Irma Thomas, We Won't Be In Your Way Anymore.

Carole King, It's Too Late.

Lynn Anderson, Rose Garden.

Loretta Lynn, One's On The Way.

Jean Knight, Mr. Big Stuff.

Vicki Anderson, I'm Too Tough For Mr. Big Stuff (Hot Pants).

Honey Cone, Want Ads.

Merry Clayton, Southern Man.

Ruth Copeland, Play With Fire.

Joni Mitchell, Little Green.

Betty Wright, Clean Up Woman.

Bonnie Raitt, Women Be Wise.

Shirley Bassey, Diamonds Are Forever.

Mary Lou Williams, What's Your Story, Morning Glory?

The Joy of Cooking, Brownsville/Mockingbird.

Esther Phillips, I'm Getting 'Long Alright.

In New York, in the summer of 1971, most of her friends have gone out of town. So Diane Arbus stays in her tiny apartment with its view of the Hudson (one envied by her neighbors). She haunts the Walker Evans exhibit at the Museum of Modern Art, goes to movies in the afternoon. A former classmate sees Arbus slumped in a seat at the 68th Street Playhouse, but the classmate, depressed herself, avoids talking to her.

Arbus has already established her name (MoMA has bought some of her photos) but her finances are a mess. She spent the past spring sparring with Harper's over an expenses claim. She picks up a few assignments--fashion shows, Tricia Nixon's wedding, a black separatist minster in Detroit, Hortense Calisher's latest author photo (Calisher has the shots destroyed). Arbus has, as she has for decades, found her art in photographing her menagerie of freaks: the misshapen, the distorted, those who hate their bodies, those who bear them like scarred trophies. Eddie Carmel, the "Jewish giant" of the Bronx, or a New Jersey housewife who makes her pet macaque wear a baby's bonnet and snowsuit, or an albino sword-swallower. The latter is the subject of one of Arbus' last photographs--she stands before a carnival tent, her arms outstretched, the sword half down her throat. The sword's hilt and the swallower's body each make a crucifix.

"Lately it's been striking me how I really love what I can't see in a photograph," Arbus tells her students in what will be the last photography class she teaches. She lingers on "the element of actual physical darkness...it's very thrilling to see darkness again."

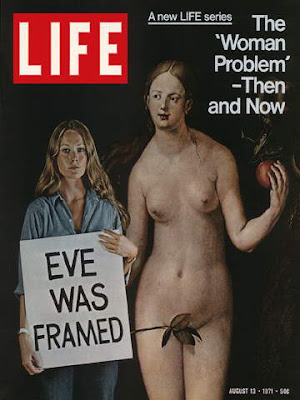

In 1971 the radio is full of women. They ring across every narrow band, with songs of reckonings and negotiations. A marriage ends early one morning, cloud-strained daylight falling across the kitchen table. Another ends late one night with a call from a phone booth. In Irma Thomas' "We Won't Be In Your Way Anymore," we never hear Thomas' husband as he surveys his empty home--maybe he's stunned, or screaming. Thomas just dissects the marriage (disclosing she's been beaten in the last verse), tells him where his wallet and keys are, lets him know the kids will be all right now. "You done me wrong, you done us wrong," she sings at the fadeout. Those are her final words to him: her phone call lasts only as long as the record. (Two Phases of Irma Thomas)

Carole King's "It's Too Late," played everywhere that summer, answers "One Fine Day," which King co-wrote when she was 21. The wedding photos are in boxes in the closet, the only conversations left are vague reminiscences about when they first met. Old friends' names come up as punchlines to forgotten jokes. The woman wakes one morning and knows she can't play her part anymore, though she tries to cushion the blow. King's piano chords slam close each verse, and finally the song. It's a wintry contrast to the ebullient piano line with which King had opened the Chiffons' track: innocence at last bows to experience. (Tapestry).

Pat Nixon at work in the White House, ca. 1971

In early 1971 Lynn Anderson's "Rose Garden" tops the pop and country charts; its rhinestone arrangement and dancing melody make it fit for a Nixon White House social. Yet its lyric is blunt as it is wise, sung by a wife standing her ground, brokering her humanity. As with other songs hanging in the air that year, it can be ground down to a single line: It doesn't have to be this way; it won't be this way any longer.(16 Greatest Hits.)

Gloria Steinem, interviewing Pat Nixon on the campaign plane during the '68 election, had asked Nixon who her greatest influences had been when she was growing up. Who had she identified with?

Pat Nixon, born in a Nevada mining town, had lost her mother to cancer and her father to silicosis before she was 18. She had made it through the Depression taking any job she could find--as a cashier, an X-ray tech, sweeping floors in a bank. She and her husband had clawed out of the hole with their fingernails; she had endured the humiliation of having her husband beg for his VP slot on national television, and she would endure worse in August 1974, smiling while her husband boarded a helicopter home to California. So Pat Nixon looked at Steinem, took her measure, drew a breath. "I never had time to dream about being someone else," she said. "I had to work."

Loretta Lynn's "One's On the Way" is on All Time Greatest Hits.

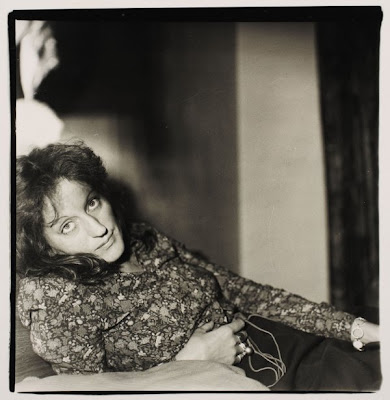

New Woman magazine hires Arbus to shoot Germaine Greer, who has recently helped to pummel Norman Mailer in a debate over feminism. Greer opens the door of her Chelsea Hotel room to see "a rosepetal-soft delicate girl" struggling with her camera equipment. Greer, six feet tall and imperious, has sympathy. Yet once she's set up, Arbus commands Greer to lie flat upon her hotel bed, and nearly slams her wide-angle lens into Greer's face. She baits Greer, asks intrusive, personal questions, snaps the shutter whenever Greer tenses or snaps out an answer. So Greer makes her face a mask. "It was tyranny. Really tyranny," Greer later told Patricia Bosworth. "But because [Arbus] was a woman I didn't tell her to fuck off. If she'd been a man, I'd have kicked her in the balls." The session's a failure: New Woman rejects the photos.

Also in the Chelsea Hotel while Arbus wars with Greer: Harry Smith, in Room 705, playing Skip James 78s for a visiting monk; Dennis Hopper and Terry Southern, stumbling out onto 23rd Street convinced that it's Sunday; Patti Smith, a scrawny kid hanging out in the lobby. Radios and hi-fis, their voices barely muffled by the walls, carry the news: the swagger-beat of Jean Knight's "Mr. Big Stuff"; its muddy, impenetrable answer record by Vicki Anderson; the modern girl group hit "Want Ads," where the singers, hardened by betrayal, saunter back into the market (the line "going to the evening news" sounds like "going to the interviews," a finer, colder phrase, with sex becoming just another job) (Soulful Sugar).

Merry Clayton, born in Louisiana, makes Neil Young's "Southern Man" a damnation, singing the three syllables of "suh-thern-MAN" like three downward thrusts of a knife. Ruth Copeland turns the Stones' "Play With Fire" on its head. The original has Mick Jagger in his typical '60s role, a rake taunting a slumming upper-class girl. Now Copeland's working-class girl, her family still back in the coal mines, slowly rips her would-be seducer to bloody tatters. (Invictus Sessions.)

It was the height of the suicide years. Mark Rothko in 1970, John Berryman hurling himself off the Washington Avenue Bridge in 1972, Anne Sexton sitting in her garage two years later. Shelley Broaday, a photographer who lived in Arbus' building, leaped off the roof in spring 1971. Pills and drink, the neighbors said. The kids living down the hall from Arbus begin writing songs about suicides--they had already known a few.

The songs keep coming, filling the spaces. Joni Mitchell, mourning a child she gave up for adoption, imagining the life she would have no hand in forming, asserts that "you're sad and you're sorry but you're not ashamed." (Blue). Shirley Bassey, in the theme song of a dreadful new James Bond film, casts her lot with money (Diamonds Are Forever OST). Betty Wright rues that she neglected her man enough to let another woman poach him (I Love The Way You Love); Bonnie Raitt, reviving a Sippie Wallace blues (Raitt used Wallace as her lodestar in those years), offers hard wisdom while she readies to pounce (s/t).

Sometime--morning, late at night--on 26 July 1971, Diane Arbus lies down, clothed, in her bathtub after taking an overdose of barbiturates, and slashes her wrists. Up on the roof, the kids are listening to the Apollo 15 launch. Arbus has two daughters. She is forty-eight. Her journal's last entry, on 7/26: "The Last Supper." The last person to have seen her alive was Walter Silver, who saw her on the street carrying a flag. There's a persistent rumor that Arbus had set her camera up to shoot her in the tub.

Only a few people went to Arbus' funeral in early August. Most of her friends were away for the summer, and they didn't hear the news until they came back to the city. Richard Avedon, an old friend, did make it, and he was heard saying he wished he could've been an artist like her. And his old friend Frederick Eberstradt allegedly whispered back: "No you don't."

It shouldn't end there. End it with jubilation, whether in Mary Lou Williams reviving "What's the Story Morning Glory?"(Nite Life), or the Berkeley-based collective The Joy of Cooking. "Goin' to Brownsville/gonna take that right-hand road," hymn Toni Brown and Terri Garthwaite. Or end it with resilience, with Esther Phillips' "I'm Getting 'Long Alright" (Confessin' the Blues).

Top: Diane Arbus, "Germaine Greer, Feminist In Her Hotel Room," 1971.

Many details taken from Howard Sounes' Seventies and especially Patricia Bosworth's Diane Arbus: A Biography.