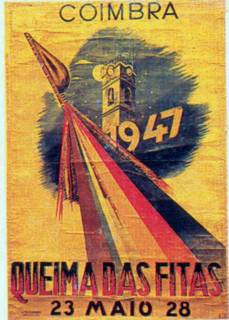

1947

"A little bit of what made the preacher dance"

Charlie Parker, Relaxin' at Camarillo.

"A little bit of what made the preacher dance"

Charlie Parker, Relaxin' at Camarillo.

Charlie Parker, Embraceable You (take 1).

Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie, A Night in Tunisia.

A parliament of Bird.

On Saturday evenings, in the latter months of 1946, the patients of Camarillo State Hospital gathered to hear the house band. The orderlies are setting up folding chairs in rows of half-circles, a few nurses are talking quietly over coffee in the back of the room. The band drifts together, setting up, chattering. The hospital's name is stitched on all of their clothes.

On the slightly raised stage, holding a C melody saxophone, is a new inmate, who you might have seen tending a plot of lettuce in the garden. He tells the drummer how much he is enjoying bricklaying, saying he could have been a mason. And when the music starts, the Thorazine-silenced schizophrenics, those patients still twitching from electroshock, those blinking because they've been stuffed in a cell all week, the nurses and the janitors hear Charlie Parker play.

Parker had been committed to Camarillo after being arrested for walking around a Los Angeles hotel lobby naked and, later the same night, allegedly setting his room on fire. He had deteriorated in the summer of '46--some say from bad-quality drugs, others from increasing music pressures. But his six months at Camarillo, which was not a soothing restorative place by any account, seemed to settle Parker, realigned him, so when he returned to music in February 1947, he was ready for his year of miracles.

Throughout '47, Parker recorded a score of fluent and brilliant performances, notching one masterwork after another on the acetates. His sound had changed subtly--it was no longer just his flashing strings of notes, his sharp, driving tone. He was quieter, moodier. He had never been far away from the blues, even in his wildest flights--now it was calling him back.

"

Relaxin' at Camarillo," a tribute to his happy prison, is a pretty democratic recording, with Parker sharing solo time generously with most of his bandmates. Parker comes first on alto sax, jumping around warily; Wardell Gray's tenor, by contrast, is smooth, with all questions answered.

Recorded in Hollywood on February 26, with Howard McGhee (t), Dodo Marmarosa (p), Barney Kessel (g), Red Callender (b) and the Woody Herman band's Don Lamond (d).

More on

Camarillo, which was shut down in 1997.

Parker soon returned to the East Coast, where he assembled a new band with many of his regulars, including Miles Davis and Max Roach. And, nine months after he was playing in a psychiatric ward, Bird played Carnegie Hall on September 29, where he reunited with his "worthy constituent" Dizzy Gillespie. It would be a rare night: Gillespie and Parker, who had made the founding documents of bebop together, would come together only a handful of times in the late '40s and '50s.

"

A Night in Tunisia" was one of the great bebop records of '45, but here, freed from the tyranny of the three-minute 78 rpm limit, Parker can let loose. After the opening theme is finished, the first four bars of Parker's solo is a proud, stupefying explosion of notes--the audience hails him like a champion. Then it just gets better; bits of "KoKo" turn up amidst the diamonds. Gillespie keeps up in his turn, soaring like a hawk. With John Lewis (p), Al McKibbon (b) and Joe Harris (d).

Then there is "

Embraceable You." This is Parker at his most sublime, his most beautiful. There are two incredible takes--this is the first, lesser known take, in which Parker barely acknowledges the Gershwin theme, tearing off into his own musings. The opening six-note motif of his solo doesn't come from Gershwin--Gary Giddins pegs it as from "A Table in the Corner," a cheap '30s pop song, demonstrating Parker's alchemical skills.

Recorded October 28, with Davis (t), Duke Jordan (p), Tommy Potter (b) and Roach (d).

"Camarillo," and one take of "Embraceable" can be found on this

phenomenal set. "Tunisia" is found

here.

We wrap up 1947 at last, and so:

Favorite Films of '47, dedicated to the

East Bay Express.

Out of the Past. Fulfills every promise

film noir ever made. Here the past is a malevolent force, levying its due from the present. Bob Mitchum is iconic, Jane Greer phenomenal--part of the film's plot parallels her real-life attempt to escape the grasp of Howard Hughes.

Black Narcissus. Desperate, beautiful nuns steam in hothouse convent in India. The Archers come close to campiness but do not fall over--the next year, in

The Red Shoes, they did.

The Late George Apley. A death letter for Brahmin Boston.

Quai des Orfèvres.

Ramrod. Veronica Lake gets revenge. Director André de Toth, who once awoke to find himself laid out in a morgue, courted the fabulous

Lake by offering her a knife "to cut out his unworthy Hungarian heart." She married him.

The Senator Was Indiscreet. Political hack rises to Senator, and aims for President, through blackmail.

Ginrei No Hate.

The Ghost and Mrs. Muir. The only good man is a dead one.

Les Maudits. All submarine films are locked-room mysteries; one of the finest.

Road to Rio. The end of the road for Crosby and Hope. Ahead lay televised mediocrity and golf tournaments.

Curios:

Lady in the Lake./

Dark Passage. Both have the same "first-person" gimmick--the camera eye is the lead character's, though"Lady" is more rigorous in its dedication than is "Passage," which gives up after 20 minutes. The concept bombs because it means lots of awkwardly framed shots in which the lead looks into mirrors, or endless stretches of another character talking directly into the camera. Later revived for stalker horror films.

New Orleans: Billie Holiday is reduced to playing a maid, a role that incensed her, and the story is too lame to justify calling the film truly good, but the jazz talent on screen is astonishing--Woody Herman, Louis Armstrong, Kid Ory, Barney Bigard, Zutty Singleton etc.

Happy New Year. See you next week in 2005, or 1948, whichever you would prefer.