Ray and Bob, Air Travel.

Eddie Floyd, Big Bird.

Frank Sinatra, Come Fly With Me.

Away and away the aeroplane shot, till it was nothing but a bright spark; an aspiration; a concentration; a symbol (so it seemed to Mr. Bentley, vigorously rolling his strip of turf at Greenwich) of man's soul; of his determination, thought Mr. Bentley, sweeping round the cedar tree, to get outside his body, beyond his house, by means of thought, Einstein, speculation, mathematics, the Mendelian theory--away the aeroplane shot...

It was strange, it was still. Not a sound was to be heard above the traffic. Unguided it seemed; sped of its own free will. And now, curving up and up, straight up, like something mounting in ecstasy, in pure delight, out from behind poured white smoke looping, writing a T, an O, an F.

Virginia Woolf, Mrs. Dalloway.

The story of flying is, at its heart, a tragedy. Human beings had dreamed of flight for as long as they had dreamed, and at last, a century ago, the dream came true. For a sunlit day or so, the promise of flight made the human race drunk with possibilities, imagining itself liberated--from borders, prejudices, the past, from time itself. But soon enough wars, governments and commerce put paid to that, turning flight into what it is today: a combination of the horrific and the mundane. Or, as Orson Welles said in 1985, There are only two emotions in a plane: boredom and terror.

There is something unsettling about flying: even on the typical overcrowded plane of today, crammed in your seat in coach, a Ben Stiller movie flickering on a Post-It-Note-sized screen before you and a bland meal settling in your stomach, all it takes is a look out the window to realize you are engaged in something rather miraculous and a bit insane.

Flight’s only real predecessor is sailing (both are dependent on weather and wind, link far-flung countries, spread diseases) though flying seems far more outside the order of things, so that by engaging in it we go above our station, apes at the gates of Mount Olympus; flight also seems a mass delusion, a few hundred people sitting calmly in a metal tube soaring 40,000 feet above the earth, with all the power of gravity grasping us back down. I sometimes have wondered, while flying, whether the only reason the plane is aloft is that the passengers have simply willed it to do so, and that if enough of them stop believing, the plane will just fall out of the sky.

So songs about flying, while common enough, have been nowhere near as popular or as ubiquitous as train songs, or especially car songs, which seems to reflect both the fact that, up until thirty years ago, flying in an airplane was rarely done by the average person, and also that the idea of flight doesn’t convey much reassurance, happiness or nostalgia. Death and fear always have been part of flight: co-pilots, or at least passengers.

Princess Ludwig Lowenstein-Wertheim taking flying lessons, ca. 1909.

Ray Appleberry and Bobby Swayne, two journeymen R&B players, met in a Los Angeles studio doing session work. The two wrote "Air Travel," which seemed crafted to fill the gap between Sam Cooke and Rick Nelson hits, and pitched it to producer Fred Smith, the force behind most of the Olympics' singles. "Air Travel" was issued on the tiny label Ledo and got some attention by DJs in Detroit, Milwaukee and Boston, but because Ledo didn't have the muscle to push the song, the single wasn't even available for sale in cities where it got airplay, and unsurprisingly "Air Travel" flopped. Still, one of our battered airlines should use it as a jingle today.

Released in 1962 as Ledo 1151, and covered by Chris Farlowe a few years later in a version popular with the Mods. On Golden Age of Rock & Roll Vol. 8.

Eddie Floyd's "Big Bird" is his tribute to Otis Redding, who had died in a plane crash in late 1967. Floyd was inspired to write the song after his plane was delayed due to engine trouble at Heathrow, ultimately causing him to miss Redding's funeral. So the track's both a send-off to a heaven-bound Redding as well as Floyd venting at the forces keeping him on earth. The refrain "get on up big bird" comes back into my head sometimes, when I find myself in a plane straining to leave the runway and appearing as though it will shake apart before it does.

"As close as soul music has ever come to the deteriorated blues of heavy metal" (Dave Marsh). Recorded in Memphis in January 1968 and released as Stax 246 c/w "Holding On With Both Hands"; on Stax Profiles.

"Come Fly With Me" is Frank Sinatra at his most parodic--it's easier to picture Joe Piscopo or Phil Hartman delivering this than Sinatra himself. Given a garish Billy May arrangement and a Sammy Cahn lyric that ranges between over-clever and sloppy, Sinatra still manages to sell the song, with a vocal so enthralled with its own swagger that it saves the whole mess and makes it, in its own vulgar way, a standard.

Recorded 8 October 1957 in Los Angeles and released as, naturally, the lead-off track on Come Fly With Me.

Solitary Delights of Infinite Space

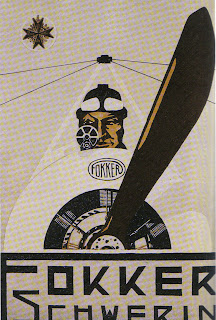

Rojan, lithograph, 1929: flight as modernist dream

Leo Ornstein, Suicide In an Airplane.

George Antheil, Airplane Sonata: As Fast As Possible.

The Beatles, Aerial Tour Instrumental (Flying).

John Byrd and Washboard Walter, The Heavenly Airplane.

Wilco, Airline to Heaven.

Ada Jones and Henry Burr, Come Josephine in My Flying Machine.

Helen Humes and Dexter Gordon, Airplane Blues.

And when the living creatures went, the wheels went by

them: and when the living creatures were lifted up

from the earth, the wheels were lifted up.

Ezekiel 1:19.

Of silver wings he took a shining pair,

Fringed with gold, unwearied, nimble, swift;

With these he parts the winds, the clouds, the air,

And over seas and earth himself doth lift,

Thus clad he cut the spheres and circles fair,

And the pure skies with sacred feathers clift...

Tasso, Jerusalem Delivered.

Robert Wohl, in his marvelous history A Passion for Wings, wrote of the coming of the airplane in the early years of the past century, arguing that airplanes, while emerging at the same time as the 20th Century’s other major forces—automobiles, radio, movies, telephones—seemed at the start to be of a different order. “The invention of the airplane was at first perceived by many as an aesthetic event,” he wrote. “Its invention inspired an extraordinary outpouring of feeling and gave rise to utopian hopes and gnawing fears.” While at first the airplane had little effect on how human beings lived, just the idea of someone up in the sky (besides God) was disconcerting and liberating.

Artists, naturally, claimed the airplane as one of their own. Novelists and poets like Gabriele D’Annunzio, Vasily Kamenksy (who flew a biplane until he was nearly killed at an airshow in Poland) and Guillaume Apollinaire celebrated pilots as the new men of the new century, artists whose technical feats would make the use of words or paint obsolete. Undaunted, painters like Delaunay and Kazimir Malevich tried to depict the power of flight, Malevich hoping that man and airplane eventually would fuse into one being and escape the earth. H.G. Wells thought it inevitable that airplanes would be used to annihilate cities, and in 1908 wrote of the aerial bombing of New York ("as airships sailed along they smashed up the city as a child will shatter its cities of brick and card...Lower New York was soon a furnace of crimson flames, from which there was no escape...")

Vladimir Lebedev and Kamensky with Blériot plane, 1911

And Kafka, watching airplanes fly at Brescia, Italy, in 1909, wrote afterward of a troubling notion that had come to him: that to the pilots in the air, the great crowd of people of which Kafka had been part must have melted into the plain, so that the crowd was no more human-seeming to the pilot than the guideposts or signaling masts. Though Kafka didn't pursue the idea further, its culmination is logical--to the abstracted eye of the pilot, cities are no more than squares and circles, and human beings barely ants.

Tullio Crali, 1939, bomber's-eye view of cities as empty geometry

Composers also tried to come to grips with the promise of flight, the first notable attempt being Ukraine-born Leo Ornstein’s 1918-1919 composition called “Suicide in an Airplane,” which features a rapid bass ostinato, allegedly to simulate the sound of plane engines; spiked with tone clusters, the brief composition conveys the sense of a plane descending, descending, but reaching no bottom. This performance is by Janice Weber and can be found on Piano Sonatas.

Ornstein's work inspired George Antheil (best known for his Ballet mécanique) to write his Second Sonata (“The Airplane”) in 1923. Here is the first movement, which Antheil noted should be played “as fast as possible.”

Linda Whitesitt: Airplane Sonata is the product of a series of spectacular dreams in which Antheil felt that he had "for once caught the true significance and atmosphere of these giant engines and things that move about us." Written in his hometown of Trenton before he left on his first European concert tour, it is the progenitor of his "time mechanisms”: "the future of the world lies in the vibration of its people. The environment of the machine has already become a spiritual thing.... For the great mass of us the war has killed illusion and sentimentality... Hence the birth of the Music-Mechanists."

Performed by Marthanne Verbit and found on Bad Boy of Music.

Rousseau, Les Pecheurs a la Ligne Avec Aeroplane.

Far more tranquil flying music: the Beatles' "Aerial Tour Instrumental,” the working title of a track ultimately released as "Flying" on the Magical Mystery Tour soundtrack EP. It was meant to accompany a sequence in which the tourists riding the Magical Mystery Tour bus look out the windows and, instead of the British countryside, see aerial shots of glaciers and mountains. The shtick was that each shot would be in a different color, a concept deflated when the Beatles failed to realize the film's intended audience (Boxing Day TV viewers) would almost entirely watch it on black-and-white television sets. Recorded 8 September 1967.

Delaunay, L'Hommage a Blériot.

Life expands in an aeroplane. The traveler is a mere slave in a train, and, should he manage to escape from this particular yoke, the car and the ship present him with only limited horizons. Air travel, on the other hand, makes it possible for him to enjoy the 'solitary delights of infinite space.' The earth speeds below him, with nothing hidden, yet full of surprises. Introduce yourself to your pilot. He is always a man of the world as well as a flying ace.

Early French airline advertisement, quoted in Oliver B. Allen's The Airline Builders.

Malevich, Suprematist Composition: Airplane Flying.

Given the utopian ideals associated with early flight, the idea of an airplane soaring so high it reaches heaven became a natural image in gospel music.

Guitarist John Byrd was born in Mississippi, likely in the 1890s. Bruce Eder’s bio in the All Music Guide to the Blues has it that Byrd moved to Louisville by the 1920s and mainly earned his living playing 12-string guitar in a band led by “Washboard” Walter Taylor. Byrd also cut some gospel tracks with Taylor under the name the Rev. George Jones, one of which, 1929's “The Heavenly Airplane,” features a backing vocal by Mae Glover (under the name “Sister Jones”).

"Heavenly Airplane" is an astonishing piece of music--reverent and bizarre (though I don't buy the AMG's smug assertion that this is a "comic" sermon), with Byrd delivering a sermon that's essentially an early rap, and blessed with some gracious singing by Glover. On Rare Country Blues.

I'm not sure if Woody Guthrie ever heard the song, but his "Airline to Heaven" seems like a natural sequel--the lyrics, written by Guthrie in 1939, were set to music 60 years later by Jay Bennett and Jeff Tweedy. On Mermaid Avenue Vol. II, from 2000.

The Vatican inaugurated its latest venture: a low-cost charter airline to ferry thousands of Catholic pilgrims from Italy to popular religious sites around the world...

Aboard Monday's flight, the airline's official slogan, "I'm Searching For Your Face, Lord," was imprinted on headrest covers throughout the 150-seat cabin. The carrier said that its flights would be staffed with a cabin crew "specialized in voyages of a sacred nature."

The Vatican may still find it tough to compete with established low-cost rivals, however. Ryanair, based in Dublin, already offers cheap flights to Santiago de Compostela from Rome. "Ryanair already performs miracles that even the pope's boss can't rival," Ryanair said in a statement.

New York Times, 28 August 2007.

From the spiritual to the secular: As with all forms of transportation, there are naturally some racy airplane songs, ranging from Prince's stewardess seduction on his "International Lover" (in which Prince is the stewardess, murmuring “We are now making our final approach to...Satisfaction") to the following two examples.

"Come Josephine in my Flying Machine" is considered an innocent novelty jaunt. This recording is from 1909, sung by Ada Jones, who apparently sang every bit of pop music written during the Taft Administration, and some guy named Henry Burr who is joined midway through by what sounds like a group of drunk firemen. Yet a closer listen will reveal "Come Josephine" to be the 1909 equivalent of something like "Darling Nikki"--it's a filthy, filthy song.

First he turns me over, then he starts to loop-de-loop

First he turns me over, then he starts to loop-de-loop

It takes a long long time

till his wings begin to droop

Helen Humes' "Airplane Blues" is a wonderful track that Humes recorded with Dexter Gordon, a fusion of the emerging R&B and waning swing styles.

With Vernon Smith (tp), Ernie Freeman (p) Red Callender (b), J.C. Heard (d). Recorded in Los Angeles on 20 November 1950 and released c/w “Helen’s Advice” as Discovery 535. On Blues N Boogie.

Learning to Fly

My daily life is changed. I see everything from another angle. A draught, a journey, an engine starting, a bee buzzing against a pane...all remind me of my aviation.

Life is finer and simpler. My will is freer. I appreciate everything more, sunlight and shade, work and my friends. The sky is vaster...

When I am walking, motoring or in the train I look at the country only from one point of view--is it good for landing or not.

H. Mignet, The Flying Flea.

The dream of human flight was theorized and disastrously attempted for nearly 3,000 years.

The list of failed aeronauts and mad inventors is near-endless, ranging from Archytas of Taranto, a geometer, ca. 400 BC, who created a flying wooden pigeon, to Johann Müller, who allegedly built an "iron fly" that he sent out to welcome the Emperor Charles V upon a victory in battle. Or Lauretus Laurus, who theorized that, since eggshells without their yolks were naturally very light, and given that dew rose from the grass in the morning due to the sun's influence, thus empty eggshells filled with dew and exposed to the sun's rays would naturally float in the air. There is sadly no record as to his experiments' success.

There were the likes of John Wilkins, Lord Bishop of Chester, who wrote in 1648 there were four precise ways man could achieve flight--via spirits or angels, with the help of fowls, with wings fastened to the body, and by a flying chariot; Edward Somerset, the Marquis of Worcester, and author of a volume called "A Century of Inventions," the 77th invention being, he claimed, flight: a theory he had "tried with a little Boy of ten years old in a Barn, from one end to the other, on a Haymow"; the Friar Bartholomeo Lourenco de Gusmão, who built a "Passarola," essentially a large kite in the form of a bird; or the Marquis de Bacqueville, who attached large paddle-shaped wings to his wrists and ankles and tried to flap across the Seine, instead landing on a washerwoman's barge and breaking both legs.

By the late 18th Century, hot-air balloons had become a viable concept, but another century would pass before heavier-than-air flight, long the field of crackpots and casualties, became a reality.

This was the doing of two young bicycle manufacturers from Dayton, Ohio, the sons of a bishop in the Church of the United Brethren in Christ. The elder brother was a depressive who, after being struck in the face with a hockey stick, didn't leave his parents' house for three years; the younger, more outgoing, devoted his whole life to supporting his brother's bizarre schemes. They were inseparable and "both seemed to have understood, implicitly, that the only marriage they would have would be with one another" (Robert Wohl). They were, of course, Wilbur and Orville Wright.

Heavier-than-air flight had been theorized, attempted, bungled and written off long before the Wrights took it up. Yet the Wrights began their experiments in 1899 and flew four years later. In retrospect, their success seems quite simple--they began trying to fly at a moment when much of the theoretical groundwork had been laid, had familiarized themselves with the best ideas, and just went to work. No governments, no patrons, just two men spending months living in a tent on a Kitty Hawk beach, building gliders with motors, flying them off sand dunes.

First flight, December 1903

The Wrights soon realized that the core problem of flight was not in getting off the ground, but keeping in the air and learning to maintain balance in the mix of winds. (Being bicyclists was a help). By 1900, the Wrights had determined a glider could be controlled in flight if its wings were "warped": that is, if the outer portion of the trailing edge of the wings was twisted in inverse directions (Wohl). This concept, which makes for smooth and easy turns in mid-air, is used in every airplane in existence today. By 1903, the Wrights had hit upon using a propeller as a sort of supplemental airplane wing moving in a spiral, and had invented their own 12-horsepower engine. They first flew in December 1903, and spent the next few years convincing people they actually could fly.

French caricature of Wilbur Wright, Puritan aviator

The U.S. government had no interest in the Wright's plane, so the Wrights began looking overseas for customers, negotiating with the British, French and German governments. The French, who were supporting a number of home-grown aviation efforts, didn't believe the Wrights could fly, so Wilbur went over in 1908, successfully flew at Le Mans, and became a sensation. The Wrights contracted with a French manufacturer to sell Wright aircrafts, and Wright himself built the first models, serving as a example of American Puritan wizardry--working alone at an automobile factory, cooking his own meals, mending his own clothes. A French journalist wrote of Wright that "he made me think of those monks of Asia Minor who lived perched on the tops of inaccessible mountain peaks. The soul of Wilbur Wright is just as high and faraway." And so the mythology began.

Gods and Goddesses

The Hot Shots, Snoopy Versus the Red Baron.

Benny Goodman Orchestra with Charlie Christian, Solo Flight.

Rev. Leora Ross, God's Mercy to Col. Lindbergh.

Al Stewart, Lindy Comes to Town.

Vernon Dalhart, Plucky Lindy's Lucky Day.

Woody Guthrie, Lindbergh.

Neko Case, Lady Pilot.

The Country Gentlemen, Amelia Earhart's Last Flight.

The popular image of the aviator hero emerged out of a confluence of personalities and archetypes--the taciturn, economic and aloof Wilbur Wright; the suave Louis Blériot; the elite warriors in the novels of Émile Driant; the soaring supermen of D'Annunzio's ur-fascist fantasies.

Most of all, it was the First World War that cemented the idea of the aviator as a daring lone knight, someone warring and striving at a level high above the masses. This case, literally: while the average soldier spent years stuck in the same few miles of ground, sleeping and dying in trenches, he watched airplanes soar and duel overhead. Soon all the warring nations, in particular France and Germany, realized the tremendous propaganda value of their "flying aces."

The French had Roland Garros, who helped devise a method by which a machine gun could be synchronized with propeller blades (thus making aerial combat much easier) and Georges Guynemer, while the Germans burned through a string of aces--Oswald Boelcke, Max Immelmann, and the ace of aces, Manfred von Richthofen, the Red Baron. None of them survived the war.

War-weary Snoopy (click to enlarge)

"Snoopy Versus the Red Baron" is a remnant from an odd fad that may well utterly baffle future generations. In the 1960s, Charles Schultz began having Snoopy sit on his doghouse roof and imagine fighting the Red Baron, and the surreal fantasy struck a chord with a generation of readers, at the height of the U.S. war in Vietnam.

In 1966, the Royal Guardsmen had a novelty hit with "Snoopy Versus the Red Baron," which, as novelties go, is pretty violent, with its depiction of slaughtered pilots littering the German countryside. This is a ska version of the song from 1973, by a band called The Hot Shots about whom I know utterly nothing, except that I'm guessing they were a studio group. On Trojan UK Hits.

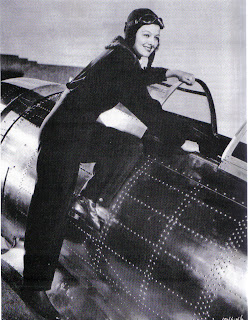

Harriet Quimby

The exploits of the flying aces fed the dreams of a slightly younger generation, those born too late for glory, like William Faulkner, who was still taking flying lessons when the war ended, or Charles Lindbergh, from Michigan, who left college in 1922 to buy his own airplane and become a "barnstormer."

The '20s were an evangelical period for aviators, all trying to break new records for duration or speed (which they hoped would increase public interest in flying and, more importantly, expand the number of investors willing to back aviation projects). By 1927, the key race was to see who would be first to fly solo across the Atlantic. The odds were on the French aviator Charles Nungesser (who tried and crashed somewhere at sea) and the Navy commander Richard Byrd, who had flown to the North Pole. But, in a story that seems crafted by Hollywood, Lindbergh came out of nowhere, with only modest financial backing, and flew from New York to Paris.

"Solo Flight," in which the great guitarist Charlie Christian soars above Benny Goodman's Orchestra, was recorded on 4 March 1941. On Essential BG.

It is hard to imagine, even in a media- and celebrity-saturated age such as ours, just how famous Lindbergh became after his flight, or, more to the point, how loved he was, by Americans, of all races, classes and ages. (Not just Americans were enthralled--Kurt Weill, Paul Hindemith and Bertolt Brecht in 1929 wrote "Der Lindberghflug" (The Lindbergh Flight)). People regarded Lindbergh as a mirror for their own aspirations, as the embodiment of the country at its finest, as an excuse to party. "Even the first walk on the moon doesn't come close," wrote Elinor Smith Sullivan, about the Lindbergh mania. "The twenties was such an innocent time, and people were still so religious–-I think they felt like this man was sent by God to do this."

As an example, here is the Rev. Leora Ross, a female African-American preacher, who seems to regard Lindbergh's flight as something to be commemorated in a third Testament. I know nothing about Ross besides the fact she recorded a few sides for OKeh in the '20s--the story of a female reverend who also was a recording artist seems fascinating enough that someone ought to do further research. Recorded in Chicago on 14 December 1927, and Ross is backed by the Church of the Living God Jubilee Singers; on Preachers and Congregations.

Or take Al Stewart's re-imagining of Lindbergh mania in "When Lindy Comes to Town," off his 1995 Between the Wars.

Anne Morrow Lindbergh

Lindbergh soon married Anne Morrow, the daughter of Dwight Morrow, Calvin Coolidge's best friend (a courtship recounted in Vernon Dalhart's "Plucky Lindy's Lucky Day"--it had gotten to the point where Lindbergh's every act was being depicted in song, as though he was a medieval king). They began to fly in tandem, suggesting a 20th Century brand of nobility--brave, untouchable, yet modest and meritocratic.

As from a Towre he thought to scale the Sky,

He brake his necke, because he soared too high.

Geoffrey of Monmouth, Historia Regum Brittaniae.

And then it went to smash. The horrific kidnapping and murder of their infant son in 1932 (and the media circus trial of the alleged kidnappers over the next two years) caused the Lindberghs to flee the United States and live in seclusion in the U.K. And it was there, a few hours' flight from Nazi Germany, that Lindbergh began to be courted by the likes of Hermann Göring.

Lindbergh was a Midwestern American with all the prejudices of his age, was fairly naive and quite stubborn in his opinions, and, most of all, was a zealot for flying. So Germany's shining new Luftwaffe, and Nazi propaganda about the aviator being a natural leader, a higher order of being, certainly got his imagination.

After all, the fascists in Italy and, later, Germany, regarded the airplane as their natural property. Mussolini, for example, was obsessed with flying, considering it to be a means of moving "the torpid soul of the masses." And after Hitler came to power, Göring, who had served in the Red Baron's squadron during the last year of the First World War, was charged with building a new air force to dominate all others. "I collect planes like others collect postage stamps," he told a subordinate.

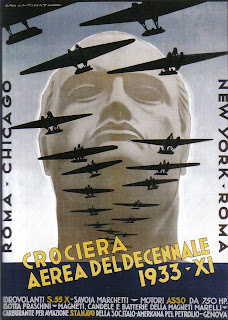

1933: Mussolini as god of flight

The severity and the purity of the idealized airman became part of the fascist mythology. Take the sermon given to air force recruits by a fascist Vice Marshall in Rex Warner's novel The Aerodrome, from 1941:

Your business as members of the Air Force is first and foremost to obtain freedom for the recognition of necessity; and necessity is no soft and feeble thing. It is not your business to attach yourself in any permanent sense to a woman. The thing is neither possible nor desirable…

Remember that we expect from you conduct of a quite different order from that of the mass of mankind. Your purpose—to escape the bondage of time, to obtain mastery over yourselves, and thus over your environment –must never waver. You will discover, if you do not know already, from the courses which have been arranged for you, the necessity for what we in this force are in the process of becoming, a new and more adequate race of men…

Science will show you that in our species the period of physical evolution is over. There remains the evolution, or rather the transformation, of consciousness and will, the escape from time, the mastery of the self, a task which has in fact been attempted with some success by individuals at various periods, but which is now to be attempted by us all...

They say America First, but they mean America Next

So Lindbergh went back to the U.S. and became the face of the isolationist movement, warning against war with Germany. He embodied the fears of many Americans wary about another catastrophic war, but the more he spoke, the more the mask came off:

Instead of agitating for war, the Jewish groups in this country should be opposing it in every possible way for they will be among the first to feel its consequences. Tolerance is a virtue that depends upon peace and strength. History shows that it cannot survive war and devastation. A few far-sighted Jewish people realize this and stand opposed to intervention. But the majority still do not.

Their greatest danger to this country lies in their large ownership and influence in our motion pictures, our press, our radio and our government.

Charles Lindbergh, "Who Are the War Agitators?" speech, Des Moines, 11 September 1941.

[Aviation] is a tool specially shaped for Western hands, a scientific art which others only copy in a mediocre fashion, another barrier between the teeming millions of Asia and the Grecian inheritance of Europe--one of those priceless possessions which permit the White race to live at all in a pressing sea of Yellow, Black and Brown.

Charles Lindbergh, "Aviation, Geography and Race," Reader's Digest, November 1939.

Vichy France propaganda poster: Satanic FDR gloats over bombed city

Woody Guthrie's "Lindbergh", which addresses not the hero aviator but the repellent public figure he had become, was recorded in 1944, and refers to the threat of Lindbergh winning the Republican nomination for president in 1940 (the nightmare scenario of Philip Roth's The Plot Against America). On Asch Recordings Vol. 1.

After the war (during which Lindbergh tried to enlist and was rejected, though he did work as a consultant in the Pacific War), the Lindberghs tried to restore their reputations, as an author in Anne's case, while Charles was an airline consultant for years (during which he apparently fathered a number of Germans.) The Lindberghs were forgiven by some, are forgotten by more each year. Lindbergh died in 1974, but he had been declared mortal long before.

Clark Gable in Test Pilot.

If Lindbergh showed the limits of the aviator dream, having turned out to be just as flawed, if not more so, than those stuck on earth, Amelia Earhart was flight incarnate--disappearing in the air into legend, forever young and beautiful.

The first woman to fly solo across the Atlantic, Earhart, while attempting a round-the-world flight, was lost along with her navigator Fred Noonan somewhere near the Nukumanu Islands in the South Pacific. Neither the plane nor its passengers were ever found, thus setting in motion a host of wild theories--that the Japanese had shot down Earhart, who had been spying on them at the behest of FDR; that she had survived the flight, but changed her name and went to live in obscurity in New Jersey.

Neko Case's "Lady Pilot" is off her fine 2002 record Blacklisted.

Myrna Loy, from "Wings in the Dark."

The Country Gentlemen's ode to Earhart is on their 1968 album Traveler and Other Favorites. On The Early Rebel Recordings and iTunes.

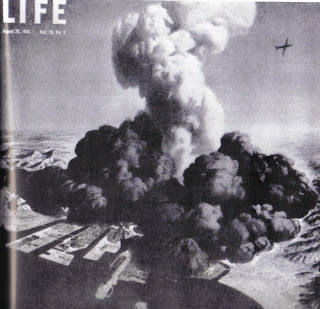

Death from Above

The Freshmen, Bombing Run.

The Clash, Spanish Bombs.

Sir Arthur Harris, Voice of Bomber Command.

Stephen Spender, Thoughts During an Air Raid.

Camper Van Beethoven, Sweethearts.

Cohen spoke for the first time. “If we’re going to talk about bombing, let’s be as scientific as possible. The target map of Berlin is just a map of Berlin with the aiming point right in the city centre. We are fooling only ourselves if we pretend we’re bombing anything other than city centres.”

“What’s wrong with that?” said Flight Lieutenant Sweet.

“Simply that there are no factories in city centres,” said Lambert. “The centre of most German towns contains old buildings: lots of timber construction, narrow streets and alleys inaccessible to fire engines. Around that is the dormitory ring: middle class brick apartments mostly. Only the third portion, the outer ring, is factories and workers’ housing.”

Cohen said, “One has only to look at our air photos to know what we do to a town.”

“That’s war,” said Battersby tentatively. “My brother said there’s no difference between bankrupting a foreign factory in peacetime and bombing in wartime. Capitalism is competition, and the ultimate form of that is war.”

Lambert smiled and rephrased the notion. “War is a continuation of capitalism by other means, eh Batters?”

Len Deighton, Bomber.

Ernst, Murdering Airplane.

It used to be that you could see death coming from a ways away--the wave towering over the ship, the rockslide, the hordes of barbarians streaming through the breached wall. But with the airplane, death could strike, for the first time, from above, from out of the clear sky with little warning.

Most of us have lived our entire lives vaguely aware that, for whatever reason or for no reason at all, a plane could appear from out of nowhere, drop a bomb and kill us. Such a thought has done wonders for the psychic health of mankind.

("Bombing Run" is by the Freshmen, an Irish rock & roll band who began performing before the Beatles first recorded and kept going until the last days of punk. The mainstays in an-ever changing lineup were keyboardist/saxophonist Billy Brown and trombonist Sean Mahon. "Bombing Run" was the b-side of one of the band's last singles, 1979's "You Never Heard Anything Like It", Release 975.)

During the First World War pilots had attempted to drop bombs on enemy forces and supplies, but their targeting skills were so spotty that generals eventually gave up, considering bombing a waste of resources. But the idea of "strategic bombing" was left on the table, and in the twenty years between the wars, the technology to do it properly came up to speed.

So by the 1930s, the idea of a city, a purely civilian target, being annihilated from the air was no longer in the realm of fiction. Civilian bombing began as rumors, from wars only known in dispatches or newsreels--the Japanese bombing of Shanghai in 1932, or the Italians' attacks on Ethiopia three years later. Then came Spain.

Guernica, 1937, after bombing

During the Spanish Civil War, which became the laboratory for the fascists and Communists for their own future wars, Franco had ordered his German air force "volunteers," led by Hugo von Sperrle and Wolfram von Richthofen (the Red Baron's cousin), to pacify the Basque provinces. So the Nationalist bombers first hit Durango, killing hundreds of civilians, and then, on 26 April, they leveled Guernica, dropping 100,000 pounds of bombs, with airplanes strafing the survivors. Richthofen considered the effects of the one-kilo I.G. Farben incendiary bombs to have been "a complete technical success." (Wohl.)

"Spanish Bombs" is on London Calling.

Aftermath of bombing raid in Things to Come, 1936.

London, view from St. Paul's after night bombing, 1940

So when WWII began in 1939, so did the widespread bombing of cities. The Nazis pummeled London for years, and by 1942 the UK Air Ministry had removed all constraints on its air raids, giving the go-ahead for massive strikes on German civilians.

Sir Arthur Harris, head of Bomber Command, was a true believer in the power of civilian bombings, ordering the complete destruction of cities like Lubeck, Rostock, Cologne. "Voice of Bomber Command" is a compilation of radio broadcasts from the 1942-43 period, featuring some of Harris' more apocalyptic pronouncements. Yet by the war's end, it was unclear whether the civilian bombings had done much to reduce the Nazi war effort.

Yet supposing that a bomb should dive

Its nose right through this bed, with me upon it?

The thought is obscene. Still, there are many

To whom my death would only be a name,

One figure in a column...

Stephen Spender’s “Thoughts During an Air Raid," from 1939: the quiet voice of the civilian, lying in bed, wondering which of the planes droning towards his city contains the makings of his death.

LIFE artist's rendering of Enola Gay winging away from Hiroshima, 1945

Angels' wings are icing over

McDonnell-Douglas olive drab

They bear the names of our sweethearts

And the captain smiles as we crash...

Camper Van Beethoven's "Sweethearts," a look inside the mind of Ronald Reagan at the end of his reign, is also a ode to bombers, emblazoned with the names of girlfriends, actresses and pinups, opening their arms (and dropping bombs, which, like flowers, "bloom where you have placed them" ) over Hiroshima, China, Vietnam, Cambodia, and on into the current war. From 1989's Key Lime Pie, their masterpiece.

In Case of an Emergency

Brian Eno, Burning Airlines Give You So Much More.

Stephanie Mills, Pilot Error.

The Rolling Stones, Flight 505.

Blondie, Flight 45 (Bermuda Triangle Blues).

Gene Clark and Carla Olson, Deportee (Plane Crash at Los Gatos).

Every time we hit an air pocket and the plane dropped about five hundred feet (leaving my stomach in my mouth) I vowed to give up sex, bacon, and air travel if I ever made it back to terra firma in one piece.

Erica Jong, Fear of Flying.

Why is an airplane crash so unnerving? After all, car crashes are a routine, horrific experience, and trains and ships have their fair share of casualties. Yet the idea of suddenly plummeting down to earth, the screaming of failing engines, the oxygen masks falling from the ceiling, is the stuff of nightmares. The use of airplanes as flying bombs in the 9/11 attacks added yet another layer to the horror.

A few musical considerations of plane crashes:

Brian Eno originally wrote a song called "Turkish Airlines Give You So Much More," inspired by the crash of a Turkish Airlines DC-10 outside Paris. As Eno said in an interview years later, it's not really a crash song as much as a musing on man's addiction to novelty and the false promise of modernity the airplane offers:

It is the feeling I remember of that, that someone from our world, from the West, shooting across China in a plane. And meanwhile, down below, in a rice paddy, is some old guy with long moustaches, thinking about the things that humans have been thinking about for the last 5,000 years. And, I think that was what that song was about, the difference between flying at speed through the modern world, which is the same world that this man inhabits.

On 1974's Taking Tiger Mountain By Strategy.

Stephanie Mills' "Pilot Error", from 1983, turns the idea of a jet crash into a metaphor for a fumbling lover. Adams wants her man to land safely, but she’s getting frustrated with how whack he’s been flying. Don't miss the video, from the era of "let's film anything", so there's chimpanzees, dancing runway signallers, etc.; on Gold.

The Rolling Stones' "Flight 505": the singer, formerly content in his middle-class life, suddenly feels the death urge, so he books a flight, orders a drink, watches his plane drop in the sea. Opens with 12 bars of honky-tonk piano bliss by Ian Stewart. Recorded 6-9 March 1966 in Hollywood; on Aftermath.

Blondie's "Flight 45," lost over the Bermuda Triangle, is on 1977's Plastic Letters.

Woody Guthrie wrote "Deportee" as a poem after reading about a plane crash in Los Gatos canyon, near Fresno, California, in January 1948. Guthrie was struck by the fact that newspapers and radio didn't mention any passenger names, as the passengers were all illegal Mexican aliens being deported (and whose bodies were put in a mass grave), instead simply calling the 28 dead "deportees" while taking pains to name the four native-born crew members also killed.

A decade or so later, a schoolteacher named Martin Hoffman set Guthrie's words to music, and the track was soon picked up by Pete Seeger and, later, the Byrds. Gene Clark, an original member of the Byrds, recorded the version here with Carla Olson--it was one of Clark's last recordings before his death in 1991. On 1987's So Rebellious A Lover.

High Society

Alphaville, The Jet Set.

The Specials, International Jet Set.

Penguin Cafe Orchestra, Chartered Flight.

Recollections of the 'golden age' of flight in the '60s: no IDs required, lots of smoking, leering at stewardesses, airports that could double as fashion runways.

Three luxury flights:

The German synth-pop band Alphaville's "Jet Set" was one of their first singles, from 1984. On First Harvest.

The Specials' "International Jet Set," luxury at its queasiest, is on 1980's More Specials.

And the Penguin Cafe Orchestra's "Chartered Flight" is from their first record, 1976's wonderful Music From the Penguin Cafe.

Stuck in the Air

Paul Revere and the Raiders, The Great Airplane Strike.

The Replacements, Waitress in the Sky.

Afroman, Airport.

Sara Nelson, a United Airlines flight attendant...saw family members whose flight was canceled "claw" a customer-service agent until her arms bled when the agent couldn't get them onto another flight.

In July, a doctor who missed his Northwest flight in Seattle allegedly called 911 three times to say there was a bomb on board, hoping the plane would return so he could make the flight, according to a FBI affidavit filed in U.S. District Court in Seattle...

In August, a passenger on a flight to Dallas from Buenos Aires drank two-thirds of a bottle of duty-free liquor, got into a confrontation with several passengers, then urinated in the cabin before passing out in his seat. Police were called to meet the plane.

"Fliers Behave Badly Again as 9/11 Era Fades," Wall Street Journal, 12 September 2007.

So having begun life as the embodiment of the future, of the New Man, of the fascist and democratic dreams, as the antechamber to escaping the earth, and as a way to obliterate distance and remove yourself from the masses, flying, in 2007, is bureaucratic, over-crowded, inept, unpleasant and potentially murderous.

You could blame deregulation (as airline CEOs have), or the destruction of the air traffic controllers union, or the decline of the railways (leaving airplanes as the only means for long-distance travel), or botched anti-terrorism efforts, or Orbitz. The end result is what you have today--flying has never been cheaper, and likely has never been more unbearable.

Some airline gripes:

Paul Revere and the Raiders' "Great Airplane Strike" from 1966, finds the singer unable to get off the ground--he tries to book a space on a plane wing to no avail, winds up losing his mind in an airline bathroom (insert Sen. Larry Craig joke here). On Greatest Hits.

"Don't treat me special or don't kiss my ass/Treat me like the way they treat em' up in first class." The Replacements' "Waitress in the Sky" is off 1985's Tim.

The air is annoyingly potted with a multitude of minor vertical disturbances which sicken the passengers and keep us captives of our seat belts. We sweat in the cockpit, though much of the time we fly with the side windows open. The airplanes smell of hot oil and simmering aluminum, disinfectant, feces, leather, and puke ... the stewardesses, short-tempered and reeking of vomit, come forward as often as they can for what is a breath of comparatively fresh air.

Ernest K. Gann, describing airline flying in the 1930s.

And Afroman's "Airport", from 2004, depicts a sadly typical air travel experience--anger, frustration, prejudices breeding new prejudices, with an overall feeling that everyone, from crew to passenger to ticket agents, is trapped in a hateful world of someone else's devising. On Afroholic.

Night Flight

Liz Phair, Stratford-On-Guy.

Joni Mitchell, This Flight Tonight.

Lionel Hampton, Flying Home.

There is not much to say about most airplane journeys. Anything remarkable must be disastrous, so you define a good flight by negatives: you didn't get hijacked, you didn't crash, you didn't throw up, you weren't late, you weren't nauseated by the food. So you're grateful.

Paul Theroux, The Old Patagonian Express.

Three last nighttime flights--flight as means of philosophy (Liz Phair's "Stratford-on-Guy," from 1993's Exile In Guyville), as an unwanted escape (Joni Mitchell's "This Flight Tonight," from Blue) and as an agent of pure joy (Lionel Hampton's 1942 recording of "Flying Home," on Over There.)

This post owes a ridiculous amount to Robert Wohl's A Passion for Wings: Aviation and the Western Imagination 1908-1918 and The Spectacle of Flight: 1920-1950. Highly recommended.

Other sources: Alexander Magoun, History of Aircraft; Lee Kennett, The First Air War; Wings: Anthology of Flight (ed. HG Bryden).

Endgame: "7 Means" is almost over, thank heavens. One more very minor interlude, and a final entry which will be more epilogue than anything else. Thanks for persevering with this never-ending series...