1957

Al Cohn and Zoot Sims, Two Funky People.

Brenda Lee, Dynamite.

The Cues, Why.

Tommy Blake, Lordy Hoody.

Bola Sete, Aquarela do Brasil.

Al Simmons with Slim Green and the Cats From Fresno, Old Folks Boogie.

Magic Sam, All Your Love.

Johnnie and Jack, That's Why I'm Leavin'.

Henri Pousseur, Scambi.

Jenks "Tex" Carman, Wolf Creek.

Jean Shepard, The Other Woman.

The "5" Royales, Say It.

Jackie Lee Cochran, Mama Don't You Think I Know.

Ellis Larkins, I Don't Stand a Ghost of a Chance With You.

I'm praying that you'll buy ON THE ROAD and make a movie of it...Don't worry about the structure, I know to compress and re-arrange the plot a bit to give a perfectly acceptable movie-type structure: making it into one all-inclusive trip instead of the several voyages coast-to-coast in the book, one vast round trip from New York to Denver to Frisco to Mexico to New Orleans to New York again. I visualize the beautiful shots could be made with the camera on the front seat of the car showing the road (day and night) unwinding into the windshield, as Sal and Dean yak. I wanted you to play the part because Dean (as you know) is no dopey hotrodder but a real intelligent (in fact Jesuit) Irishman. You play Dean and I'll play Sal (Warner Bros. mentioned I play Sal) and I'll show you how Dean acts in real life...

All I want out of this is to able to establish myself and my Mother a trust fund for life, so I can really go around roaming around the world...to write what comes out of my head and free to feed my buddies when they're hungry...what I want to do is re-do the theater and the cinema in America, give it a spontaneous dash, remove pre-conceptions of "situation" and let people rave on as they do in real life...The French movies of the 30's are still far superior to ours because the French really let their actors come on and the writers didn't quibble with some preconceived notion of how intelligent the movie audience is...American theater & Cinema at present is an outmoded dinosaur that ain't mutated along with the best in American Literature.

Excerpts from a letter written in late 1957 by Jack Kerouac to Marlon Brando. Brando never responded.

Al Cohn and Zoot Sims came up in the waning days of big-band jazz--they met in Woody Herman's Second Herd, where they were featured saxophone soloists, along with Stan Getz and Serge Chaloff. Sims and Cohn, both disciples of Lester Young's style, became lifelong friends (someone once called them the Damian and Pythias of jazz), playing together in various incarnations, ranging from a duo backing Kerouac to co-leaders of a quintet, until the 1980s. They died within three years of each other.

Their clarinet duet, "Two Funky People," is their friendship embodied in music. Cohn takes the first solo, cool and wistful, while Sims offers a more jovial response. Teddy Kotick on bass and the young Mose Allison on piano have their brief say, and then Sims and Cohn soar off stage. Nick Stabulas, on drums, quietly frames it all.

Recorded in New York on 27 March 1957 and released on the Verve LP Al and Zoot, my copy of which, as you will hear, is showing its age.

Brenda Lee's "Dynamite" shows how the little powerhouse (standing just 4' 9") earned her nickname. Lee, born Brenda Mae Tarpley in Atlanta in 1944, was able by age three to perfectly sing back a tune she had heard only once, and by five was winning talent competitions. After her father was killed in a construction site accident, Lee became the major breadwinner for her family, and was making records by her 12th birthday.

After making a few singles that didn't do much, Lee caught fire in 1957: she outsang Ray Charles on the man's own song ("Ain't That Love") while on "Dynamite" the chipper backing vocalists seem to be trying to distract the listener from Lee's white-hot vocal. Just try to not think about the disturbing fact that a 12-year old girl is howling about getting "one hour of love tonight."

Released as Decca 30333 c/w "Love You 'Til I Die"; on Anthology. Brenda setting off "Dynamite" live in 1957, and again in Japan in 1965.

The Cues were Atlantic Records' house vocal group, assembled by arranger Jesse Stone, and used for backup vocals on dozens of Atlantic records in the '50s, performing under a host of pseudonyms--they were the Rhythmakers for Ruth Brown, the Ivorytones for Ivory Joe Hunter, the Blues Kings for Joe Turner, the Boleros for Carmen Taylor and, for LaVern Baker, the Gliders (info from JC Marion's page on the group).

The group, which consisted of lead singer Jimmy Breedlove, Ollie Jones, Abel De Costa, Robie Kirk and Eddie Barnes, eventually branched out from Atlantic (they backed up Roy Hamilton on his glorious "Don't Let Go") and would occasionally cut a single of their own, with only middling success, although the fantastic "Why," which only hit #77 on the national charts, deserves far more recognition.

Released as Capitol 3582 c/w "Prince or Pauper"; on Golden Age of American Rock & Roll Vol. 10.

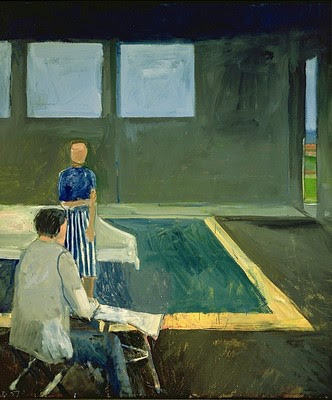

Diebenkorn, Man and Woman in a Large Room

Tommy Blake, if never a major rock & roll figure on the charts, certainly lived the life--enduring a hardscrabble childhood in Shreveport, losing an eye in Korea (or so he claimed) and shot to death by his wife on Christmas Eve, 1985. (What led to the latter is a source of contention--scroll down on this site for Rashomon-esque competing perspectives.)

"Lordy Hoody," one of the singles Blake cut for Sam Phillips in the late '50s, is rock & roll at its rawest and purest: slurred, incomprehensible lyrics; thudding bass; yelps and screams; war drums; utterly vicious lead guitar by Carl Adams; and a chanted, hypnotic nonsense chorus that likely inculcated any teenager in earshot.

Recorded 14 September 1957 and released as Sun 278 c/w "Flat Foot Sam"; on Koolit: The Sun Years Plus.

The Brazilian guitarist Bola Sete was born Djalma de Andrade in Rio in 1923 (in his youth, he got the nickname "Bola Sete," which is the Brazilian equivalent to the eight-ball, i.e., the only black ball on the billiard table--Sete was often the only black member of his early groups). Obsessed with the great guitarists of the Depression era--Reinhardt, Charlie Christian, Barney Kessel--Sete began playing in local samba groups, and by the '50s and '60s, after spending some years playing at upscale U.S. hotels like the Park Sheraton in NYC, was working with the likes of Vince Guaraldi and Dizzy Gillespie as well as leading his own trio.

Sete's version of Ary Barroso's "Aquarela do Brasil" showcases his soulful, intricate playing. Sete died in 1987, and is a bit of a neglected figure (few of his records ever made it to CD), though there seems to be renewed interest in his work of late.

"Aquarela" was recorded 8 February 1957 and released as Odeon 14254 c/w "Bacara", as well as on the '57 LP Aqui Está o Bola Sete. See Sete playing with a trio here.

Other versions of "Brasil," the country's unofficial national anthem: Joao Gilberto, Elis Regina, Carmen Miranda, Gal Costa, Daniela Mercury and Caetano Veloso, The Scorpions, José Carioca and Donald Duck.

Ozu's Tokyo Twilight

Al Simmons was the drummer of an obscure band called the Cats From Fresno, who recorded for Johnny Otis's Dig label. One day in the studio, the Cats decided to let Simmons take a vocal--"Old Folks Boogie" (a rewrite of several electric blues, including John Lee Hooker's "Gotta Boogie" and "Boogie Chillun" and Little Junior's "Feelin' Good") is the result, and it's a monster. It was one of Captain Beefheart's favorite tracks.

Released as Dig 138 c/w "Hand Me Down Baby" (sung by Sidney Maiden); on Teenage Rock N Roll Party. Thanks to the Rev. for introducing me to this one.

Magic Sam, born Samuel Maghett to sharecroppers near Grenada, Mississippi, in 1937, moved with his family north to Chicago as part of the great postwar black migration. In Chicago, Sam was a chawbacon--raw, uncouth, a bit wild. As a child he had crafted his own instruments, diddley-bows of baling wire nailed to the side of a barn, or makeshift guitars from cigar boxes, and in Chicago, when he began playing professionally, Sam took the same approach with his guitar style--taking the Delta blues and mixing it with what he was hearing in the clubs, especially records by Muddy Waters and B.B. King. (Much info from Greg Johnson's article linked above.)

Willie Dixon, by 1957, was sick of working for Chess Records, which he felt wasn't paying him enough and which seemed uninterested in the new blues players to hit Chicago, like Otis Rush and Buddy Guy. So Dixon and Eli Toscano, who was mainly known as a gambler, formed Cobra Records--described as a sort of shadow government to Chess, often signing the same artists Chess did and pushing its engineers to get a similar sound. The difference was Cobra also had a taste for young, hungry blues players.

"All Your Love," built off a riff from Ray Charles' recent "Lonely Avenue," was the first track Sam cut for Cobra, a single he recorded with Dixon, pianist Little Brother Montgomery, drummer Billie Stepney and Mack Thompson on bass.

By 1960, Cobra had folded and Sam had been drafted into the Army (he quickly deserted, and was eventually sent to military prison). After some hard years, Sam began building his reputation again, playing the Fillmore East and becoming a favorite of the new generation of blues players, when he died of a heart attack in 1969, at age 32.

Released as Cobra 5013 c/w "Love Me With a Feeling"; on West Side Soul.

Johnnie Wright and Jack Anglin, both from Tennessee, were one of several "brother" duet acts in country music who weren't actually brothers (though Anglin eventually married Wright's sister). While starting out offering fairly standard country fare, Johnnie & Jack began incorporating fresher sounds into their records--a Latin beat in "Poison Love," calypso in "Cryin' Heart Blues" and doo-wop in their cover of the Spaniels' "Goodnight Sweetheart." And "That's Why I'm Leavin'" is about as much rockabilly as it is straight country.

Anglin was killed in a car crash on the same day in 1963 that services were held for Patsy Cline, Hawkshaw Hawkins and Cowboy Copas, who had been killed in a plane crash (it was a horrific week for country music); Wright, who was married to Kitty Wells, continued on as a solo act and later became part of the Kitty Wells Family Show.

Released as RCA 6932 c/w "Oh Boy, I Love Her"; only available on this massive box set.

4th St, Santa Ana, Calif.

Henri Pousseur's "Scambi," an Ultima Thule of recorded music, is a series of electronic noises (some of which were first used by Stockhausen in his "Gesang der Jünglinge" a few years earlier), and also a completely "open" work--while Pousseur assembled the version here in the RAI Studio di Fonologia in Milan, in 1957, he intended the piece to be constantly reassembled and remastered. (The Scambi Project has documented these changes over the years.)

"Scambi" ("Exchanges") is alternately charming (some of the sounds resemble bird calls), terrifying, annoying and commonplace (some of the tones have become part of the 21st Century's background noise, reincarnated as cel phone beeps, ATM machine twits, etc).

On Anthology of Noise and Electronic Music Vol. 1.

Jenks "Tex" Carman was a bizarre figure in the '50s--a cowboy Hawaiian guitar player with a wayward sense of tuning and rhythm; he managed to record a few modest hits and appeared on regional television programs, sometimes wearing a cowboy hat, sometimes a headdress (he claimed to be part Cherokee). Carman vanished around the time JFK was elected, though at the end of the past century he was exhumed by hipsters and placed in various cabinets of curiosities (yours truly proving no exception).

"Wolf Creek" was one of the tracks Carman recorded for the small label Sage and Sand--released as Sage 251 c/w "My Broken Heart Won't Let Me Sleep"; on Cow Punk.

Jean Shepard routinely cast herself as the betrayed woman in her songs, which makes "The Other Woman" a shock: here, Shepard is the adultress, and she has no remorse over her actions. While sounding bold and fearless at first, Shepard's character reveals her delusions as the song goes on--she's terrified that her lover's wife will win him back, and by the end she is reduced to singing, like a child in a schoolyard, "he loves me, he loves me" over and over again until the fadeout.

Recorded 28 December 1956 and released as Capitol F3727 c/w "Under Suspicion"; on the shamefully out-of-print Honky Tonk Heroine.

Louise Brooks at age 50

The "5" Royales' "Say It" is one of their lost masterpieces, eclipsed by their '57 hit singles "Think" and "Dedicated To the One I Love." "Say It" conveys a simple, if sadly familiar situation--the singer knows it's all over with his lover, he can almost taste it, and all he wants now is for her to say the words. "Say it!" he demands, with the rest of the Royales backing him up--they grow more threatening with each reiteration. And each time he entreats her, Lowman Pauling's guitar delivers a squall of notes. The track ends with Pauling spiraling downward on his Les Paul: nothing is resolved: she still hasn't said it.

Recorded in Cincinnati on 13 August 1957 and released as King 5082 c/w "Messin' Up"; on It's Hard But It's Fair.

And in Jackie Lee Cochran's "Mama Don't You Think I Know," the singer doesn't even have to ask--he's figured it all out, and now he just wants her to get the hell out.

Released as Decca 9-30206 c/w "Ruby Pearl"; on That'll Flat Git It! Vol. 2

Finally, the pianist Ellis Larkins, accompanied by Joe Benjamin on bass, offers a reverie on "I Don't Stand a Ghost of a Chance With You." Larkins, a greatly underrated pianist whose elegant and gracious playing accompanied the likes of Ella Fitzgerald, Helen Humes, Eartha Kitt and Ruby Braff, was known in the '70s in New York for playing weekly at Gregory's, a club in the Upper East Side, and the Carnegie Tavern, a small bar behind Carnegie Hall.

His version of "Ghost of a Chance" was recorded in New York on 2 December 1957; on the Decca LP The Soft Touch (an album far more tasteful than its cover art) and never released on CD.

Happy Thanksgiving. And for the rest of the world, happy Thursday.