point driving became something that other people did, like sky-diving or having children.

It wasn't always so. I had spent years behind the wheel--I got my driver's license at 16 (having failed the test once, when I panicked and couldn't put the car in reverse, and the old man grading me said, "Switch it off! You're done!" with joy in his voice) and I drove every day to school, to work, to kill time. The summit of this life was the summer of '91, during which I drove an hour each way to my job in Mystic, then, to stave off boredom, drove around my hometown every evening, drove to Boston sometimes on weekends. I even took to eating lunch in my car, making it through "The Portable Faulkner" over one hot month.

Yet when I returned to the road, at age 33, I found that something was off. While the rudiments of how to work a car and my Irish grandmother driving habits (I tend to look both ways about five times until I pull out onto a main road) returned easily enough, my attitude had withered.

Well, it's mainly the highway. Driving on the highway, especially in the car-choked interstates that link New York with Connecticut, has become slightly horrific. Maybe it's the cars riding me in the right lane for going only ten miles above the speed limit, or having to drive over decayed bridges and cracked lanes, or routinely being near-blindsided by trucks. The general feeling is that one is wandering through a shooting range where distracted, stupid people are randomly firing at you. So sometimes when driving on the highway, I find my palms sweat, my legs tense up, my breathing grows irregular--I feel like a spring coiled too tight. It's not good.

Maybe it's just the thought of the highway itself--featureless, endless, lifeless. There is a long sloping decline in the middle of Connecticut, where you can see the highway roll out before you for flat miles ahead, which I find a bit heartbreaking. All those people heading in the same direction, generally the only person in their car, passing and being passed, with no way off but the breakdown lane.

Yet there also are many times, driving on narrow country roads, or even in the winding maze of a city (weirdly, I don't mind city driving at all) when I find driving euphoric. And flooring the gas pedal, zipping over a hill, is the easiest legal elation still available to us. So more and more, I take back roads to get anywhere, sometimes adding a half-hour or so to my travel time. It is likely a way to cheat a growing panic disorder on my part; it is also, I'd like to believe, a small act of insurrection against the way our life has been laid out.

So, as a counterweight, here are three celebrations of life on the highway:

The Tom Robinson Band's "2-4-6-8 Motorway" was the TRB's first single. Always loved Danny Kustow's guitar on this track. Released as EMI 2715 c/w a cover of "I Shall Be Released" in late 1977; on Rising Free. A rocking performance. Tom Robinson's Guardian blog.

First thought: "I can't include 'Roadrunner.' Too obvious, and everyone's sick of it." Second thought: "How the hell can I not include 'Roadrunner'?"

On the slim chance you've never heard the song before, enjoy--it's one of the best things ever. Recorded by Jonathan Richman, Jerry Harrison, Ernie Brooks and David Robinson in Los Angeles in April 1972, and released four years later on Modern Lovers, which is not in print in the US.

Finally the Blue Flamers' "Driving Down the Highway," a fine piece of postwar Nashville R&B, sung by Bob Elliot, with the rest of the band unknown (the only bit of information to surface is that the saxophonist was named "Carl"). Released in 1954 as Excello 2026 c/w "Watch On." On the out-of-print Excello Story Vol. 1.

Internal Combustion

Junior Wells, I Need Me a Car.

Clifford Hayes' Louisville Stompers, Automobile Blues.

Lightnin' Hopkins, Automobile.

The Dixie Hummingbirds, Christian's Automobile.

The Divine Comedy, Your Daddy's Car.

Nothing has spread socialistic feeling in this country more than the use of the automobile...to the countryman they are a picture of the arrogance of wealth, with all its independence and carelessness.

Woodrow Wilson, address to the North Carolina Society, 1906.

The greatest instrument of American joy, the automobile, has in twenty years shifted regulation in a hundred directions.

Herbert Hoover, Addresses Upon the American Road, 1936.

Frank, Drive.

Driving a car is freedom at its most conformist. Driving is addictive, expensive and is not, in the long run, good for our bodies or our world, but as Elaine Stritch once sang, "Jesus Christ, is it fun."

While cars can be alluring, intoxicating objects, the culture built to service and worship them is often banal and irrational. And yet, there is something miraculous about driving. If you have the time, and enough money for gas, you could get in a car in Providence and drive to the Pacific Ocean. Or the Panama Canal. Or you could wake up in Normandy and, after a day's drive, sleep in Monaco. Or you could wake up in China and sleep somewhere else in China.

Driving is the realm of the present tense. Driving has only been around for a century, but it now seems like a permanent condition of the human race. For most of us alive today, as Neil Hannon sings in "Your Daddy's Car," we've been driving since the day we were born: the day you get your license is the closest thing left to a rite of adulthood, and on the day the state or your family takes your license away, you take one big stride closer to death.

Driving is isolating; driving grants you access to society. I still feel like an idiot whenever I open my car hood, like a Neanderthal sitting in front of a PC, but slowly, the more I go to garages and hardware stores, and talk about tire pressure and oil changes and inspections and mileage, the more accepted I feel. I got the car inspected last week, and whenever the mechanic would make an aside to me ("those back wheels aren't doin' any of the work, they're just along for the ride") I would beam and nod, like a newly-minted citizen voting for the first time.

And music is the automobile's finest advocate, its greatest cultural achievement. If honky-tonk was made to be heard over the din of a Saturday night bar, rock & roll was, from its earliest hours, music made for a car (thus you have John Fogerty playing new Creedence tracks on his car stereo before releasing them, to be sure the mix sounded right).

A number of thoughts on the automobile:

Junior Wells' "I Need Me a Car" sums up a still-relevant dilemma for most of us--if you don't have a car, forget about getting a date. The track ends with Wells heading down to the car dealership, under protest. Guitar solo is likely by Wells' regular partner Earl Hooker, but I'm not certain. Released in 1962 as Chief 7038 c/w "I Could Cry"; on Messin' With the Kid.

The Louisville Stompers were one of several jug bands led by the violinist Clifford Hayes in the late '20s. "Automobile Blues," recorded 6 February 1929, features the great jazz pianist Earl Hines, who is barely audible underneath layers of jug bass, fiddle, and clattering guitar; the track has a vocal so wavering and distorted that it borders on glossolalia. Released as Victor 23407 c/w "Shady Lane Blues." On Clifford Hayes and the Louisville Jug Bands, Vol. 3 (and also eMusic.)

Lightnin' Hopkins' "Automobile," built on a scaffold of Hopkins' harsh, ruminative guitar, was recorded in Houston and released as Gold Star 666 in November 1949; on The Very Best Of.

I'm not worried about my parking space

I just want to see my Savior face to face

You know prayer---is your driver's license

Faith---is your steering wheel

The Dixie Hummingbirds' 1957 "Christian's Automobile" is here given a brief intro by DJ Bob Dylan, in which Bonnie and Clyde and Henry Ford wind up giving testimony. The original is on Millennium Collection.

And the Divine Comedy's "Your Daddy's Car," which depicts an adolescence so charmed and stylish that it hurts to compare it to the real thing, is from the band's second album, Liberation, released in August 1993.

In Next Week Tomorrow

Superchunk, Precision Auto.

The Buzzcocks, Fast Cars.

The Sugarcubes, Motorcrash.

Jan and Dean, Dead Man's Curve.

Jimmy Carroll, Big Green Car.

Big Star, Big Black Car

Rush, Red Barchetta.

Time and space are at your beck and call; your freedom is complete.

Elon Jessup, The Motor Camping Book, 1921.

It is easy to hate motor culture, and you often have good reason to do so, but it might be well to remember that at the dawn of the past century, the car was seen as a liberating force, a means of achieving freedom.

As described in Michael Berger's The Devil Wagon, a history of the automobile's introduction to rural America, much of this belief was a reaction to what the railroads had become. While once the railroad had symbolized escape and potential, over time it had devolved into the industrial establishment, a great iron network run by monopolies and strike-breaking robber barons, and staffed by arrogant conductors; as Berger wrote, the railroads were seen as impersonal, overwhelming, filthy, overcrowded. Theodore Dreiser in 1916 wrote that "the railways have become huge clumsy affairs, little suited to the temperamental needs and moods of the average human being."

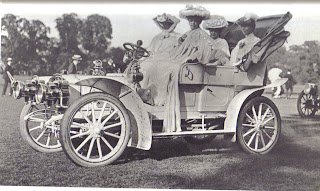

So when the car began growing in popularity in the early 1900s, it seemed to offer a return to spontaneity and intimacy--it was considered the true heir to the stagecoach, which, by the early 20th Century, had become idealized by a generation that had never had to ride in a creaky, slow, ass-numbing carriage.

Irish village helping stranded racer, 1908

If the train had created standardized time, the automobile offered freedom from railway schedules, a way to race away the clock. Even today it is a bit liberating to drive somewhere, rather than take a plane or train, as you don’t have to leave exactly on time, you don’t have to fumble for tickets, you don’t have to check baggage, wait in lines or doff your shoes so as to show you don't have a bomb in them.

"Glorious, stirring sight!" murmured Toad, never offering to move. "The poetry of motion! The real way to travel! The only way to travel! Here to-day--in next week tomorrow! Village skipped, towns and cities jumped--always somebody else's horizon! O bliss! O poop-poop! O my! O my!...

As if in a dream he found himself in the driver's seat; as if in a dream, he pulled the lever and swung the car round the yard and out through the archway; and, as if in a dream, all sense of right and wrong, all fear of obvious consequences, seemed temporarily suspended...He chanted as he flew, and the car responded with a sonorous drone; the miles were eaten up under him as he sped he knew not whither, fulfilling his instincts, living his hour, reckless of what might come to him...

Kenneth Grahame, The Wind in the Willows.

The automobile carried the future, especially for rural communities. No longer would people choose doctors, schools, churches, friends, occupations or lovers based entirely on their proximity. You could consider the car as an agent of centrifugal force, sending children away from parents, families from their homelands, sending urbanites fleeing from their tenements, rustics tumbling into cities.

For the first time in world history mass man became the master of a complicated piece of power machinery by which he could annihilate distance.

George Mowry, The Urban Nation, 1965-68.

Most of all, the car provided an individual human being, for the first time in history, with the power of a battalion. The car remains the most dangerous, the most powerful thing that most of us will ever control, a weapon that we use most days without realizing its catastrophic potential.

And you can go so fast! I know I've just written about my highway phobia, but in a more pleasant setting, I can't deny the pleasure of hitting the pedal, the speedometer arcing rightward, the greedy hum of the car as it takes on distance. It's no wonder the Futurists thought the car was something akin to a Greek god:

The words were scarcely out of my mouth when I spun my car around with the frenzy of a dog trying to bite its tail, and there, suddenly, were two cyclists coming towards me, shaking their fists, wobbling like two equally convincing but nevertheless contradictory arguments. Their stupid dilemma was blocking my way—-Damn! Ouch!...I stopped short and to my disgust rolled over into a ditch with my wheels in the air...

A crowd of fishermen with handlines and gouty naturalists were already swarming around the prodigy. With patient, loving care those people rigged a tall derrick and iron grapnels to fish out my car, like a big beached shark. Up it came from the ditch, slowly, leaving in the bottom, like scales, its heavy framework of good sense and its soft upholstery of comfort...

We affirm that the world's magnificence has been enriched by a new beauty; the beauty of speed. A racing car whose hood is adorned by great pipes, like serpents of explosive breath--a roaring car that seems to run on shrapnel--is more beautiful than the Victory of Samothrace.

We want to hymn the man at the wheel, who hurls the lance of his spirit across the Earth, along the circle of its orbit.

Marinetti, the First Futurist Manifesto, 1909.

Two speed manifestos:

Pro: Superchunk's "Precision Auto" is from 1993's On the Mouth.

Con: Sooner or later, you're going to listen to Ralph Nader. The Buzzcocks' "Fast Cars" is from 1978, originally on their first LP Another Music From a Different Kitchen; available on Operators Manual.

Opening her umbrella, the Baroness looked about her vaguely expecting to see the Queen.

The Queen always insisted while motoring on mending her punctures herself, and it was no uncommon sight to see her sitting with her crown on in the dust. Her reasons for doing so were complex; probably she found genuine amusement in making herself hot and piggy; but it is not unlikely that the more Philistine motive of wishing to edify her subjects was the real cause...

As [the Baroness] spoke there was a flash of diamonds, and the Queen whirled by in a cloud of dust. Like a shot Cameo she passed--all glimmering stones and pale mimosa hair, and wide dilated eyes.

Ronald Firbank, The Artificial Princess.

Two car crashes:

The Sugarcubes' "Motorcrash" is from 1988's Life's Too Good. The video features some nice Icelandic stunt driving.

And Jan & Dean's "Dead Man's Curve" had its origins in the sharp curve on Sunset Blvd. near the UCLA campus (according to Snopes, it's the hard right curve above Drake Stadium, marked with #78 on this map), and the song in particular was inspired by the wipeout that Mel Blanc (the voice of Bugs Bunny) had on the curve in 1961.

"Dead Man's Curve" was written by Jan Berry and Roger Christian, who owned, respectively, a Stingray and a Jaguar XKE, the cars that wind up racing in the song. Christian thought the race should end in a tie, but Berry was adamant that there needed to be a fiery crash, complete with sound effects (and even the sweep of a harp). Two years later, Berry, riding his Stingray near UCLA, plowed into a parked truck and was nearly killed.

Released in February 1964 as Liberty 55672 c/w "The New Girl in School"; on Greatest Hits.

You shall not kill.

The road shall be for you a means of communion between people and not of mortal harm.

Courtesy, uprightness and prudence will help you deal with unforeseen events.

Be charitable and help your neighbor in need, especially victims of accidents.

Cars shall not be for you an expression of power and domination, and an occasion of sin.

Some of the Vatican's 10 commandments for drivers, 2007.

Tour de France, 1909.

Two fine cars on the lot:

Jimmy Carroll's "Big Green Car" starts out with a typical car song dilemma--the singer sees his girl driving around with some guy in a nice new car, and despair ensues. However, there's a happy ending, if a bit weird, to this one (the singer didn't recognize his uncle?). Released, for some reason, under both the names Jimmy and Billy Carroll as Fascination 2000, c/w "That's All I Want" in December 1958; on All Mixed Up.

And "Big Black Car," in which Alex Chilton sits behind the windshield, hoping the world won't reach him, not truly caring if it does. From 1975's Third/Sister Lovers.

Finally, Rush's "Red Barchetta" ends this section with a bit of speculative fiction--in a future in which cars have been outlawed, our hero and his kindly uncle keep hope alive by hiding in a barn a mint Barchetta, which the kid takes out every week to taunt the authorities. After Alex Lifeson and Geddy Lee rock out, a chase ensues involving "a gleaming alloy air car," but don't fear--all's well that ends well. Based on Richard Foster's "A Nice Morning Drive," a short story published in Road and Track. (It also inspired the Lee Marvin movie The Last Chase.) On 1981's Moving Pictures. Likely the only song in the English language to use "alloy air car" in a lyric. Go Neil Peart!

The Horseless Carriage

The Model T Ford in its old age, 1926

Sleepy John Estes, Poor Man's Friend (T Model).

Rosco Gordon, T Model Boogie.

Then, like a cowboy shooting up a peaceful camp, a frantic devil would hurtle out of the distance, bellowing, exhaust racketing like a machine gun gone amuck--and at these horrid sounds the surreys and buggies would hug the curbstone, and the bicycles scatter to cover, cursing; while children rushed from the sidewalks to drag pet dogs from the street. The thing would roar by, leaving a long wake of turbulence; then the indignant street would quiet down for a few minutes--till another came.

'There are a great many more than there used to be,' Miss Fanny observed, in her lifeless voice, as the lull fell after one of these visitations. 'Eugene is right about that; there seem to be at least three or four times as many as there were last summer...but I think he may be mistaken about their going on increasing after this. I don't believe we'll see so many next summer as we do now.'

'Why?' asked Isabel.

'Because I've begun to agree with George about their being more a fad than anything else...Besides, people won't permit the automobiles to be used. Really, I think they'll make laws against them. You see how they spoil the bicycling and the driving; people just seem to hate them! They'll never stand it--never in the world! Of course, I'd be sorry to see such a thing happen to Eugene, but I shouldn't be really surprised to see a law passed forbidding the sale of automobiles, just the way there is with concealed weapons.'

Booth Tarkington, The Magnificent Ambersons.

Pitlochry, Scotland, 1906

The idea of a self-propelled automobile, like that of the steam-powered locomotive, had been around for centuries. As John B. Race described in his history of the automobile, Roger Bacon, for instance, wrote of "cars [that] can be made so that without animals they will move with unbelievable rapidity" and also predicted the airplane. Bacon, stuck at the height of the dark ages, evidently believed such cars had existed in the ancient world. Da Vinci, a few centuries later, brought up the same idea, predicting a vehicle roughly analogous to a modern tank.

In 1769, Nicholas Joseph Cugnot designed the first self-propelled car, a three-wheeled carriage powered by a steam engine. Yet throughout most of the 19th Century, few seemed to follow up on Cugnot's design. Part of it was due to the deliberate efforts of the railways, which pushed for high tolls on self-propelled vehicles, and, in 1865, achieved a major victory in Britain: what was known as the "red flag" law, which limited cars to a maximum of four miles an hour and required that each car needed to be preceded by a man on foot carrying a red flag. The law stayed on the books until 1896! (Several U.S. states had enacted similar laws, which were revoked around the same time.)

So while it is true the auto industry helped hobble the railroads and destroy the streetcars in the 20th Century, it frankly can be seen as a bit of payback.

At the dawn of the auto industry, circa 1895, there were a variety of competing auto types--electric cars, steam-powered cars, and those powered by the gasoline-fueled internal combustion engine, the latter best exemplified by vehicles designed by two German engineers, Karl Benz and Gottlieb Daimler. The names should give away which type of car won out.

Was there any one moment in which the Western world chose the gas-powered engine, which is responsible for everything from ExxonMobil to Saudi Arabia? In a park at the Porte Maillot, in Paris, is the first piece of public art to celebrate the car: a marble sculpture by Camille Lefèbvre (see above) that commemorates a French engineer named Emile Levassor who had won a Paris-to-Bordeaux auto race in 1895. The sculpture is a bit odd--it's an auto racing triumph done in the style of a Greco-Roman arch, and it depicts a speeding car trapped in marble. Still, as Robert Hughes wrote, since Levassor's victory helped cement the gasoline engine as the standard form of automobile propulsion, Lefèbvre's image should be far more known--copies of it should be erected in every oil port, its image emblazoned on the Riyal.

Another irony of the automobile's birth is that bicyclists, with whom car drivers unwillingly have shared the road for over a century, are in great part responsible for the car's growth. It was the bicycle industry that invented the pneumatic tire, for example; bicyclists were the first to call for street signs and paved roads, especially in the country, and many bike manufacturers wound up becoming automobile designers.

Motorist versus bicyclist, Toronto, 2006 (whole series here--warning: some frightening road-rage images.)

A toot from the bulb horn on the outskirts of each isolated Rocky Mount town ended every game of roulette and twenty-one as the inhabitants–-shepherds, traders, cowboys and starving Indians--crowded into the street to see the 'devil wagon'...on one occasion a redheaded woman on a white horse had sent Jackson and Crocker fifty-four miles out of their way, as it turned out, in order to pass her house so that her family could see an automobile. Some of the natives of the hinterland had never heard of a car. They thought the Winton was a small railroad engine that had somehow strayed off the track and was following the horse paths.

Ralph Hill, The Mad Doctor's Drive: Being an Account of the First Auto Trip Across the United States of America, or 63 Days On a Winton Motor Carriage.

For much of the 1890s and 1900s, the automobile was seen as a dangerous novelty of the urban rich. Yet slowly, car manufacturers began to cater to the middle class: Ransom Olds, with his Oldsmobile, and William Durant, a carriage manufacturer who controlled the Buick Motor Car Co.

Henry Ford and child

And of course, there was Henry Ford: mechanical genius, anti-Semite, visionary, hayseed. As Rae wrote, Ford, rather than intending to produce a car as cheaply as possible, instead designed a car that would appeal to the mass market, and then ground down manufacturing costs as low as he could. The result was the Model T, first unveiled in 1908, and which, for much of the first half of the past century, was the official American car, or the car that made Americans drivers.

Stephen Longstreet wrote of the Model T: Its illnesses were few, and the average citizen could attend to them with dime store parts. If the radiator leaked, sometimes throwing in a raw egg worked. There were anecdotal stories that an ailing Model T could fix itself--just leave it alone for a couple days, and when you started it again, it would be fine. The key to the car's success was that it was better built than its competitors' models, didn't need much time in the garage, and was long-lived. That formula remains a winner, except today it applies to Toyotas.

Around the town a horse is never seen

For every boob has bought a Ford machine

With gasoline.

"You'd Never Know That Old Home-Town of Mine," Walter Donaldson, 1915.

The Model T, also known as "Tin Lizzie" or "flivver" in slang (recall the lines in Gershwin's "Fascinatin' Rhythm": "The neighbors always want to know/why I'm always shaking, just like a flivver"), was manufactured until 1927, with few alterations. Henry Ford allegedly believed the standard Model T was all that a buyer would ever need, and for a while, he was right.

I believe now that motor cars are deeply religious. One may observe in the Monday morning papers the harvest of accidents of the day before. It must be very painful to a highly moral motor car to carry around a lot of joy riders who ought to be in church knowing better.

Louise Closser Hale, 1916.

Two Model T Ford odes:

Sleepy John Estes' "Poor Man's Friend (T Model)" was recorded in New York on 3 August 1937, with Estes on guitar, Charlie Pickett on guitar and Hammie Nixon on harmonica. Released as Decca 7442 c/w "Floating Bridge"; on this soon-to-be released collection and on Emusic.

And Rosco Gordon's "T Model Boogie" was recorded in Sun Studios on 4 December 1951, with Bobby Bland on backing vocals, Willies Sims and Weeks on saxophones and John Murry Daley on drums. It's a typically chaotic Gordon track, with Gordon losing his place mid-vocal, and wasn't released until 1977. On Yellow Sun Blues.

Road Trip

Hopper, Jo in Wyoming.

The Kinks, Drivin'.

Red Henderson, Automobile Ride Through Alabama.

Lindsey Buckingham, Holiday Road.

Nat "King" Cole Trio, Route 66.

We are seeing our country for the first time. It is not alone that a train window gives only a piece of whirling view; but the tracks go through the ragged outskirts of the town, past back doors and through the poorest land generally, while the roads become the best avenues of the cities and go past the front entrances of farms.

Emily Post, Motor to the Golden Gate.

In its early years, the automobile brought back, for a brief bright moment, the dream of the commons.

The history of the past 500 years is in part the growth of private property, with once-common land fenced, parceled and sold off. Yet the first car owners, who were typically urbanites, considered all of the land outside the cities theirs to use freely. So they would drive away from New York, or Chicago, or Miami, and simply park wherever they wanted, lounge on the grass, pick crops to eat, sleep overnight in a field--regardless of who owned it.

As you can imagine, this drove farmers and rural landowners mad, and for a while there was a guerrilla war waged against drivers: sometimes country people would throw broken glass and tacks across the roads, or string barbed wire across lanes they wanted to keep private. There were even stories of farmers trying to horsewhip motorists that sped past them. (Many more details in The Devil Wagon.)

This state of affairs began to change when rural people a) got cars of their own and b) realized they could make a great deal of money by bilking urban drivers. Thus the creation of ludicrous local speed limits (five miles an hour, say) which would generate a nice stream of revenue in the form of speeding tickets, thus the creation of the motor tourist industry. The old decaying barn on the hill--now a historical landmark! The gully where people used to dump their trash--now a scenic overlook!

By the late '20s the 'gypsy' auto campers had discovered what all bohemian early adapters eventually learn--clearing a path means that the masses follow you. So random, romantic squatting on farmland was replaced by pay-as-you-go auto camps, which in turn were replaced by cheap roadside motels. The rustic country stores that the first automobilers had loved gave way to roadside diners and shops, which in turn gave way to today's standardized interstate rest-stops, each one with a McDonald's, each one with a sad newsstand offering $11 coffee mugs and Sudoku books.

Some road trip songs:

I first heard the Kinks' "Drivin'" in the fall of 1990, when the lines "Seems like all the world is fighting/they're even talking of a war" seemed eerily prescient, given the buildup to what would be the First Gulf War. Now, seventeen years and many wars later, the lines seem to reflect a permanent condition. Anyhow, listen to Ray Davies: get in your car and take a drive somewhere. Take your mother if you want to. Recorded May 1969 and released the next month as Pye 17776 c/w "Mindless Child of Motherhood"; on Arthur.

Lee "Red" Henderson was a guitarist for Earl Johnson and His Dixie Clodhoppers, a string band based in Atlanta. In August 1928, Henderson recorded his only solo record, "Automobile Ride Through Alabama," with possible banjo accompaniment by Emmett Bankston. Part tall tale, part surrealist dream, it really can't be described--listen and be awed. Released as OKeh 45283; on The Roots of Rap.

Motor tourists discover California, 1931

Lindsey Buckingham's "Holiday Road" is, of course, the theme song of National Lampoon's Vacation, from 1983. It's a typical Buckingham production, filled with touches like the dog barking at the fadeout. Weirdly, while it's Buckingham's best-known solo song, "Holiday Road" has never been available on CD.

Finally, there's Bobby Troup's "Route 66," made immortal by Nat "King" Cole. This is a live recording of the Cole Trio from a Los Angeles radio show, from I believe early 1946 (the announcer indicates Cole hadn't yet released "Route 66" as a single, which he did in June '46). With Oscar Moore on guitar and Johnny Miller on bass. On The Magic of Nat King Cole.

Sex Drive

Ada Jones, Keep Away From the Fellow Who Owns an Automobile.

Robert Johnson, Terraplane Blues.

Jerry McCain, Courtin' In a Cadillac.

Memphis Minnie, Me and My Chauffeur Blues.

Duran Duran, The Chauffeur.

Rosetta Howard, Too Many Drivers.

Prince, Little Red Corvette.

The Embarrassment, Sex Drive.

Elastica, Car Song.

Out in an automobile, in with the girl you love,

Riding at ease on the wings of the breeze, like birds in the blue sky above,

Teach her to steer the machine, get both her hands on the wheel,

You kiss and you squeeze just as much as you please,

Out in an automobile.

"Out In an Automobile," 1905.

You know the story: with the arrival of the automobile, an unmarried couple could go somewhere out of town without any parental supervision. So it's no wonder that so many songs have been written over the past century about cars and sex, with the car serving as metaphor, means or simply prime location.

As the automobile began to grow in popularity, songwriters picked up on its racier connotations: hence the run of songs in the first two decades of the 20th Century, like "When He Wanted to Love Her (He'd Put Up the Cover)" or "In the Back Seat of The Old Henry Ford" or "Take Me Out for a Joy Ride."

One of Irving Berlin's first published songs was "Keep Away From the Fellow Who Owns an Automobile," sung here in a 1909 recording by Ada Jones. With grim lines like: "There's no chance to talk, squawk or balk/you must kiss him or get out and walk." Released as U.S. Everlasting Record 1594; available here.

I'm gonna get deep down in this connection - keep on tanglin' with your wires.

I'm gonna get deep down in this connection - hoo-well, keep on tanglin' with these wires.

And when I mash down on your little starter - then your spark plug will give me fire.

Robert Johnson's "Terraplane Blues" refers to the Hudson Terraplane, a popular all-purpose car of the '30s. "Terraplane" was Johnson's most popular song during his lifetime, and one whose vivid, filthy metaphors likely created whole musical genres--British electric blues, heavy metal. Recorded in San Antonio on 23 November 1936. On Complete Recordings.

Jerry McCain's "Courtin' in a Cadillac," in which McCain seems more excited about his car than his girl, is from 1955. Released as Excello 2068, on R&B Hits.

Two chauffeur fantasies:

Memphis Minnie's sublime "Me and My Chauffeur Blues," with Minnie and her husband, "Little Son Joe" Lawler, dueling on guitars, was recorded on 21 May 1941. On Me and My Chauffeur.

And Duran Duran's "The Chauffeur," from 1982, is best known for its video, the most notorious of a string of racy videos that made the band's reputation in the early '80s. "The Chauffeur" video, at my school, was a grubby pubescent legend: no one ever saw the video, so rumors of its contents abounded until it had evolved in the imagination into a lost chapter of The Story of O. Sadly, the actual video pales in comparison, though it does take itself quite seriously, seems to be warring between the desire to be a lingerie ad and an automobile ad, and, to give it credit, does get the jump on much of the "Continental" pseudo-erotica later attempted in Madonna videos and Calvin Klein Obsession ads. A feminist response.

As a song, "The Chauffeur" is one of the better Duran Duran tracks, with Nick Rhodes, providing the entire sonic picture from bird twitters to flutes, making the case that he could have replaced the whole band. On Rio.

move over baby, gimme the keys

Prince's "Little Red Corvette," the undisputed ruler of car sex songs, was released in October 1982 on the LP 1999, and as a single (the first smash of Prince's career) in early 1983. On The Hits.

Rosetta Howard's sick of it--you got too many drivers in your car, she tells her lover. "Too Many Drivers" was originally recorded by Smokey Hogg, and wound up in a number of different incarnations, including covers by Howard and Smiley Lewis, as well as being renamed "Little Car Blues" by Willie Love and His 3 Aces, "Little Side Car" by the Larks, and "Let Me Ride In Your Little Automobile" by Lowell Fulson. (Info: Marv Goldberg.) Howard's "Too Many Drivers," recorded in 1947 with the Big Three Trio, was one of her last recordings, released as Columbia 38029 c/w "Help Me Baby"; on Complete Recorded Works.

Mr. Brown drove out of town

Taking his wife

He took his wife

After so many metaphors, it's refreshing to feature a song as blunt and as awesome as the Embarrassment's "Sex Drive." The Embarrassment were a fine band based in Wichita, and who still remain undeservedly obscure though responsible for masterpieces like "Elizabeth Montgomery's Face," "Celebrity Art Party," "Lewis and Clark," "Woods of Love," and, of course, "Sex Drive," which was recorded in November 1979 and released a year later as a 7" single, Big Time 1, c/w "Patio Set". On the sadly out-of-print Heyday.

And finally, let's end this set with Elastica's "Car Song," whose car-hopping heroine would make Ada Jones faint. "Every shining bonnet/makes me think of my back on it." From 1995's Elastica.

Taxi!

Bernard Hermann, Taxi Driver.

The Mills Brothers, Cab Driver.

The Jewish day begins in the calm of evening, when it won't shock the system with its arrival. It was then, three stars visible in the Manhattan sky and a new day fallen, that Charles Morton Luger understood he was the bearer of a Jewish soul.

Ping! Like that it came. Like a knife against a glass...

He was not one to engage taxicab drivers in conversation, but such a thing as this he felt obligated to share...So he leaned forward in his seat, raised a fist, and knocked on the Plexiglas divider.

The driver looked into his rearview mirror.

"Jewish," Charles said. "Jewish, here in the back."

The driver reached up and slid the partition over so that it hit its groove loudly.

"Oddly, it seems that I'm Jewish. Jewish in your cab."

"No problem here. Meter ticks the same for all creeds." He pointed at the digital display.

Charles thought about it. A positive experience or, at least, benign. Yes, benign. What had he expected?

Nathan Englander, The Gilgul of Park Avenue.

Bernard Hermann's score for Martin Scorsese's Taxi Driver, Hermann's last, is on the original soundtrack; meanwhile, the Mills Brothers enlist their taxi driver in a bit of genial stalking. "Cab Driver" was one of their last singles, released in 1967. On Best Of.

The Age of Kings

Henry Ford unveils the V8 engine

Johnny Bond, Hot Rod Lincoln.

Jane Bond and the Undercover Men, Hot Rod Lincoln.

Sonny Boy Williamson, Pontiac Blues.

Jackie Brenston, Rocket 88.

Serge Gainsbourg, Ford Mustang.

The Beach Boys, 409.

Ronny and the Daytonas, G.T.O.

Peppermint Harris, Cadillac Funeral.

Chuck Berry, Dear Dad.

The White Stripes, The Big Three Killed My Baby.

After World War II, America (and a bit later on, Western Europe) entered the golden age of driving. Gasoline for a quarter per gallon, new federally-funded interstates opening Long Island and countless suburbs up to the masses, and with a host of new car models--larger, more extravagant, more powerful than ever. Ford, Chrysler and GM had devoured or destroyed all their competitors, and were utterly invincible. The era would last forever; it was over by the late '70s.

Here are a few remnants left from the high tide of car culture:

Johnny Bond, born Cyrus Whitfield Bond, was one of Gene Autry's regular sidekicks and had a sideline in country music, cutting nearly 80 singles for Columbia. So when Autry launched a new record label, Republic, in the late '50s, Autry signed Bond and asked him to re-record a song to which Autry owned the publishing rights, "Hot Rod Lincoln."

A nice bit of late rockabilly, "Hot Rod Lincoln" became Bond's only pop hit record, though the word-jammed lyric always proved troublesome for Bond, who never memorized it and mainly improvised whenever he played the song on stage. Recorded 25 May 1960 and released as Republic 2005; on The Golden Age of Rock & Roll Vol. 8.

Lincoln Futura, 1955

Jump ahead a few decades. Ethan James, though he had jammed with the Grateful Dead and was once a member of Blue Cheer, had embraced the California punk scene, producing the likes of Black Flag and the Minutemen. With the singer Lisa Mitchell, James recorded a goofy new wave record, Jane Bond and the Undercover Men, with the highlight being a girl's version of "Hot Rod Lincoln," all keyboard flourishes and snarky attitude. Released in 1982 as Ear Movie Records EM2S007 c/w "Come On Up" (which featured the Bangles on backing vocals.) Unavailable on CD.

Bechtle, '61 Pontiac

We gonna drive out on the highway, turn the bright lights off.

Oh, drivin' on the highway, cut the bright lights off.

We gonna turn the radio on and get music from up the north.

Sonny Boy Williamson's "Pontiac Blues," according to legend, refers to a new Pontiac owned by Lillian McMurry (who ran Trumpet Records) that she offered to Williamson if he agreed to take his wife, Mattie, with him on tour. (The Williamsons were evidently having marital problems, and Mattie and McMurry were friends.) Sonny Boy, again according to legend, turned McMurry down.

Released in May 1951 as Trumpet 144 c/w "Sonny Boy's Christmas Blues"; on Cool Cool Blues.

The Oldsmobile Rocket 88, which rolled out in 1949, was Olds' biggest seller in the early '50s--the Rocket had a smaller car frame but featured a souped-up V8 engine. Ike Turner and the Kings of Rhythm recorded the essential ode to it, under the name of Jackie Brenston and the Delta Cats, a track that often turns up as a prime candidate for "first rock & roll record," which it isn't. With Turner on piano, Raymond Hill (sax), Willie Kizart (g), Willie Sims (d). Recorded 5 March 1951 and released as Chess 1458 c/w "Come Back Where You Belong." On Legendary Sounds.

Un numéro

De Superman

Un écrou de chez

Paco Rabanne

Une photo

d'Marilyn

Un tube d'aspirine

On s'fait des langu's

En Ford Mustang..

Serge Gainsbourg's "Ford Mustang" is a counterpart to Godard's films of the same period, in which American culture, with its abundance of comic books, colas and, of course, cars, is both intoxicating and utterly destructive. Released on the 1968 EP Initials B.B., Philips 437431; on Initials SG.

The Beach Boys' "409" refers to the Chevrolet 409, so-called because the car had a ridiculous 409 cubic-inch V8 engine. According to the Muscle Car Club, who would know about such things, "the 409 was actually a response to Ford's new 390 cid engine, which was outperforming Chevy's on the dragstrip. Although it put out "only" 360 bhp compared to Ford's top 375 bhp, those extra 19 cid gave it respect on the street." Recorded 19 April 1962 and released as the b-side of "Surfin' Safari" in June. On Surfin' Safari.

And one of the finer Beach Boys knock-offs was Ronny and the Daytonas' "G.T.O", their debut single from late 1964. The Daytonas, a Nashville studio group led by John "Bucky" Wilkin, were likely singing about the 1964 Pontiac GTO, designed by Pontiac's John DeLorean and Russell Gee. "G.T.O" stood for Gran Turismo Omologato, a fairly meaningless term also used on Ferarris and Mitsubishis. Released as Mala 481; on GTO.

The decline and fall of the American auto industry needs no recounting. It was a fate possibly inevitable, given globalization and high oil prices, but much of what has occurred could have been avoided. It goes to show that arrogance and ignorance, which the car industry had in spades in the late '60s, are never favorable conditions for adapting to the future.

So Ford went from making the Model T, a car for working people whose selling point was that it didn't break down, to offering models like the Fairmont. A Ford Fairmont Futura was my first car, and it was such a lousy heap that I took to running red lights whenever I could, as the bastard would stall if you weren't flooring the gas. In the '80s, I once heard a friend of my father's say about a sickly car, "That's the problem with Fords--they never want to start." That about sums it up.

Even the mighty Cadillac, the crown prince of cars, is downsizing. In 2002, Cadillac discontinued the Eldorado, and the Seville two years later. A premature funeral for the Cadillac, from 1955, is officiated by Peppermint Harris. Released as Cash 1003; on R&B Hits of '55.

Chuck Berry's "Dear Dad," from 1965, is a long joke about an ailing Ford on its last set of tires, but sadly seems to predict the future of the U.S. auto industry. Recorded 15 December 1964 and released as Chess 1926; on Gold.

Finally there's Jack White's rant against the Big Three automakers and the blight of his hometown of Detroit, in which the auto martyrs, Preston Tucker and the El Dorado of the electric car, are invoked. "The Big Three Killed My Baby" was released in April 1999 c/w "Red Bowling Ball Ruth" as SFTRI-578, and included on the first White Stripes record.

Exit Ramps

Sibylle Baier, Driving.

Jimmy Nelson, T-99 Blues.

Gerry Mulligan Quartet, Freeway.

Howlin' Wolf, Driving This Highway.

For a couple years he'd been a used car salesman and so hyperaware of what that profession had come to mean that working hours were exquisite torture to him...

Yet at least he had believed in the cars. Maybe to excess: how could he not, seeing people poorer than him come in, Negro, Mexican, cracker, a parade seven days a week, bringing the most god-awful of trade-ins: motorized, metal extensions of themselves, of their families and what their whole lives must be like, out there so naked for anybody, a stranger like himself, to look at, frame cockeyed, rusty underneath, fender repainted in a shade just off enough to depress the value, if not Mucho himself, inside smelling hopelessly of children, supermarket booze, two, sometimes three generations of cigarette smokers, or only of dust--

and when the cars were swept out you had to look at the actual residue of these lives, and there was no way of telling what things had been truly refused (when so little he supposed came by that out of fear most of it had to be taken and kept) and what simply (perhaps tragically) had been lost...

Thomas Pynchon, The Crying of Lot 49.

Clyde Barrow and Ford

Hopefully, the heap of words that I've written about cars hasn't resulted in too hopeless a picture, as the automobile will be with us for many years to come. And the car has its moments. Such as the feeling of being out driving late at night, isolated yet attuned to the world. If our ultimate condition in this world is to be alone, as sometimes it seems, the car is the ideal vehicle for the task, serving as a suit of armor, a mobile home, an escape clause.

Four last car trips, each heading on a long road away:

Sibylle Baier's "Driving" was recorded sometime between 1970-73; on Colour Green, one of the finest reissues of the decade.

Jimmy Nelson, who hailed from the last generation of blues shouters, got his nickname, as well as the title of his essential song, from an old Texas highway running out of Fort Worth. Nelson's "T-99 Blues" is from 1951; on Blowing the Fuse.

Gerry Mulligan and Chet Baker's "Freeway" was recorded in Los Angeles on 15-16 October 1952. With Bob Whitlock on bass and Chico Hamilton on drums. On The Original Quartet.

Finally, we end with Howlin' Wolf, driving out on the highway alone. Recorded in West Memphis, Arkansas, on 12 February 1952, with Ike Turner on piano and Willie Steel on drums. On The Chronical.

Song suggestions, road stories: Skip Heller, Amy Granzin, J. Johnson, Rebecca DeCola and Mr. Bob Dylan. And a warm welcome to the world for future motorist Alice Griffin.

Essential reading: Michael Berger, The Devil Wagon in God's Country; Automobiles and Automobiling (Pierre Dumont, Ronald Barker); John B. Rae, The American Automobile; Tom Lewis, Divided Highways; Rutger Booy's Cars and Culture.