Wendell Hall, It Ain't Gonna Rain No Mo'.

Belle Baker with the Virginians, Jubilee Blues.

I.J. Hochman & the Jewish Orchestra, Rusishe Sher (Russian Sher).

Fiddlin' John Carson, The Old Hen Cackled and the Rooster's Gonna Crow.

Piron's New Orleans Orchestra, West Indies Blues.

Darius Milhaud, La Création du Monde: Premier Tableau.

Jesse Crump, Mr. Crump Rag.

Q. Roscoe Snowden, Misery Blues.

Ollie Powers' Harmony Syncopators, Play That Thing.

Thomas Morris Past Jazz Masters, Original Charleston Strut.

The Georgians, Snakes Hips.

Hitch's Happy Harmonists, Cruel Woman.

Charlie Straight's Rendezvous Orchestra, Henpecked Blues.

Jean Sibelius, Symphony No. 6 in D Minor: allegro molto moderato.

Once the band starts, everybody starts swaying from one side of the street to the other, especially those who drop in and follow the ones who have been to the funeral. These people are known as "the second line" and they may be anyone passing along the street who wants to hear the music. The spirit hits them and they follow.

Louis Armstrong, quoted in Ishmael Reed's Mumbo Jumbo.

"It Ain't Gonna Rain No Mo'," Wendell Hall's two-million-seller of 1923, is arguably a rock & roll record, at least in spirit. It's got the whole bag: yodels, howls, whines and sneers, riffs, death, puns, general nonsense, bad attitudes, jokes about animals, jokes about sewers, barefoot girls. Everybody from Bob Dylan on down has stolen from it:

Saw a sign in a hardware store:

"Boy wanted, 16 years,"

Now that's too long to wait for a boy,

It brings eyes to my tears

Hall was a red-headed ukulele player from Kansas. He was a song plugger, a vaudeville rambler, a radio man (even got married on the air). "It Ain't Gonna Rain No Mo'" was the first national radio hit, mainly because Hall traveled cross-country in the summer of 1923, playing at over 35 radio stations, touting his record and his sheet music. To plug the latter, Hall, brilliantly and shamelessly, would keep adding verses to the song (reaching 100 at one point) and then reprint the sheet music with his new lines--in this way, he sold over 10 million copies (& many of the verses were wholly plundered from "traditional" folk songs, often by black musicians). He died in 1969, having never come close to that success again. Then again, few could have.

Initially recorded ca. spring 1923; there were several versions cut that year, with varying lyrics, released as Gennett 5271, Edison 51261, and Victor 19171. Hall cut sequel discs in 1924 and 1933. One 1923 cut is in this archive.

Alice Reighly, president of the Anti-Flirt Club, 27 February 1923 (Shorpy). Fourth rule of Anti-Flirt Club: "Don't go out with men you don't know--they may be married, and you may be in for a hair-pulling match."

Bella Becker was born in New York City in 1893: she was singing on the street by the time she was eight and working in a dress factory by age nine (her exact contemporaries were the girls killed in the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire). She escaped to the stage, changed her name to Belle Baker, and became a vaudeville star, to the point where she could call up Irving Berlin and complain that there wasn't "a Belle Baker song" in a new revue (so Berlin drummed up "Blue Skies" for her to debut).

"Jubilee Blues," which Baker cut with the Virginians, is a stage number that swings about as well as the "official" blues being recorded by the likes of Mamie Smith. The Virginians were a spin-off of the Paul Whiteman Orchestra run by Ross Gorman. Recorded 27 August 1923 and released as Victor 19135-B; on Tin Pan Alley Blues.

And I.J. Hochman's Jewish Orchestra offer a version of the "Russian Sher" on disc. A sher is a "scissors dance," basically a type of square dance popular among Eastern European and Russian Jews in the 19th and early 20th Centuries. As with much early klezmer, the melody is carried by fiddle and clarinet, bass by tuba, rhythm by trombones. It's the Yiddish blues, straight from the shetl. This was one of Hochman's rare instrumental cuts--he was mainly an accompanist to singers like Jenny Goldstein. Recorded in December 1922 and released as OKeh 14059 c/w "Kamenetzer Bulgar."(On Klezmer 1910-1942.)

Harold Lloyd, social climber

Fiddlin' is like salvation--free and without price.

Attributed to Fiddlin' John Carson.

Fiddlin' John Carson, born in Fannin County, Georgia, three years after the Civil War ended, was a wildcat fiddler, a one-man song and dance band, a storyteller, a professional hayseed, "a defiler of tradition" (Allen Lowe) who kept 19th Century music alive. He was one of the first professional "hillbilly" musicians to record. A track from his first session, "The Old Hen Cackled and the Rooster's Gonna Crow," is a fine example of his sound--both archaic, with the music broken up by Carson's barn dance calls, and modern (the occasional dissonance when he plays "double stops," holding down two strings at once).

You may recall this story: In 1913, a 14-year-old girl named Mary Phagan was killed at her workplace, an Atlanta pencil factory. Her supervisor, a Northern Jewish man named Leo Frank, was convicted of the murder, mainly due to testimony by janitor Jim Conley (who likely was the real killer--he had been found washing stains off his shirt and he had given a series of contradictory statements). Georgia Gov. John Slaton eventually commuted Frank's death sentence.

So Fiddlin' John Carson wrote "The Ballad of Little Mary Phagan," a story of a poor girl murdered by cruel Leo Frank. He sang it at every Frank-related protest rally in a 30-mile radius of Marietta, which were many. After Frank's sentence was commuted, Carson changed the lyric to suggest that a "New York bank" had paid Gov. Slaton off.

One August day in 1915, an armed mob hauled Frank out of prison, drove him 175 miles to Marietta and lynched him. "For audacity and efficiency, it was unparalleled in southern history," C. Vann Woodward later wrote of the Frank lynching. All the day long, while Frank's corpse hung from an oak tree, Carson stood in front of the Marietta courthouse, playing his "Little Mary Phagan" over and over again, while the assembled crowd "cheered and applauded him lustily," according to a contemporary newspaper account.

Carson cut records throughout the '20s and died a happy old man in 1949.

Recorded in Atlanta ca. 14 June 1923 and released as OKeh 4890 c/w "The Little Old Log Cabin in the Lane."

"Take from the dresser of deal,/Lacking the three glass knobs, that sheet/On which she embroidered fantails once/And spread it so as to cover her face"

Armand Piron was Clarence Williams' business partner and a musician in his own right--a violin player, bandleader, songwriter (he composed "I Wish I Could Shimmy Like My Sister Kate" although Louis Armstrong later complained that he'd been ripped off).

Piron thought "West Indies Blues" by Spencer and Clarence Williams and Edgar Dowell, was a sure-seller, and so recorded three versions of it over a few weeks: this one was cut on 21 December 1923 and released as Columbia 14007-D; on Archive of American Popular Music.

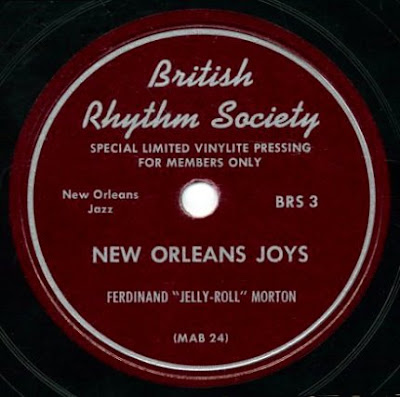

Opening day, Yankees Stadium, April 1923.

The composer Darius Milhaud, visiting the United States for the first time in early 1923, became entranced by jazz, which he heard straight from the source: the Capitol Palace in Harlem, where James P. Johnson, Willie "the Lion" Smith and the young Duke Ellington were playing nightly. (He may have heard Bessie Smith sing as well, as she was in town during his visit and Milhaud describes having heard "a Negress whose grating voice seemed to come from the depths of the centuries.") Milhaud was already convinced that "animated rhythms," in his words, would be the future of music, and in 1919 had composed a ballet about Carnival filled with Brazilian-influenced rhythms.

Now Milhaud tried to incorporate jazz stylings into classical ballet, arranging an orchestra of what he hoped would be 18 soloists, including a double-bass and a brass section of alto saxophone, trombone, trumpet and French horn. La Création du Monde, in which impressionist jazz serves as the soundtrack to the world's formation, had a scenario, by the poet Blaise Cendrars, allegedly derived from African folklore, which means, in part, having dancers depict "trees uprooting themselves and impregnating the ground with their fruit."

Here's the first tableau (there are five in all, along with an overture), "the chaos before creation," which opens with a violin soloing over a throbbing beat that's very reminiscent of Rite of Spring. When clarinet and trumpet slide in soon afterward, it sounds a bit like an early draft of "Rhapsody in Blue."

La Création du Monde debuted in Paris on 25 October 1923 with "African" sets by Léger. This recording is conducted by Kent Nagano and performed by the Orchestre de l'Opera de Lyon.

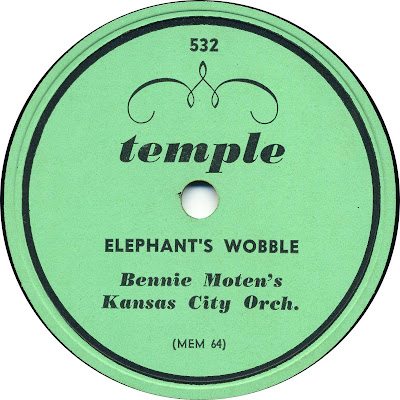

Warren C. Huddleston interviewed the pianist Jesse Crump in the fall of 1951, when Crump was still making a living playing around the country. At the time he was in Muncie, Indiana, about to head out to San Francisco. Huddleston tracked down Crump at home, and played him some of his oldest records, including the solo track "Mr. Crump Rag." Crump listened, his eyes closed. "That tune goes a long ways back," he said. In 1923, Crump had been playing at the Golden West Cafe in Indianapolis, and soon afterward he'd meet Ida Cox, who he married, and Jelly Roll Morton, who he rivaled.

Crump once mentioned he was billed as "The Man Who Plays With a Thousand Bands," which meant he accompanied a jukebox. Huddleston went out to see Crump play in Muncie that night. What he heard was pure American music:

[Crump] was playing solo piano at a local spot...blues, boogie, hillbilly, bop. All the request stuff. The bar was next to the railroad yards, and Jesse's piano was forced to compete with switch engines and the constant clash of shuttling freight cars.

"Mr. Crump Rag" was cut on 20 July 1923 but was only released at the time by Gennett as a private pressing; on the awkwardly-titled Male Blues of the '20s.

Who was the mysterious Q. Roscoe Snowden? A black pianist who recorded in the early '20s, mainly as an accompanist for blues singers, he made a pair of solo tracks in 1923 that show a well-developed sense of swing.

"Misery Blues" was recorded in New York in October 1923 and released c/w "Deep Sea Blues" as OKeh 8119; on Piano Blues Vol. 4.

Calvin Coolidge meets the press

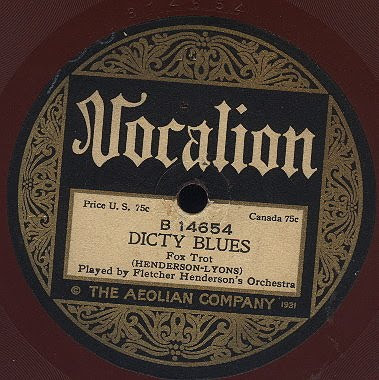

Testaments of five lost dance bands:

Ollie Powers, a mysterious figure who may have been a drummer in Chicago, formed something of a knock-off version of King Oliver's band in 1923. But for a knock-off, it was made of pretty quality material including the cornetist Tommy Ladnier and the clarnetist Jimmie Noone (and briefly Louis Armstrong, en route to New York).

"Play That Thing," a hot stomping track, was recorded in September 1923 and released as Puritan 11263/Claxtonola 40263 (Puritan was a Paramount subsidiary, Claxtonola a short-lived Iowa City label that mainly reissued Paramount and Gennett discs). On Chicago Rhythm-Apex Blues.

The cornetist Thomas Morris had been playing jazz in New York since the early '10s, and by the mid-'20s was something of a linchpin of the New York scene, playing with Fats Waller and Mamie Smith, among others. Morris' playing is often used as an example of "classic" early jazz trumpet before the emergence of Louis Armstrong. Morris eventually gave up music, first working as a redcap in Grand Central Station and later joining Father Divine's Universal Peace Mission Movement, changing his name to Brother Pierre and considering the aforementioned Father to be the second coming of Christ. When Sidney Bechet saw him on the street, Morris introduced himself as "St. Peter," much to Bechet's amusement.

The sparkling "Original Charleston Strut," which is enough divinity for me, was cut in February 1923 and released as OKeh 8055 c/w "E Flat Blues No. 2"; on Thomas Morris 1923-1927.

The Georgians were another Paul Whiteman Orchestra spin-off, led by the violinist Paul Specht and dominated by the trumpeter Frank Guarente. "Snakes Hips" was recorded 15 March 1923 and released as Columbia A3864 c/w "Farewell Blues"; on Jazz in Britain.

Gance, La Roue.

Hitch's Happy Harmonists, led by Curtis Hitch, were an early jazz territory band, mainly covering southern Indiana: emblematic of the sort of new "white" jazz brewing up in Indiana during the '20s, they played with Hoagy Carmichael (who recorded "Washboard Blues" with them) and fell entirely under the spell of Bix Beiderbecke's Wolverines, to the point where some Harmonists records sound interchangeable with Wolverines ones.

Their "Cruel Woman" was cut in Richmond, Indiana, on 19 September 1923 and released as Gennett 5286 c/w "Home Brew Blues."

And Charlie Straight, a journeyman Midwestern pianist and bandleader, had formed a nine-man outfit in 1923 that seemed dedicated to pushing ragtime conventions into freer jazz forms. Straight's orchestra at this time was Lee Riley (c), Holmes Coltman (tb), Al Kvale (cl,as), Ray Puttnam (cl,ts), Julian Davidson (bjo), George Hookham (bb), Don Morgan (d). The swinging "Henpecked Blues" was recorded in Chicago in June 1923 and released as Paramount 20244; on Chicago Rhythm.

Brancusi, Bird In Space.

As he no doubt would have preferred, Jean Sibelius seems utterly removed from any other musician or composer in this collection. Born in Finland in 1865, he would become both the soul and the embodiment of an independent Finland, to the point where an image of Sibelius' head was printed on the hundred-markka note (before Finland converted to the euro). He began much in the way of other "nationalist" composers of the late 19th Century like Bartok--digging through national myths and folk songs and composing tone poems. By 1910, much of his efforts had turned to writing symphonies, a form he once described as "a confession of faith at different stages of one's life."

The sixth symphony always reminds me of the scent of the first snow.

Jean Sibelius, 1943.

The Sixth Symphony in D Minor is a bit neglected compared with titanic works like Sibelius' Fourth and Fifth, but its wintry beauty is astonishing. Here's the first movement, which begins with oboe and flute quietly responding to a gorgeous phrase on strings (much of the opening is in the Dorian mode, aligning the work with the mode often used by folk musicians and, in the words of Alex Ross, "with antique modes underpinning the harmony, it's as if the composer were trying to flee into a mythic past").

The symphony was debuted in Helsinki on 19 February 1923; this recording was conducted by Herbert von Karajan and the Berliner Philharmoniker.

Next: New People

Lately in Bowieland: karma, curry, pixiephones, Pancho.