Columbia Orchestra, I Thought I Was a Winner, or, I Don't Know, You Ain't So Warm.

Silas Leachman, The Fortune Telling Man.

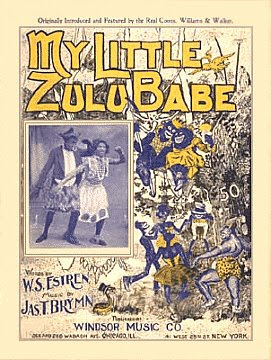

Bert Williams and George Walker, My Little Zulu Babe.

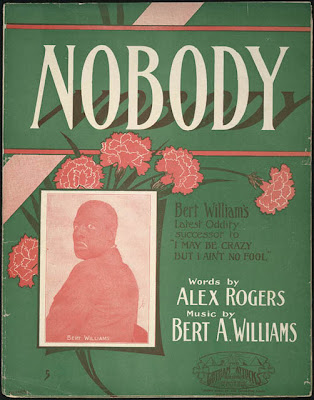

Bert Williams, Nobody.

Bert Williams, Let It Alone.

Bert Williams, Play That Barbershop Chord.

Nora Bayes, You Can't Get Away From It.

Bert Williams, You Can't Get Away From It.

Bert Williams, It's Nobody's Business But My Own.

Bert Williams, Elder Eatmore's Sermon On Generosity.

Louis Armstrong, Elder Eatmore's Sermon On Throwing Stones.

Bert Williams, Brother Low Down.

Bert Williams, Unlucky Blues.

Duke Ellington, A Portrait of Bert Williams.

Stick your patent name on a signboard

brother--all over--going west--young man

Tintex--Japalac--Certain-teed Overalls ads

and land sakes! under the new playbill ripped

in the guaranteed corner--see Bert Williams what?

Hart Crane, The Bridge.

Maurice Barrymore, patriarch of the famous and self-destructive acting clan (Drew's great-grandfather), was standing just offstage one night in New York, watching Bert Williams perform, trying to catch some of his tricks. A stagehand asked Barrymore what he thought of Williams. "Oh, he's terrific," Barrymore said. The stagehand nodded: "Yeah, he's a good nigger--knows his place."

Williams, walking offstage, heard the man. Passing by, Williams muttered, "Yes, a good nigger knows his place all right. Going there now. Dressing Room One!"

Al Frueh, Caricature of Bert Williams.

The funniest man I ever saw and the saddest man I ever knew.

W.C. Fields, on Bert Williams.

Spare a thought for the man in Dressing Room One. He dips a well-stained washcloth into a basin, then daubs his face, which is slathered in burnt cork. When the cloth first touches the makeup, the stain darkens deeper, for a moment, until, with a slow swipe, the man smears off his paint.

This is Bert Williams, a man cursed to forever break ground. First major black recording artist. First black performer to headline the Ziegfeld Follies (which led many Southern states to bar the Follies from performing in their cities). Leading man of the first black-written and composed Broadway musical. First black musician to star in a film. A life of constant revolution, and as such, a wearying one, one susceptible to unique strains of humiliations and frustrations.

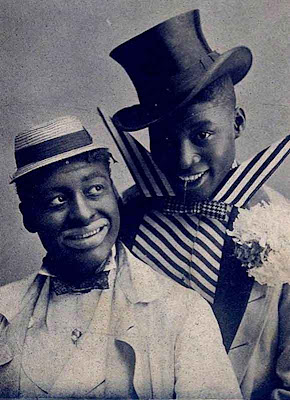

Egbert Austin Williams was born in 1874, in The Bahamas, and when he was ten his family relocated to California. By his late teens, Williams was singing in church choirs and minstrel troupes. He was an end man in the gloriously-named Martin & Selig's Mastodon Minstrels, where he met his future partner George Walker. Lithe where Williams was bulky, sharp where Williams played dull, Walker was his natural counterpart. By 1895, they were billing themselves as "Two Real Coons" (as opposed to all the white singers in blackface: it was around this time the lighter-skinned Williams--who had played a Hawaiian on stage--began blacking up) and a year later they were in New York, cakewalking to one of Williams' songs, "Oh I Don't Know, You Ain't So Warm," also known as "I Thought I Was a Winner."

(A recording of "Winner" was made by the Columbia Orchestra circa 1897, with white minstrel Len Spencer singing a chorus towards the end. Released as Columbia 15034; find in this archive.)

Williams and Walker at their peak, 1903

In 1901 Williams and Walker recorded for the first time, cutting a few songs for Victor. Since only about 500 to 1,000 discs of each performance were pressed, these early recordings are now quite rare and in some cases, such as the disc of Williams and Walker's own composition, "The Fortune Telling Man," are lost. What has survived of "Fortune Telling Man" is a contemporary recording by Silas Leachman, who has a screwy verve to his vocal and may provide a fairly accurate imitation of how the pair delivered the song.

(Recorded 12 December 1901 and released as Victor 1126; the collected Leachman recordings are here.)

One of the earliest surviving Williams and Walker tracks is "My Little Zulu Babe." It's a strange, ironic record--two black Americans singing a fantasy of "darkest Africa" (written by an African-American composer), complete with chants, wails, whinnies and moans. Walker sings the verses, Williams groans behind him, they harmonize at the end. A joke for black listeners, a taste of "exotica" for white ones. It sounded like nothing else recorded that year, or any other year, for that matter.

Recorded 10 or 11 November 1901 and released as Victor 1086.

Though he grudgingly wore blackface on stage, Williams had some boundaries: he would never perform or record the more vicious, racist songs of the period, so there are no Williams versions of "Bully of the Town" or "All Coons Look Alike to Me."

"Nobody," which Williams wrote with Alex Rogers and recorded in 1906, is his masterpiece, his calling card, his standard. It changed the game, irrevocably. As David Wondrich argues, "Nobody" helped kill off the white minstrel record business, despite the fact that "Nobody" had been first recorded by the white singer Arthur Collins. No one--Spencer, Collins, Leachman--could imitate what Williams did on his 1906 records: the expert phrasing, the sense of relaxed swing, the grit. (Eddie Cantor once described Williams' singing as "catching up with the melodic phrase after he had let it get a head start.")

"Nobody" is ostensibly a comic song, a gag piece. But listen to the artistry of Williams' singing, to the cold snap in his voice as he recounts the charity he never received, the way he starts the chorus mimicking the trombone that has entered a beat before him, and, in the final verse, the way his jester's smile fades, for a moment, when he says "not a soul." Williams later called his "Nobody" character "the Jonah man": the stoic victim of holy chance and eternal disappointment.

"Let It Alone," from the same year, is almost as good--hard truths delivered as wisecracks. And the brilliant "Play That Barbershop Chord," from 1910, finds Williams in high form: singing the verse with a sense of sly gentility, resting where the music wants him to move forward, throwing in an extra phase just when the ear isn't expecting it.

"Nobody" was released in June 1906 as Columbia 3423/33011; "Let it Alone" as Columbia 3504, and "Chord," recorded 11 July 1910, as Columbia 929.

In truth, I have never been able to discover there was anything disgraceful in being a colored man. But I have often found it inconvenient--in America.

Bert Williams, The American Magazine, January 1919.

George Walker, a notorious ladies man, had contracted syphilis and died in 1911 (Carl Sandburg later wrote, in an early bit of hipster oneupmanship, "I heard Williams and Walker/before Walker died in the bughouse"). Williams dutifully supported Walker during his decline, but his own prospects soared as he left Walker's orbit. He was a Ziegfeld headliner, and a top-selling recording artist for Columbia.

Many of Williams' records from the early '10s, however, aren't that compelling. Columbia, for whom he had become a mainstay, wanted him to basically re-cut and rewrite "Nobody" every few years ("Unexpectedly," "Somebody," "Constantly," etc), while also dashing out whatever trendy piece was at hand.

So in 1914, when pop songwriters were trying to cash in on the ragtime craze, Williams recorded one of the more inspired attempts, William Jerome and Jean Schwartz's "You Can't Get Away From It." A month before, however, the Broadway star Nora Bayes cut her own version, and she may have trumped Williams for once. Bayes, who in the course of the song flits from street to high-society accents, seems besotted with the freedoms the song offers; she takes delight in the intricate rhymes and the absurdity of the concept. Williams, by contrast, sounds tired, restrained, a bit bemused. Really, what in hell is going on these days? he wonders.

(Bayes' version was recorded 22 January 1914 and released as Victor 60114; Williams', rec. 4 February 1914, was Columbia 1504.)

Williams' talents as a raconteur and caricaturist were rarely found on record, until in 1919, when Williams cut his two "Elder Eatmore" sermons, which he co-wrote with "Nobody" lyricist Alex Rogers.

Williams' Elder is a bumbling, malapropism-ridden clergyman who's out mainly to line his own pockets ("If somethin' ain't done/your shepherd is gone!"). Some have found the records to be a mockery of African-American religion in general, but it's fairer to say they're a satire of a specific type--Pentecostal/Holiness churches, which accompanied the great exodus of Southern blacks to Northern cities. To an urbanized, cultured man like Williams, the new ministers likely seemed baffling and a bit ridiculous. (In 1915, the African-American pastor of the mainline Olivet Baptist Church warned about the new migrants wanting "enthusiastic" services--"[I do not] countenance a church of daemonic pandemonium.")

The Elder Eatmore disc sold more than 185,000 copies (it was a 12" disc, so that Williams had more than four minutes to cook his monologues), and was treasured by the following generation of black comedians and singers. In the '30s, Louis Armstrong remade both of Williams' sermons, with Harry Mills, of the Mills Brothers, on organ (included here is their 1938 take on "Eatmore's Sermon on Throwing Stones"), while the Elder reemerged as "Deacon Jones" in the '40s and '50s, in a string of R&B hits. Only when the civil rights movement began, with Southern black ministers as the leading actors of the struggle, did the image of "Elder Eatmore" at last fade into oblivion.

Williams making one of his final recordings, ca. 1920.

All the jokes in the world are based on a few elemental ideas....Troubles are funny only when you pin them down to one particular individual. And that individual, the fellow who is the goat, must be the man who is singing the song or telling the story....It was not until I could see myself as another person that my sense of humor developed. For I do not believe there is any such thing as innate humor. It has to be developed by hard work and...I have studied it all my life.

Bert Williams, 1918.

Some of the records Williams cut in his last years have a sense of fresh possibilities. There's a new gravity to Williams' singing, a swaying movement towards the blues, while Williams hones his skill at portraiture. He continued to play the false preacher: "It's Nobody's Business But My Own," from 1919, is a variation on the Eatmore sermons, while "Brother Low Down" finds Williams on the street corner offering salvation and keeping his hand out for a stray dollar.

"Unlucky Blues," from 1920, seems at first listen to be yet another "Nobody" sequel. However, there's an autumnal richness to this performance, a sense of weary summation. The Columbia house orchestra backing Williams isn't much: most of the time, they seem to be playing in the next room. But Williams' vocal is imbued with experience, marveling at the things he's seen and the woes he's suffered, while his bluesy growl conjures up the future voice of Louis Armstrong.

("Nobody's Business" was Columbia 2750, "Unlucky Blues" (thrown away as the b-side of "Ten Little Bottles") was Columbia 2941, and "Brother Low Down," one of the last tracks Williams cut in his life, was Columbia 3508.)

Bert died--just about--on stage. Suffering from a bad heart, neuritis and pneumonia, Williams collapsed while performing one night in Detroit. He was taken off stage, but asked to go back out again. Afterward, they laid him out on a couch in his dressing room, where Williams said: "That's a nice way to die--they were laughing at my last exit." He made it back to New York, where he died on March 4, 1922.

He was only 47. Had he been granted only five more years, we could have had Williams singing "Nobody Knows You When You're Down and Out," or have had Louis Armstrong and Sidney Bechet back him up, or Duke Ellington arrange a piece for him (Ellington's 1940 tribute to Williams conjures up Williams' ghost as a sly shadow, dancing off stage). Imagine Williams biting into a new Gershwin or Hoagy Carmichael song, or duetting with Mamie Smith or Ethel Waters.

It wasn't to be. He had lived out in the wilderness, and you could say he died a day's walk from the city. His children would have gratefully carried him there.

Recordings: Love Bert Williams now? The essential Bert Williams collection has been assembled by Archeophone, which offers his complete works in three discs: 1901-1909, 1910-1918 and 1919-1922. Document Records has some later-period Williams records via eMusic, though Document seems to have unearthed the scratchiest recordings imaginable. (Some Williams tracks are found in this public domain archive as well.) Armstrong's "Elder Eatmore" is on Jeepers Creepers. Ellington's tribute, from 1940, is on this compilation.

Sources: Camille Forbes, Introducing Bert Williams: Burnt Cork, Broadway and the Story of America's First Black Star; Tim Brooks, Lost Sounds; David Wondrich, Stomp and Swerve; Gary Giddins, Visions of Jazz; Teresa Reed, The Holy Profane (on the life and legacy of Elder Eatmore).

Note: This occasional series was originally going to be called "The Locust St. Hall of Fame" until my acute sense of modesty prevailed. A "songster," according to the collector Howard Odum in 1911, is someone "who regularly sings or makes songs," which seems plain enough. Paul Oliver, many years later, added that songsters "were receptive to a wide variety of songs and music; priding themselves on their range, versatility and capacity to pick up a tune, they played not only for the black communities, but for the whites too, when the opportunities arose. Whatever else the songster had to provide in the way of entertainment, he was always expected to sing and play for dances." These are modern songsters, though, so the rules don't always apply, unless they do.

Next: Nailed to the North Pole.