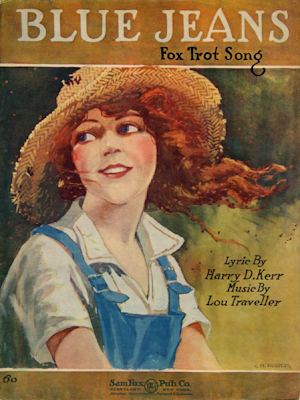

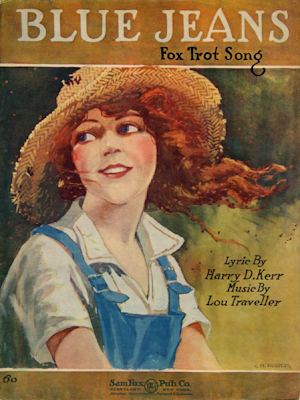

Paradise Is Just a Curse, 1920 Maurice Burkhart, It's the Smart Little Feller Who Stocked Up His Cellar That's Getting the Beautiful Girls.

Maurice Burkhart, It's the Smart Little Feller Who Stocked Up His Cellar That's Getting the Beautiful Girls.

Van and Schenck, All the Boys Love Mary.

Mamie Smith's Jazz Hounds, Crazy Blues.

Louisiana Five, Weeping Willow Blues.

Paul Whiteman and His Orchestra, Wang Wang Blues.

Frank Crumit, My Little Bimbo Down on the Bamboo Isle.

Isham Jones and His Rainbo Orchestra, When Shadows Fall I Hear You Calling.

Isham Jones and His Rainbo Orchestra, Wait'll You See.

Ezra Pound, Hugh Selwyn Mauberley (excerpt).

Charles Ives, Piano Sonata No. 2: The Alcotts.Section 1. After one year from the ratification of this article the manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors within, the importation thereof into, or the exportation thereof from the United States and all territory subject to the jurisdiction thereof for beverage purposes is hereby prohibited.

Section 2. The Congress and the several States shall have concurrent power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.The Eighteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States, which went into effect on 16 January 1920. Go raise a glass to unintended consequences.

Last call (for 13 years), 15 January 1920, Chicago.

Last call (for 13 years), 15 January 1920, Chicago.Prohibition-era dating tips blossomed in the record shops and on the stage. The key point, emphasized variously, was that regardless of how old or homely you were, if you had access to booze, your prospects were solid.

Viz.: Maurice Burkhart's "It's the Smart Little Feller Who Stocked Up His Cellar..." (

Edison Blue Amberol 3961/Edison Record 7039) or Van & Schenck's "All the Boys Love Mary" (because her old man's a bootlegger) (

Columbia A2942).

Annual Bathing Girl Parade, Balboa Beach, Calif., June 1920 (See Shorpy for the entire photo)

Annual Bathing Girl Parade, Balboa Beach, Calif., June 1920 (See Shorpy for the entire photo)

See, she was the first of all of us...Mamie's the one that paved the way over there. Then we came behind her.Victoria Spivey.

One Tuesday in New York City in August 1920, on

West 45th Street, Mamie Smith and a pickup studio group dubbed the Jazz Hounds cut "Crazy Blues," a record now freighted with history. It may be the first "true" jazz vocal record, or the first proper blues; its performer was the first African-American female singer on record, and its success at last convinced record companies that black artists could sell. It's little surprise the record is in

museum display cases. Stamped by the epochal, "Crazy Blues" still retains a bite despite its ninety years and its near-deification--it's the spiritual ancestor to everyone from Robert Johnson to Slick Rick:

I'm gonna do like a ChinamanGo and get some hop,Get myself a gunAnd shoot myself a cop.I ain't had nothing but bad news,Now I got the crazy blues.It's as though threads running through the first two decades of the 20th Century were at once tied in a tailor's knot: the seasoning of the vaudeville stage, the ambitions (and frustrations) of black composers, the growth (post-

Little Wonder) of independent record companies, the influx of black Southerners into Northern cities, the influence and the disciples of the late James Reese Europe.

Mamie the First: the blues' original monarch

Mamie the First: the blues' original monarchOur players:

Perry "Mule" Bradford was a jobbing songwriter and pianist, a former minstrel show performer, who in the late 1910s was trying to convince a record company to use his blues compositions and to hire a singer he represented named Mamie Smith. He was known in the record industry as a "striver," his nickname owed to his perseverance:

I'd schemed and used up all of my bag of tricks to get that date; had greased my neck with goose grease every morning, so it would become easy to bow and scrape to some recording managers. But none of them would listen to my tale o' woe, even though I displayed my teeth to them with a perpetually-lasting watermelon grin. (Bradford, recalling the first Mamie Smith session, in his autobiography

Born With the Blues.)

Mamie Smith, who was born in Cincinnati and who made her name in Harlem, was an imposing woman with costly tastes (at her peak, she allegedly owned two apartment houses and wore a $3,000 cape, trimmed with ostrich feathers, while on stage). Smith was not a blues singer by trade, as she never worked the medicine shows where Ma Rainey, for instance, had cut her teeth. Smith was more akin to Nora Bayes, Sophie Tucker or Ethel Waters: a sharp vaudeville pro, adept in a variety of styles, including the blues.

Buster Keaton and Sybil Seely in One Week

Buster Keaton and Sybil Seely in One Week.

Bradford got an audience with Otto Heinemann, who ran the fledgling OKeh label ("OKeh" is Otto K. E. Heinemann's initials), and his recording director, Fred Hager. They liked Bradford's songs but wanted Sophie Tucker to sing them. Tucker, however, claimed a contractual obligation, so OKeh agreed to give Smith a shot.

Smith's first record (and the first-ever solo black female vocal on disc) was the rather staid "That Thing Called Love," in which Smith was backed by OKeh's house band, the all-white Rega Orchestra. It sold well enough, so OKeh asked Smith to cut some more sides. Bradford had a popular song called "Harlem Blues," which Smith was singing on stage at the time. Before the session, he rewrote it and renamed it "Crazy Blues."

Höch, Pretty Maiden.

Höch, Pretty Maiden.For the "Crazy Blues" session, Bradford somehow convinced OKeh to use his own band, one Bradford had pieced together (in part from James Reese Europe's Hellfighters) that consisted entirely of African-American players, including the master pianist Willie "The Lion" Smith, the sparkplug cornet player Johnny Dunn, and Dope Andrews on trombone. According to Bradford, Hager, supervising the session, got nervous and asked him to be sure the band played "sweet" and "light". One can imagine Bradford nodding fervently, and once Hager was out of the room, turning to the band with his trademark grin and counting off. (That said, Bradford certainly embellished this story--it's hard to imagine pros like Hager or his engineer,

Ralph Peer, getting hoodwinked into recording hot jazz.)

Bradford described the session years later:

As we hit the introduction and Mamie started singing, it gave me a lifetime thrill to hear Johnny Dunn's cornet moaning those dreaming blues and Dope Andrews making some down-home slides on his trombone...Man, it was too much for me.Some critics have argued that "Crazy Blues" isn't really jazz (and is more a dressed-up show tune) but in any case it's masterful: Dunn, one of the first "individualist" horn players (he's something like the dress rehearsal for King Oliver and Louis Armstrong, playing with presence and a clear, distinct tone) sings above Andrews' swaying trombone, Ernest Elliot (clarinet) and Leroy Parker (fiddle) create an eerie wailing high end, while "The Lion"'s piano grounds Mamie's vocal.

"Crazy Blues" was released in November, and in its first month sold 75,000 copies at $1 a pop (so inflation-adjusted, the record earned roughly $700,000 in one month--OKeh soon cleared a million bucks off of it). Bradford later claimed that Pullman porters bought the record by the dozens and resold them at double the price to rural Southerners along their train routes. Alberta Hunter recalled what it was like after the disc hit: "

You couldn't walk down the street in a colored neighborhood and not hear that record. It was everywhere."

The cornerstone: "Crazy Blues" was recorded in New York on 10 August 1920 and released as OKeh 4169-A, c/w a lesser Bradford composition, "It’s Right Here For You (If You Don’t Get It ‘Taint No Fault O’ Mine)". On

Crazy Blues.

Mamie Smith’s and "Crazy Blues"' history is derived from many sources: Bradford's

Born With the Blues, Chris Albertson's

Bessie, Adam Gussow's

Seems Like Murder Here, Giles Oakley's

The Devil's Music, David Wondrich's

Stomp and Swerve, Samuel Charters and Leonard Kunstadt's

Jazz: A History of the New York Scene.

Bonus trivia note: Perry Bradford helped invent rock & roll too, writing Little Richard's "Keep a-Knockin'".

Sheeler, Church Street El.

Sheeler, Church Street El.Here's another dose of prime early New Orleans jazz from the Louisiana Five, dominated by "Yellow" Nuñez's clarinet. The Five's records of the period seem to be funeral rites for ragtime--Nuñez and his crew tumbling the music into its next incarnation.

"Weeping Willow Blues," recorded January 1920, was released as Emerson 10172; on

Ragtime to Jazz Vol. 2.

Paul Whiteman

Paul Whiteman was the mustached, moon-faced regent of jazz in the 1920s: his features seem crafted for Art Deco caricature. He was a Denver-born classical violinist who cast his lot with pop music, moving to San Fransisco, forming a dance band and trying to outplay Art Hickman. In 1920 Whiteman brought his orchestra to New York, contracted with Victor Records and became a centrifugal point of popular music. He hired Bix Beiderbecke, Jack Teagarden, Joe Venuti, Bing Crosby and Mildred Bailey, commissioned Gershwin's

Rhapsody In Blue, and had 28 #1 records in the '20s alone. He was castigated, years later, for being called "the king of jazz," a usurper in the era of the young Armstrong and Ellington, though from many accounts he was a humble man who was embarrassed by the hype. He is one of those figures, like Al Jolson, fated to be inescapable in his own time and a half-memory in subsequent years.

"Wang Wang Blues," the first major Whiteman hit, was recorded on 9 August 1920 and released as Victor 18694-B. On

King of Jazz.

Isham Jones

Isham Jones, another top '20s bandleader, came from Saginaw, Michigan. The son of an Arkansas fiddler, Jones first worked in a coal mine, driving blind mules (and playing a fiddle while he drove them). He crept into show business by degrees, struggling for a decade to make a name as a songwriter, and playing in a few Chicago dance bands, where he learned saxophone to get gigs.

By 1920, Jones and his Rainbo Orchestra (so-called because they played at the Rainbo Gardens on North Clark Street) had become one of Chicago's top jazz bands. Jones' biggest hits were watered-down "society" jazz records (though he wrote some jazz standards, like "It Had to Be You"), but as Allen Lowe has pointed out, the first edition of Jones' Orchestra (1920-21, or basically, the recordings he made before his first #1 hit, "Wabash Blues") had a "sense of swinging musical inevitability informed by a true sense of jazz and its possibilities."

Jones' popularity waned during the Depression, a dip worsened by his ill-considered decision to switch record labels. In 1935 Jones hired a young clarinet player named Woody Herman for a Decca session, and, retiring a few years later, he bequeathed his band to Herman, a final donation to posterity.

Two of Jones' best tracks, "When Shadows Fall I Hear You Calling" and "Wait'll You See," were recorded in Chicago on 1 June 1920, and were released as Brunswick 5018; unavailable on CD at present.

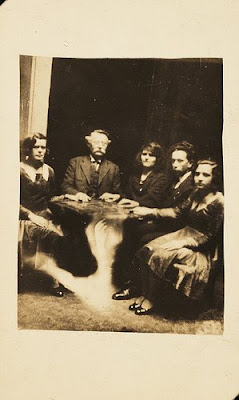

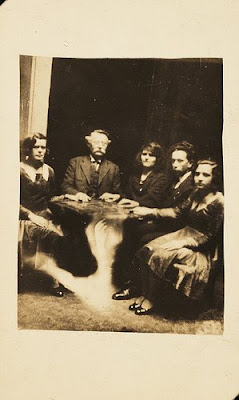

William Hope, Seance, ca. 1920 (National Media Museum).Alquist: Sterility, Helena, is man's last achievement.Helena: Oh, Alquist, tell me why, why?Alquist: You think I know?Helena: (quietly) Why have women stopped having children?Alquist: Because there's no need for them. Because we've entered into paradise. Do you understand what I mean?Helena: No.Alquist: Because there's no need for anyone to work, no need for pain. No-one needs to do anything, anything at all except enjoy himself. This paradise, it's just a curse! (jumping up) Helena, there's nothing more terrible than giving everyone Heaven on Earth!

William Hope, Seance, ca. 1920 (National Media Museum).Alquist: Sterility, Helena, is man's last achievement.Helena: Oh, Alquist, tell me why, why?Alquist: You think I know?Helena: (quietly) Why have women stopped having children?Alquist: Because there's no need for them. Because we've entered into paradise. Do you understand what I mean?Helena: No.Alquist: Because there's no need for anyone to work, no need for pain. No-one needs to do anything, anything at all except enjoy himself. This paradise, it's just a curse! (jumping up) Helena, there's nothing more terrible than giving everyone Heaven on Earth! Karel Čapek,

R.U.R. (Rossum's Universal Robots).

Another version of paradise (coarser, but more lively) can be found in Frank Crumit's "

My Little Bimbo Down on the Bamboo Isle." (This is one of the earliest public appearances of the word "bimbo," which initially was not sex-specific.)

Grosz, Republican Automatons.

Grosz, Republican Automatons.Two American artists, abroad and at home:

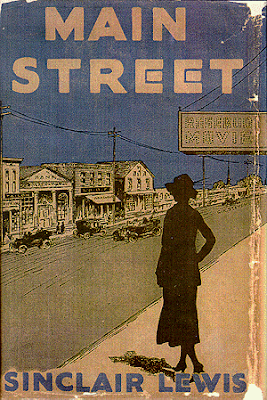

Ezra Pound's "

Hugh Selwyn Mauberley," published in 1920, begins as a scathing autobiographical poem, in which Pound castigates himself and his earlier works ("

For three years, out of key with his time/He strove to resuscitate the dead art/Of poetry"), and then spins outward, cursing the world, which is nothing but a vale of philistinism ("

a tawdry cheapness/shall reign throughout our days") and, foretelling Pound's later obsessions, of "

usury age-old and age-thick." It is a world of cheap plaster reproductions and tinny distractions (pianolas, among other things), with the recent war having burned up the last of the crop:

There died a myriad

And of the best, among them,

For an old bitch gone in the teeth,

For a botched civilization.

This is an abridged version, read by Pound in Washington, DC, in 1958. On

Poetry on Record. More Pound recordings (including a 1939 rendition of "Mauberley")

here.

Charles Ives' publication of his Piano Sonata No. 2 ("Concord Mass. 1840-1860") in the same year marked a quiet coming-out party for Ives, who had spent much of his life as an insurance agent while writing and endlessly revising his silent music, compositions that existed only as private, incomplete scores that were hardly, if ever, performed.

Ives suffered a heart attack at age 44, in 1918; it seems to have convinced him at last to start finalizing and publishing his compositions. During his convalescence, he wrote out the complete "Concord" Sonata as well as his

Essays Before a Sonata, which were basically Ives' program notes for his work.

Each of the Sonata's four movements are Ives' tribute to a particular New England transcendentalist--Emerson, Thoreau, Hawthorne and, in the third movement featured here, Amos and Louisa May Alcott. Ives, in his

essay , describes the teacher Amos Alcott as "

frequently whip[ping] himself when the scholars misbehaved, to show that the Divine Teacher-God was pained when his children of the earth were bad" while his daughter Louisa May, the author of

Little Women, "

leaves memory-word-pictures of healthy, New England childhood days,--pictures which are turned to with affection by middle-aged children,--pictures, that bear a sentiment, a leaven, that middle-aged America needs nowadays more than we care to admit."

Ives, throughout the Sonata, samples the most well-known motif in classical music--the first few notes of Beethoven's Fifth--encasing it, along with excerpts from hymns like "Jesus, Lover of My Soul," in what he called "the human faith melody." As Geoffrey Block wrote, Ives' use of Beethoven is both a tribute and a toppling ("

Ives intended not only to praise Caesar but bury him in an avalanche of new sounds").

As with most of Ives' works, he composed the Second Sonata over decades (in this case, roughly 1904 to 1915, and he kept revising it after its publication) and it wasn't performed until years after its completion. The first documented performance on record was by Katherine Heyman, in Paris in 1928, on a radio broadcast from the Sorbonne. The version of the Sonata's third movement included here is performed by

Pierre-Laurent Aimard.

Next:

Normalcy