1952 Rosemary Clooney, Don’t Worry ‘Bout Me.

Rosemary Clooney, Don’t Worry ‘Bout Me.

Kay Starr, Wheel of Fortune.Popular music of the early 1950s, if it is considered at all today, is remembered mainly as a foil for rock and roll; described in turns as dreary, confectionery, cloying and irritating, pop hits of the early fifties have long been sloughed off into oblivion, returning only once in a while in muzak garb on "easy listening" radio stations or whistled by a grandmother in the kitchen.

Certainly, a good deal of it was dreck: Carleton Carpenter & Debbie Reynolds singing “Aba Daba Honeymoon”; Reynolds’ future husband Eddie Fisher inflicting a host of wretched songs upon the airwaves, like “Lady Of Spain”; Patti Page’s “How Much is that Doggie in the Window”, which has become over the years the embodiment of the insipid type of music rock & roll allegedly destroyed.

Yet there was something else to these songs besides their grandiose melodies-- a shared sense of melancholy, a taste for desperate escapism, sometimes undercut by a sort of domestic stoicism. In great part these were songs for women, often performed by women, and whenever such songs are prominent, the period gets written off by (mostly male) writers of future generations as being weak, sappy and requiring rock & roll demolition. The same critical revision happened to the early '60s, when the girl groups ran the show (i.e., rock & roll had "died" and needed resuscitation by the Beatles); it likely is underway right now with regards to the late 1990s, when the charts were dominated by boy bands and former Mouseketeers, crafting songs for teenage girls, diluting and mocking the High Painful Seriousness of the grunge era.

In his marvelous book

Sonata for Jukebox, Geoffrey O’Brien describes what it was like to be a child in the '50s hearing these songs, and what they meant to the older women in his house:

“

Ruth undertakes her meticulous work of arranging and folding and dusting accompanied by Perry Como and the McGuire Sisters and the Mills Brothers arranging and folding sound, as if to keep the whole enterprise moving forward. It seems that the music has been made for her and if whenever one song happens to suit her even better than the rest of them it’s an occasion for gratitude: a song like that is a token of mutual assistance… Love and Marriage, Cry Me a River, Sentimental Journey, Three Coins in the Fountain, Rags to Riches, Music Music Music: these are pieces of an unending cycle of story poems, an opera without boundaries or fixed roles that has been unfolding since before I was born and will keep playing until I figure out what they are singing about… Now and then an isolated phrase stands out. The turning of Kay Starr’s “Wheel of Fortune” mesmerizes even while its function remains unknown.”

Starr's "Wheel of Fortune" is still mesmerizing, especially the spooky, revolving harmonies in the chorus ("

spinning, spinning, SPIN-ning"). Find it

here.

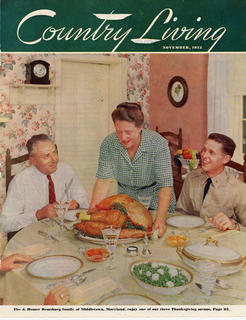

The audience for this music was not a typical one-–these were women who had come of age, as my grandmother did, at the height of the Depression, who had spent their prime years during the war, working, fearing for their boyfriends, husbands and brothers, sometimes losing them. It was a generation deprived of its youth, in the postwar sense of the word--whatever carefree moments you had, you earned.

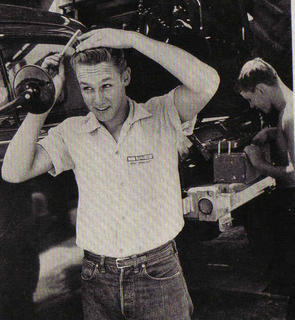

Rosemary Clooney, having grown up during the war, was now off on her own, still keeping the faith although the guy she was waiting for proved to be a waste. "Don't Worry 'Bout Me", a breakup song of amazing grace, humanity and wistfulness, documents resilience in the face of disappointment, provides a cheerful delusion (the singer graciously tells her lover move on to another woman) to cover the loss. Clooney sings the first bars of each verse with strength but then lets the rest of the phrase taper off--she's regretted her words as soon as she's sung them. Found on

Everything's Rosie, an odds-and-ends '50s compilation.

By 1952, the great travails were over, the men had returned (even Korea, the miserable coda to WWII, was winding down), the children were coming--for many of these women, their prayers during the hard years had been answered. All that was left now was to grow old--happily for many, dismally for some--while the songs would be always there to remind them of all they had lost. And then, one day, the songs would go too.

(for HBM, 1914-2001.)

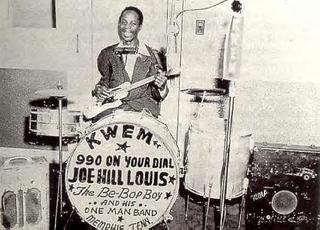

Willie Mabon, I Don’t Know.In the

1952 presidential election, the Republicans retook the White House after two decades of losses, thanks to their choice of Gen.

Eisenhower over someone who better represented the soul of the party, the conservative Sen. Taft. (As a sop to the right, Ike chose for his running mate an

ambitious Congressman who had cut his teeth red-baiting.) Eisenhower, the sort of ideologically blank candidate that turns up on rare days to the great benefit of his party and occasionally of his country, was the last (to date) of the lineage of great American generals who devolved into mediocre presidents. That said, Eisenhower ran the country like a genial corporate chairman: he mainly left FDR/Truman reforms alone; he pushed to build the interstates and backed up

Brown v. Board of Education with federal troops. He was honest, not vindictive and knew a snake (McCarthy, Nixon) when he saw one; he ranks in the top tier of 20th Century presidents, if elevated more by his competitors than by his actions.

He crushed

Adlai Stevenson, first in the long line of Democratic presidential candidates considered by voters to be essentially too qualified for the job.

Harry Truman went home to Missouri, hated by a great many of the American public, who, in later, darker years, would remember him with much more fondness (one great aunt of mine told me once, in the '80s, "You know, President Truman wasn't as stupid as he made out to be.")

I think Willie Mabon would have voted for Stevenson. On the

Chess Blues-Rock Songbook. Films of 1952Lo Sceicco Bianco (The White Sheik)

Films of 1952Lo Sceicco Bianco (The White Sheik). Others may favor Fellini’s extravagant later epics like

8 1/2 but for me his masterpieces are his first two films, this and '53’s

I Vitelloni, where his baroque taste for fantasy is tempered by the grime of real life. Funny, heartbreaking and marvelously acted.

Le Plaisir. Soon, the complete run of "Three's Company" will be available on DVD, but not any of Max Ophuls' great films.

Plaisir, which starts with one of the most amazing continuous shots ever achieved, is a collection of three vignettes; it achieves perfection with the longest, a story of a group of prostitutes and their madam going on holiday in a small country town.

Singin’ in the Rain. This, along with '53's

The Band Wagon, marks the end of the great Hollywood musicals. I mean, come on, who doesn't like "Good Morning"? Or Donald O'Connor's astonishing "Make 'Em Laugh" (which landed him in the hospital for a week after he did it, and then he had to do a re-take)? Or the title song? It's a Russian nesting doll of a movie--a film about actors remaking and redubbing a film (Debbie Reynolds' dubbing work being in turn dubbed by another singer), in the midst of which Kelly imagines another surreal film sequence (the "Gotta Dance"/Cyd Charisse bit, which almost destroys the movie).

Ikiru/

Umberto D. The timing of these films’ release (just ten months apart) makes one believe coincidence has some divinity to it. Two studies on death and obsolesence; the Kurosawa film offers release, the De Sica despair.

Jeux interdits.

Outcast of the Islands.

Bend of the River/

The Big Sky. Both more satisfying '52 Westerns to me than

High Noon, a film I've never liked.

The Bad and the Beautiful. A Hollywood epitaph that reeks of wormwood; it begins with Kirk Douglas paying extras to show up at his father's funeral.

The Lusty Men. Mitchum. Nicholas Ray. Enough said.

Park Row.Ochazuke no aji (The Flavor of Green Tea Over Rice). Minor Ozu, sure, which is like saying “minor Shakespeare.”

Oddities:

My Son John. I saw a bit of this film years ago, on a terrible quality VHS bootleg. As many have said, it is to anti-Communism what "Reefer Madness" is to marijuana use. Unbelievably bad but marked with an inadevertant gonzo genius, and a sad depiction of Hollywood's paranoia/cowardice in the face of HUAC.