John McCormack, It's a Long Way to Tipperary.

Irving Berlin, Follow the Crowd.

James Reese Europe's Society Orchestra, Down Home Rag.

James Reese Europe's Society Orchestra, Castle House Rag.

Joan Sawyer's Persian Garden Orchestra, Bregeiro.

Van Eps Banjo Orchestra, Sans Souci (Maxixe Bresilienne).

Victor Military Band, Memphis Blues.

Felix Arndt, Desecration Rag (A Classic Nightmare).

Unknown Band, 20th Century Rag.

The reservists were leaving for London by the nine o'clock train. They were young men, some of them drunk. There was one bawling and brawling before the ticket window; there were two swaying on the steps of the subway shouting, and ending, "Let's go an' have another afore we go." There were a few women seeing off their sweethearts and brothers. One woman stood before the carriage window. She and her sweetheart were being very matter-of-fact, cheerful and bumptious over the parting.

"Well, so long!" she cried as the train began to move. "When you see 'em let 'em have it."

"Ay, no fear," shouted the man, and the train was gone, the man grinning.

I thought what it would really be like, "when he saw 'em."

Last autumn I followed the Bavarian army down the Isar valley and near the foot of the Alps. Then I could see what war would be like--an affair entirely of machines, with men attached to the machines as the subordinate part thereof, as the butt is the part of a rifle.

D.H. Lawrence, Manchester Guardian, 18 August 1914.

"It's a Long Way to Tipperary," a 1912 show tune by Jack Judge and Harry Williams, became the British theme song for four catastrophic years; it was cut several times during the war--a 1914 recording by John McCormack is here, along with Billy Murray and Albert Farrington's versions.

We only know Irving Berlin through his interpreters, whether Bing Crosby or Ethel Merman, so the sound of Berlin's front-parlor singing voice can startle. You can sense in Berlin's raw, humble vocal the vast reservoir of energy that powered his compositions--the sense of optimism and pluck that makes even a call to mass conformity (as in "Follow the Crowd") swing.

"Follow the Crowd" is basically a rewrite of "Alexander's Ragtime Band," with the singer once again trying to entice someone out of their house and into the street (the pitch includes the prospect of seeing, and joining, "thousands of dreamy tango dancers!!"). Written for the show The Queen of the Movies, which opened in January 1914.

Berlin recorded "Follow the Crowd" for Columbia in January 1914, but the track was never released (not surprising, as it's basically a demo); it finally appeared on a 1980s compilation entitled Music for the New York Stage Vol. 3 and can now be found in this archive. "Crowd" and other Berlin performances are on Irving Sings Berlin.

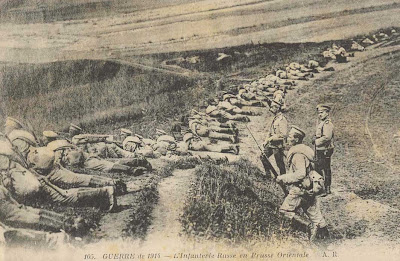

Czech volunteers for the Russian Army, ca. 1914-1915

Soon [the trains] would be moving, filled with hundreds of thousands of young men making their way, at ten or twenty miles an hour and often with lengthy, unexplained waits, to the detraining points just behind the frontiers...

Images of those journey are among the strongest to come down to us from the first two weeks of August 1914: the chalk scrawls on the waggon sides--"Ausflug nach Paris" and "à Berlin"--the eager young faces above the open collars of unworn uniforms, khaki, field-grey, pike-grey, olive-green, dark blue, crowding the windows. The faces glow in the bright sun of the harvest month and there are smiles, uplifted hands, the grimace of unheard shouts, the intangible mood of holiday, release from routine.

The Germans marched to war with flowers in the muzzles of their rifles or stuck between the top buttons of their tunics; the French marched in close-pressed ranks, bowed under the weight of enormous packs, forcing a passage between crowds overspilling the pavements...Russian soldiers paraded before their regimental icons for a blessing by the chaplain, Austrians to shouts of loyalty to Franz Joseph...

Battle of the Marne

However clothed, the infantrymen of every army were afflicted by the enormous weight of their equipment: a rifle weighing ten pounds, bayonet, entrenching tool, ammunition pouches holding a hundred rounds or more, water bottle, large pack containing spare socks and shirt, haversack with iron rations and field dressing...The French piled everything into a mountainous pyramid, le chargement de campagne, crowned with the individual's metal cooking pot; gleams of sunlight from such pots would allow young Lieutenant Rommel to identify and kill French soldiers in high standing corn on the French frontier later that August.

John Keegan, "The Battle of the Frontiers and the Marne," The First World War.

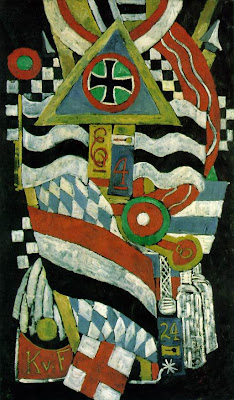

Hartley, Portrait of a German Officer

The short, extraordinary life of James Reese Europe seems crafted to fit the demands of history. His colleague Eubie Blake once called him the "Martin Luther King of music," and while that seems hyperbolic, there is something epic to the man: Europe would reconcile in his own person the extremes of the conservatory and the street, and he invented or popularized, among other things, the turkey trot, the foxtrot, and the word "gig" to denote a musical performance (or so Blake claimed).

One of the first major African-American bandleaders, and the first black bandleader to have a recording contract, Europe drafted the big-band future (he serves as the dry run for Duke Ellington) by making a patchwork of the recent past, taking freely from ragtime, blues, classical piano recitals, brass bands, even novelty minstrel cylinders, so that everyone from Benjamin Harney to Will Marion Cook to Scott Joplin to W.C. Handy seems to have held equity in him.

Europe's Society Orchestra, 1914 (Europe is at the piano)

Europe was born in 1881 to a freedman minister and a freeborn schoolteacher, both of whom were also musicians, and Europe grew up in the emerging, aspiring black middle class of Washington DC that would later produce Ellington. Europe trained with John Philip Sousa's assistant director, learned violin and piano, and moved to New York after he graduated high school. Like his predecessors Joplin and Cook, he found no interest in his classical ambitions, so he switched to mandolin and wrote songs for dance revues, with some success. In 1910 he founded, along with some colleagues, the Clef Club, an all-purpose organization that served as concert promoter, booking agency, informal union for black musicians and, for Europe, composition and arrangement laboratory. By 1912, the Clef Club Symphony Orchestra was playing Carnegie Hall.

The dance team of Irene and Vernon Castle, having seen Europe's band perform at a private party, hired him and his orchestra as their house band, and so in 1913-1914, the Castles quietly and smoothly integrated society music. If you wanted to book the Castles, the hippest dancers in town, you had to hire their black musicians too, because the Castles demanded it in their contracts. (Sometimes their solutions were ingenious--when a New York musician's union complained about having black musicians play in the orchestra pit, the Castles simply moved Europe's band on stage.)

Soon enough, Europe's band got a contract from Victor, and some of their first records, in particular "Down Home Rag" and "Castle House Rag," are stunning. One of Europe's key weapons was his drummer, Buddy Gilmore, who is arguably one of the first drummers to even be heard on record, let alone a dominant, freewheeling one who sounded like he was firing a machine gun.

For their version of Wilbur Sweatman's "Down Home Rag," the Europe Orchestra basically keeps to the written score, but the vitality of the performance breaks through the record's sonic limitations--listen to the way Gilmore's drum fills spur hollers from the band, or the way the band wheels along at a frenetic pace (twice as fast as other contemporary recordings of this piece, like the Six Brown Brothers'). One trick Europe used was to over-egg the mix, as his records feature "walls of sound"--there are five banjo-mandolin players, two pianos, three violinists, among others, all crammed into the track until it bursts. The result is, as Reid Badger wrote, in A Life in Ragtime:

There is a clear sense in this first Europe recording that interpretation is at least equal in value to composition. How something is played is as important as what is played, especially if that something is intended for dancing. (itals mine)

"Castle House Rag," also known as "Castles in Europe," goes further out--it is a viable candidate for the first jazz recording. While the piece is assembled according to the set four-strain AABBACCDD ragtime pattern, and the first three strains are fairly standard, the fourth strain breaks apart, suggesting to some that Europe basically let his band go off the charts and improvise, until the piece ends with a battle between Cricket Smith's cornet and Gilmore's drums.

Europe's Society Orchestra was: James Reese Europe directing Smith (cornet), Edgar Campbell (cl) Tracy Cooper, George Smith, Walter Scott (v), Leonard Smith, Ford Dabney (p), five banjo-mandolin players, including Noble Sissle, and Gilmore (d). In the 1914 session, Europe added Chandler Ford on cello, a baritone horn and flute, and ditched the banjo-mandolins.

"Down Home Rag" was recorded on 29 December 1913 and released as Victor 35359 c/w "Too Much Mustard"; "Castle House Rag" was cut on 10 February 1914 and released as Victor 35372, c/w "Castle's Lame Duck"; find here.

We are just getting up when mother comes up to me and says, "Vonet! Vonet! Put your soldiers away, the Germans are coming!" I go outside after putting them away and I hear shooting and I see a plane in the sky. As soon as I am back inside, my big brothers come through the door. "They're coming! They're right behind us!" I go and look out the dining-room window.

They pass by the window and we hear a gruff command: 'aarrarrrncharr." They stop and line up to go to the station, when the shooting starts. They turn around and charge. Some fall down and we hear a thud--two massive ones even, as two horses fall dead in front of the window. Bullets whiz by in both directions. We go into the living room and we hear Germans hitting Mr. Benoit's door with their rifle butts, looking for French troops. Just to be safe they shoot Mr. Benoit's dog, so that its barking won't interfere with their patrols.

Diary of Yves Congar, 10-year-old native of Sedan, a northeast French town that fell to the German army on 25 August 1914.

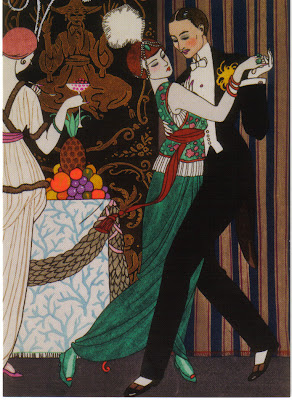

Klinger, "Spring Show" poster.

Joan Sawyer was born Bessie Morrison in Cincinnati, in 1880 (she took her stage name from an ex-husband), and she scrapped for fame for much of her life, mostly on the vaudeville stage, though much of her notoriety came from a breach-of-promise lawsuit she filed against a playboy she claimed had backed out of marrying her.

Around 1911, she became an exhibition dancer, positioning herself as an elegant "high society" contrast to the modernist Castles. She persuaded the theater mogul Lee Shubert to back a new dance club for his Winter Garden theater--Joan Sawyer's Persian Garden, which opened in January 1914. There Sawyer greeted each patron and danced the latest steps with a series of partners (including the young Rudolph Valentino). And like the Castles, she was backed by her own private orchestra of black musicians. (Much of this is from Tim Brooks' Lost Sounds.)

Sawyer's would-be James Europe was Jamaica-born Dan Kildare, who ran the Clef Club Orchestra after Europe had left to form his own group. With the Castles/Europe Society Orchestra tracks selling well for Victor, Columbia quickly signed the Castles' main competition--Sawyer and the Clef Club Orchestra.

The Sawyer tracks aren't of the same caliber as the early Europe cuts, however, and they were also duds in the marketplace (so much that Columbia shelved some of the tracks because of poor initial sales); the best of the bunch was the Clef Club Orchestra's take on Ernesto Nazareth's classic "Brejeiro," a mandolin-led maxixe, a performance whose tight rhythmic interplay is highlighted by unusually clear sound for the period.

Recorded in New York on 6 May 1914 and released as Columbia A5572; on The Earliest Black String Bands Vol. 1.

The banjo monarch Vess Ossman was finally toppled in the 1910s by his younger rival, Fred Van Eps. Van Eps had worshiped Ossman (he had improved his banjo technique by playing Ossman cylinders over and over again, and his first recording sessions were often remakes of Ossman tracks) so his triumph over his mentor has a touch of the Freudian to it, though some of it was logistical: Ossman had left New York around 1910, leaving Van Eps as the go-to studio banjoist for all the major record labels.

Ossman also seemed unable or unwilling to adapt to the changing times--while Ossman could do ragtime, he showed little interest in the more intricate and frenetic musics of the late 1910s, from jazz to various Brazilian dance imports. Ossman died in semi-obscurity in 1923, while Van Eps was still busy in the studio. (from Wondrich's Stomp and Swerve).

In the mid-'10s, Van Eps created a "banjo orchestra," a modest creature made up only of Van Eps and another banjoist, a pianist (often Felix Arndt, see below) and percussionist. Here is their take on another maxixe*, although "Sans Souci" is not a Brazilian import but rather a knock-off by songwriter Arthur Green.

Recorded 24 July 1914 and released as Columbia A1594; on Stomp and Swerve.

* The maxixe, an enormous dance fad in 1914, was on the verge of taking over the United States until it suddenly fell into oblivion, seemingly overnight. No one seems to know why for sure (though the maxixe was reincarnated in the '30s as the carioca), but this fascinating article by Micol Seigel, "The Disappearing Dance: Maxixe's Imperial Erasure," has a number of theories.

That night your great guns, unawares,

Shook all our coffins as we lay,

And broke the chancel window-squares,

We thought it was the Judgment-day

And sat upright. While drearisome

Arose the howl of wakened hounds:

The mouse let fall the altar-crumb,

The worms drew back into the mounds,

The glebe cow drooled. Till God called, “No;

It’s gunnery practise out at sea

Just as before you went below;

The world is as it used to be:

“And all nations striving strong to make

Red war yet redder. Mad as hatters

They do no more for Christ's sake

Than you who are helpless in such matters."

Thomas Hardy, "Channel Firing," 1914.

Refugees, Ostend

History and authenticity rarely coincide. So the first-ever recording of the blues was not made by a Mississippi Delta musician, or by a New Orleans string band, or by a vaudeville pro, or even by the blues' composer, W.C. Handy. Instead, Handy's "Memphis Blues" was cut in New York by the anonymous, stodgy Victor Military Band, the house studio group of Victor Records.

And the record's a bit of a mess--whatever vitality the track suggests in its opening bars is soon eroded by some dithering percussion and a general turgidity to the playing. Still, in the third strain, buried underneath the stiff horns and the sludgy beat, is the primal I-IV-V blues chord sequence, the genetic code for the musical century to come.

Handy composed "Memphis Blues" ca. 1909 and copyrighted it in 1912. Was it the first blues ever written? Of course not.

A minor tragedy is that although James Reese Europe was among the first bandleaders to play "Memphis Blues" (and his band's version, according to those who heard it, was smoking), he never recorded it. As Wondrich wrote, the Europe Society Orchestra's "Memphis Blues" "is one of the greatest records that never got made."

The Victor Band track was recorded 15 July 1914 and released as Victor 17619 (Columbia cut a version a few days later by Prince's Band); in this archive.

3rd August: At school the teachers say it is our patriotic duty to stop using foreign words...you must no longer say "Adieu" because that is French. I must now call Mama "Mutter." People wander through the streets in groups, shouting "Down with Serbia! Long live Germany!"

10th September: Horror stories. They say Russians tie German women to trees, then set up wooden crosses in front of them and nail their little children to them. When the kids have died before their mother's eyes, the Russians mutilate the women and kill them. The Belgian guerrillas are said to be no better, but they do it all more secretly. Dear God, just bring the war to an end! I don't look on it as glorious any more, in spite of school holidays and victories.

16th September: Last night I heard Grandma crying. She was crying so much it greatly distressed me. The young First Lieutenant Schön is the first of our friends to be killed. I buried my head in the pillow so that Grandma would not hear me crying.

25th October: There is war everywhere. In Africa too. In the Orange Free State and the Transvaal a rebellion has broken out. There is nothing in the papers about our losses.

1914 diary of Piete Kuhr, a twelve-year-old girl in the East Prussian town of Schneidemühl (today known as Piła, in northwest Poland).

Russian Army, invasion of East Prussia

The pianist Felix Arndt, a descendant of Emperor Napoleon III, is a one-man intersection of classical piano, ragtime, jazz and what would be called "novelty ragtime," a lesser variant of ragtime popular in the late '10s and early '20s.

His "Desecration Rag"'s title is an in-joke, as the piece performs "ragtime perversions" (as Victor Records called them) on Dvorak's "Humoresque," Lizst's "2nd Hungarian Rhapsody," Sinding's "Rustle of Spring" and Chopin's "Impromptu," "Militaire Polonaise" and "Funeral March."

As Arndt was a New York-based piano player, his recordings may show the influence of the undocumented generation of regional pianists who were turning ragtime into stride jazz playing, such as New York's Richard "Abba Labba" McLean, Baltimore's "One Leg" Willie Joseph and John "Jack the Bear" Wilson, who played in Baltimore and NYC, and whose piano playing was a sideshow to his main interests of pimping, gambling and, later, opium.

Arndt was the organist at New York’s Trinity Church and a staff musician for the Duo-Art piano company, for whom he made some 3,000 piano roll recordings over a handful of years. He inspired and likely taught the young George Gershwin, and he died in October 1918, one of the millions of people killed by the Spanish flu pandemic, one of the 20th Century's less-remembered catastrophes.

"Desecration Rag" was recorded on 6 March 1914 and released as Victor 17608.

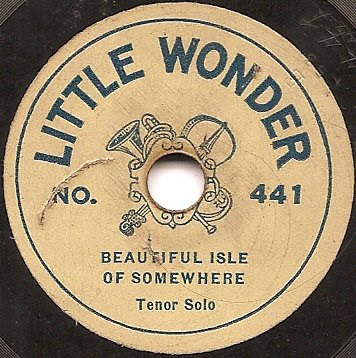

In October 1914, a man named Henry Waterson placed an ad in a pair of music trade magazines. Waterson, who was Irving Berlin's business partner and song publisher, proposed the following: "A New Low-Priced Record."

In 1914, there were only three major record labels, a quasi-monopoly: Edison (the eldest and weakest), Victor and Columbia. As the trio owned most of the record-manufacturing patents and had complete control over record distribution, they had no serious competition, and so were able to jack up prices, with the cheapest discs going for 65 cents (over $13 in today's dollars) and higher-end records selling for as much as an inflation-adjusted $20.

Waterson's "Little Wonder" Records proposed something new--keep it short and keep it cheap. The label produced 5 1/2-inch records, whose performances were, at most, two minutes in length, and Little Wonder sold them for a dime. It was all incredibly cut-rate: Little Wonders didn't credit artists on their labels, and their discs didn't even come in sleeves. Using a retail network of dime stores and catalogs, Little Wonder sold more than 20 million copies from 1914 to 1916 alone.

Bomberg, The Mud Bath

As it turns out, Little Wonder was secretly backed by Columbia, which offered up its recording artists (like Jolson and Eddie Cantor) for double-duty and pressed the Little Wonder records at its own plants. A lawsuit in 1916 led to Little Wonder being owned outright by Columbia, and by the early '20s, when Little Wonder folded, it was a far different world: Edison was in a permanent decline, record prices were cut to fit a working man's salary, a wider variety of retailers were selling records and, with the expiration of various patents, a host of new independent labels had started up.

So here's to Little Wonder, unsung democratizer of pop music. This is one of their first discs, cut sometime in 1914--"20th Century Rag," by some unknown group, released as Little Wonder 9. From the Little Wonder Music Library, which has a goldmine of Little Wonders. You can spend all day in there, as I did.

The Christmas truce, December 1914

The war goes slowly as death because it is death, death to millions of men. We've all said all we know about it to one another a thousand times: nobody knows anything else; nobody can guess when it will end: nobody has any doubt about how it will end....

Europe is ceasing to be interesting except as an example of how-not-to-do-it. It has no lessons for us except as a warning. When the whole continent has to go fighting--every blessed one of them--once a century, and half of them half of the time between, and when they shoot away all their money as soon as they begin to get rich a little, and everybody else's money too, and make the world poor, and when they kill every third and fourth generation of the best men and leave the worst to rear families, and have to start over fresh every time with a worse stock--give me Uncle Sam and the big farm! We don't need to catch any of this European life...Besides, I like a land where the potatoes have some flavor, where you can buy a cigar, and get your hair cut and have warm baths.

Letter of Walter Hines Page, U.S. ambassador to Britain, to his son; London, 20 December 1914.

Next: Planes and Lines.