7 Drinks of Mankind: Cola The New Seekers, I'd Like to Buy the World a Coke.

The New Seekers, I'd Like to Buy the World a Coke.

Lord Invader, Pepsi Cola.

Mel Tillis, Coca Cola Cowboy.

The Fugs, Coca Cola Douche.

Lost Kids, Cola Freaks.

Edwin Birdsong, Cola Bottle Baby.

The Clash, Koka Kola.

The Waltons, Coca Cola is Coke.

The Coolies, Coke Light Ice.

T. Rex, Pepsi Jingle.

A Prelude

"We took off our goddam skates and went inside this bar where you can get drinks and watch the skaters in just your stocking feet. As soon as we sat down, old Sally took off her gloves, and I gave her a cigarette. She wasn't looking too happy. The waiter came up, and I ordered a Coke for her--she didn't drink--and a Scotch and soda for myself, but the sonuvabitch wouldn't bring me one, so I had a Coke, too. Then I sort of started lighting matches. I do that quite a lot when I'm in a certain mood. I sort of let them burn down till I can't hold them any more, then I drop them in the ashtray. It's a nervous habit."J.D. Salinger,

The Catcher in the Rye.

Our American CousinHe thought he was the king of America

where they pour Coca Cola just like vintage wine.Elvis Costello, "Brilliant Mistake."

The Sumerians and Egyptians bequeathed us beer, the Greeks, Romans and Hebrews, wine; to the Arabs we owe the miracles of distillation and coffee; the Chinese have given us tea. As for the Americans, we have given the world soda pop.

In particular, we have given the world cola. Call it the taste of modern democracy, the upper that is safe for children to drink, the world's common currency, a symbol of everything enjoyed and reviled about the United States. Providing a happy daily dose of caffeine and sugar to the masses, cola is a completely artificial drink that is advertised as being "real"; it is the great leveler--literally colorless, able to be drunk in the morning or evening, in any season, at any caste of society.

Cola, against the wishes of its manufacturers, also has become a metaphor for progress or imperialism, take your pick. For the Eastern bloc during the Cold War, it was a symbol of the forbidden lures of the West; for the nationalist in Indonesia, or Ghana, or Yemen, it is an acid dissolving centuries of tradition, apparently overnight.

Perhaps there is only one thing everyone can agree on about cola:

it's not good for your teeth.

Andy Warhol, Green Coca Cola Bottles, 1962.

Andy Warhol, Green Coca Cola Bottles, 1962.There are very few cola songs in popular music, in good part because the two major soda companies have done an admirable job over the past century in writing and creating their own approved music, brilliantly aping current sounds, and paying the biggest names in popular music, from Ray Charles to Michael Jackson, to sing for them.

The only "unauthorized" songs about cola tend to be obscure, odd things, half-remembered at best, by bands whose names few have heard. They are funny, bitter, sometimes violent--but almost impossible to summarize, really. Writing about Coke is like writing about the President, or Allstate Insurance--it's almost too broad a target, too ambitious a task to take on in the confines of a song.

Plus, the cola companies and their hired songwriters are strong competition: cola jingles have a way of infesting contemporary music and creating simulacra that sound as good as, if not better than, than the real issue.

Take Michael Jackson's Pepsi ads from the mid-1980s, in which Jackson rewrote his hit "Billie Jean" (for over $5.5 million) as "You're a Whole New Generation." Greil Marcus, in

Lipstick Traces, thought the commercial was a stronger track:

"

...one could hear 'You're a Whole New Generation' as a new piece of music. It was tougher: the rhythm was harsh, the production not elliptical but direct, Jackson's voice not pleading or confused but fierce. When he sang the line, "That choice is up to you", dramatizing the consumer's option of Pepsi vs. Coke, he made it sound like a moral choice."

It's hard to describe just how culturally ominpresent these ads became--I recall reading the TV listings in the newspaper and seeing that an episode of "Love Boat" was highlighted

simply because a Jackson commerical was going to air during the show.

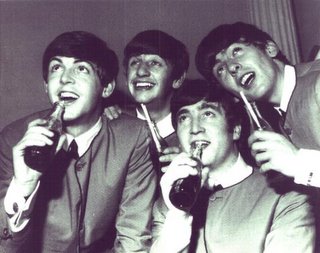

1964: the two Atlantic icons meet at last

1964: the two Atlantic icons meet at lastBut perhaps the greatest case in point is the New Seekers' "

I'd Like to Buy the World a Coke", from 1971, the most memorable of Coke jingles, at least for anyone in my generation, to whom the song became a childhood hymn.

The jingle was so popular that the ad was hastily rewritten into an actual pop hit, "I'd Like to Teach the World to Sing," with lyrics celebrating Coke replaced by Madison Avenue's idea of hippie-isms, but "I'd Like to Buy the World a Coke" sounds far better than its "legitimate" replacement. It's punchier, the harmonies are craftier, and, since it's barely a minute long, it compresses the song into its core essence. If you want, go ahead and buy a CD

full of commercial jingles. "

Remember, just because you get hooked on the jingle for a particular commercial, you are under no obligation to actually go out and buy/use the product," as one helpful Amazon reviewer writes.

Or Lord Invader's happy "Pepsi Cola", which isn't a jingle but sounds like it's auditioning for the role. The song was allegedly the fruit of an attempt by Pepsi to push songwriters to create a rival for the then-popular "Rum and Coca Cola"; Invader's version was never released, and was at last collected on a new compilation:

Calypso in New York. Fixed air

Fixed air"

The whole washed down with generous amounts of Tab, a fiery liquor brewed under license by the Coca-Cola Company which will not divulge the age-old secret recipe no matter how one begs and pleads with them but yearly allows a small quantity to circulate to certain connoisseurs and bibbers whose credentials meet the very rigid requirements of the Cellarmaster. All of this stupendous feed being a mere scherzo before the announcement of the main theme, chilidogs."

Donald Barthelme,

We Have All Misunderstood Billy the Kid.

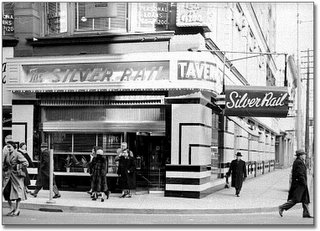

Soda was born around 1767, when an English clergyman and amateur chemist, Joseph Priestley, who lived next door to a brewery, began experimenting with what the brewers called "fixed air": that is, the bubbling gases generated by the fermentation vats. By pouring water between two glasses held over a brewing vat, Priestley was able to cause the gas to dissolve in the water instead, creating "sparkling water."

By 1800, the concept of soda water--water infused with what we now know is carbon dioxide--had diffused throughout Europe, though generally considered a sort of medicine. (Even today, drinking Coke is the best thing for an upset stomach, I find). The likes of Schweppe in London began selling soda water as a general, all purpose beverage, and by 1810, soda water was being sold in the U.S. as well: the soda "fountain" (whose product would be mixed with various syrups, such as strawberries or sarsaparilla) becoming a staple of apothecary shops, the forerunners of drug stores.

Much of this history comes from (of course) Tom Standage's

A History of the World in Six Glasses.

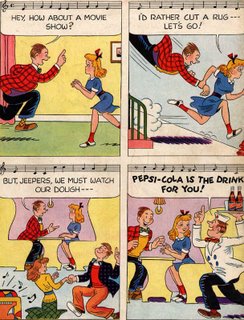

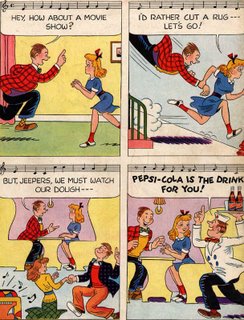

Pepsi graciously provides its own sheet music for its awful cartoon

Pepsi graciously provides its own sheet music for its awful cartoonCola--essentially, soda water infused with extracts from the coca plant and/or kola nuts--came out of this tradition, but also has ties to another venerable American ancestor--the traveling quack.

"I'll be shot if it ain't a Yankee!" begins

Constance Rourke's depiction of a typical traveling hustler, descending upon an American frontier town, circa 1780.

"

With scarcely a halt, the peddler made his way into their houses and silver leapt into his pockets. When his pack was unrolled, calicoes, glittering knives, razors, scissors, cotton caps made a holiday at a fair...every one bought...Staying the night at a tavern, he traded the landlord out of bed and breakfast and left with most of the money in the settlement..."

Throughout the 19th Century, a regular feature of your typical mountebank was his variety of elixirs for sale--balsams, creams, oils, concoctions--a good many of which consisted of adulterated dope: laudanum, cocaine, morphine. And in addition to the traveling quack, there was a strong growth in the "patent medicine" catalog business after the Civil War, in which someone with a toothache could order via mail essentially a nice gallon of dope for her troubles.

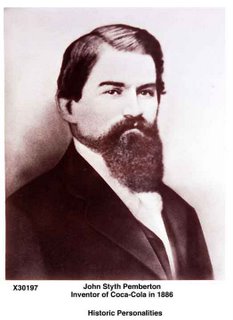

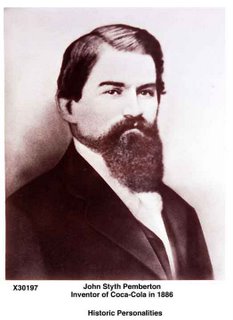

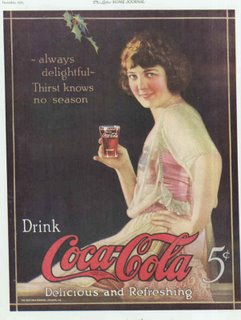

Coke paterfamilias

Coke paterfamiliasAn Atlanta pharmacist named John Pemberton had been reading in medical journals about some of the latest wonder cures, and determined to experiment with a few. One was extract of the coca plant. Leaves of the coca plant, when chewed, provide the sort of natural high similar to that caused by chewing tea leaves or coffee beans, but in 1855, cocaine was extracted for the first time from the leaves, and the world would never be same again.

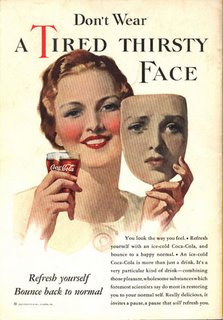

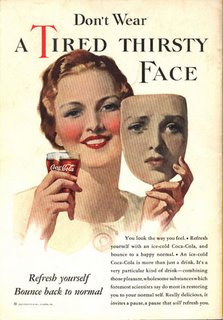

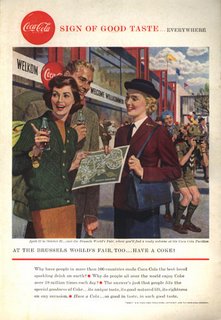

Coke ad,1933: wearing a face that she keeps in a jar by the door

Coke ad,1933: wearing a face that she keeps in a jar by the doorPemberton first attempted to sell a coca-infused wine, to which he added another hip additive--extract of African koka nuts, which had long been used in Western Africa as an all-purpose pain reliever and pick-me-up. In classic grifter fashion, Pemberton essentially stole the formula of a French coca wine and even rewrote celebrity testimonials so that they became endorsements for his own drink.

But Pemberton, whose coca wine likely would have flopped eventually and been filed away in history's dustbin, got a second chance when Atlanta decided to prohibit alcohol sales for a two-year trial period in 1886. Pemberton went back to the laboratory to create a non-alcoholic version of his drink, coming up with soda water infused with coca and kola and a good dose of sugar to mask the bitterness of the two main ingredients. Thus was born Coca Cola, first offered in an Atlanta pharmacy in May 1886.

Pemberton was dead of stomach cancer two years later, and after a legal wrangle, control of Coca Cola fell to

Asa Candler, the man who would transform Coke from a questionable drugstore potion to the lifeblood of American commerce. (Candler always hated the nickname "Coke".)

Two American takes on Coke: "Coca Cola Cowboy", Mel Tillis' contribution to the Clint Eastwood 1978 film

Every Which Way But Loose (the first of the orangutan movies). On

Greatest Hits. A contribution by Jamie at

Radio CRMW.

And The Waltons' "Coca Cola is Coke" was the B-side of the band's

first single, released in 1987. While I was trying to come up with songs that would qualify for this post, I remembered hearing this track many, many years ago or so on a college radio station, but figured I would never find it. But, thanks to coincidence or divine intervention, the fine blog

Something Old Something New posted it earlier this week. So thanks to them.

The monument of Queens, NY

The monument of Queens, NYCoke had its growing pains. In 1898, the federal government began finally regulating patent medicines, which Coke was classified as, and imposed a tax on them. So Candler and other Coke barons had to make a critical choice--whether to give up marketing Coke as a wonder drug (and risk losing the lucrative pharmacy trade) and instead push it as a healthy, family-friendly general beverage. They went with the latter choice, which made them millionaires. (Around 1900 also came the appearance of Coke's great rival, Pepsi.)

The drink had its enemies, such as

Harvey Washington Wiley, the first FDA Commissioner and a leading force behind the 1906 Pure Food and Drug Act. Wiley began investigating Coke soon afterward, worried that children were heartily drinking caffeine and even traces of cocaine in a drink their parents believed to be harmless.

A Cocaine InterludeYes--there was cocaine in Coca Cola, up until 1905 or so. It's one of those things that stoners and the conspiracy-minded love to obsess about, but drinking a bottle of Coke was usually never the equivalent of doing a line of coke--by the time of mass production, ca. 1900, the drink only had very small traces of cocaine (in the form of coca extract) in it.

Some estimate Pemberton's original mixture, however, had about

9 mg of cocaine per glass. So if you had three Cokes a day, well, you're feeling pretty elated. It was enough to give the drink a racy reputation: In William Faulkner's

The Sound and the Fury, written in the late 1920s, Faulkner has the repugnant Jason Compson heading to the drugstore every few hours for a "dope", which Compson claims helps his headaches.

And the parallels between international Coke distribution and international drug cartels proved too potent for some to resist. The Clash's "Koka Kola", from 1979's

London Calling, sums it up--one of the album's lesser tracks, but one I've always enjoyed.

The United States v. Forty Barrels and Twenty Kegs of Coca ColaWiley's case against Coke, the brilliantly-named

The United States v. Forty Barrels and Twenty Kegs of Coca Cola (1911), was Coke's life or death moment. But Wiley, luckily for Coke, blew his prosecution--calling as witnesses religious fundamentalists who blamed Coke for various sexual transgressions ("wild nocturnal freaks" at one girl's school, allegedly) and a number of junk scientists who drew upon shaky experiments involving rabbits. The core problem for Wiley, and what doomed him, was that he appeared to be mainly attacking Coke for having caffeine in it, which was not illegal, and nor was Wiley was not looking to ban tea or coffee, which had similar doses.

The courts ultimately ruled in favor of Coca Cola, which did agree to reduce its caffeine count and not to picture children in its advertisements (something it adhered to until the 1980s). So Coke was finally freed of its unsavory reputation, and prepared to become something far greater than John Pemberton could have ever dreamed.

1918: Coke has done its part, now do yours

1918: Coke has done its part, now do yours"Wild nocturnal freaks" sounds pretty interesting. The Lost Kids were a Danish punk group: "Cola Freaks" is from their only release, a 1979 EP. I found the track last year on the blog

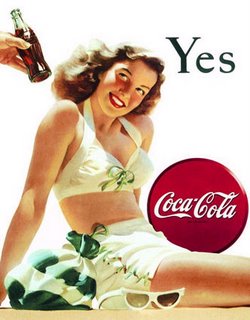

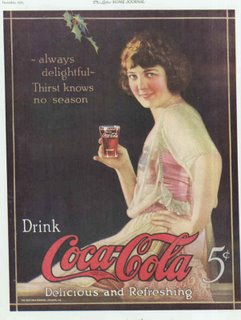

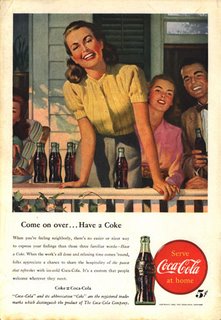

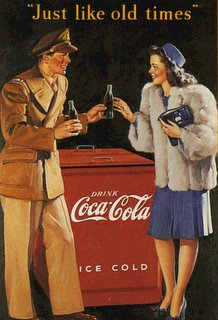

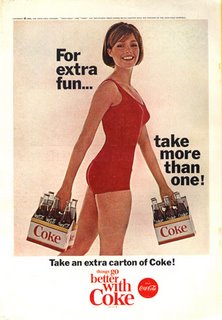

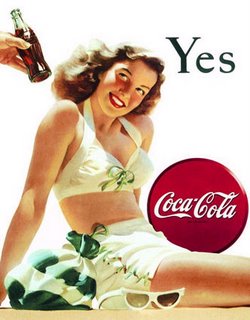

Strange Reaction.Thirst Knows No SeasonThe walls decorated with posters, bathing girls, blondes with big breasts and slender hips and waxen faces, in white bathing suits, and holding a bottle of Coca-Cola and smiling--see what you get with a Coca-Cola?John Steinbeck,

The Grapes of Wrath.

move over, Molly Bloom

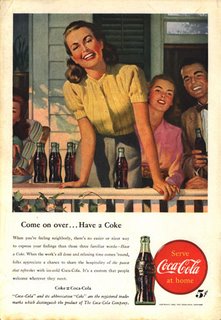

move over, Molly BloomGoing through a bunch of old Coke magazine ads from the '20s through the '60s for this post, what struck me is that a great many of them could have doubled as

Esquire pin-ups. What sold Coke? Apparently pictures of pretty girls, decade after decade.

1923: Prohibition? What prohibition?

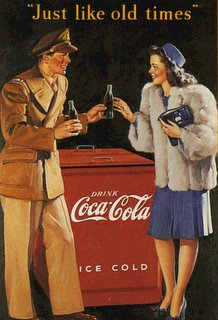

1923: Prohibition? What prohibition?The WWII years were the pinnacle of this strategy. Along with cheap 5-cent Cokes, soldiers in Europe and Asia were plastered with illustration after illustration of beautiful, eager girls waiting for them back home.

1943: fuel for the baby boom

1943: fuel for the baby boom

1947--utterly ecstatic because you're coming home!!

1947--utterly ecstatic because you're coming home!! 1945--just like old times indeed

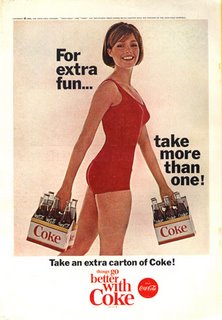

1945--just like old times indeedCola has also had a long, if sadly ineffective, use as an alleged

spermicide by desperate teenagers.

"Back in the 1950s and 1960s, this method of parenthood prevention proved somewhat popular because not only was it cheap and universally available at a time when reliable birth control methods were hard to come by, but it also came in its own handy "shake and shoot" disposable applicator. After intercourse, the girl would uncap a warm Coke, put her thumb over the mouth of the bottle, shake up the beverage..."Read

on if you want the gory details.

1965--the end of the Coke cheesecake era

1965--the end of the Coke cheesecake eraThe Fugs' "Coca Cola Douche" is an ode to teenage Coke-bottle contraception. This is a live recording from the Fillmore East in 1968, found on

Golden Filth. (Studio version on

Virgin Fugs.) Contributed by Jamie from Radio CRMW. A warning for the wary--this is probably the most obscene song ever posted on this site.

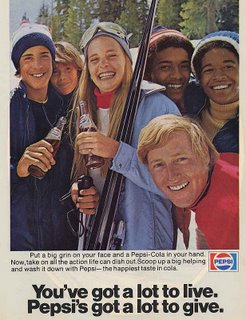

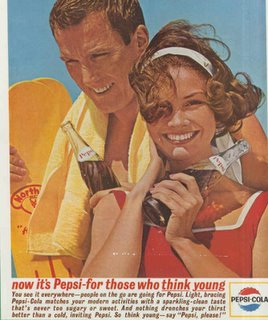

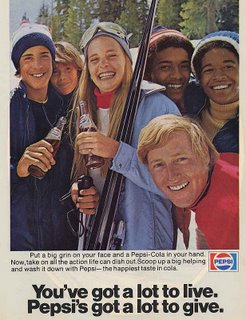

By the early '70s, the era of the Coke Babe ended, replaced by photos of happy young people of mixed sex and mixed races, creating a sort of utopian society of true believers. The lustful urges have been replaced by frenetic activity--that's why people in cola ads are always hand-gliding, or water-skiing, or snowboarding or running down a mountain. Poor bastards.

Edwin Birdsong's 1979 "Cola Bottle Baby" was the template for the Daft Punk track "Harder, Better, Faster, Stronger". Birdsong, a neglected funk artist who's been championed by a number of fine blogs over the past year, deserves a good anthology. Until then, "Cola Bottle" is only available on expensive,

out of print CDs.

In Which Coke and Pepsi Conquer the World"At every table, some great-auntwould steer him with cool spotted handsto a glass of Coca-Cola.One even sang to him, in all the Englishshe could remember, a Coca-Cola jinglefrom the forties. He drank obediently, thoughhe was bored with this potion, familiarfrom soda fountains in Brooklyn."Martin Espada,

Coca Cola and Coco Frio.

Some time between Pearl Harbor and the founding of NATO, Coke and Pepsi began dominating the world.

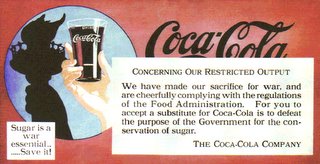

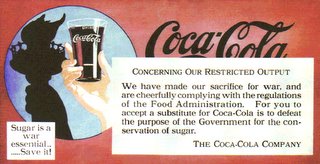

It happened innocently enough--American troops in WWII, being shipped to the South Pacific and Europe, wanted a steady supply of Cokes, and Coke complied, keeping its price at five cents a bottle, regardless of production costs. Of course, this was helped by Coke being exempted from sugar rationing, which the company managed by stressing its morale-boosting efforts.

Rather than shipping Coke overseas, which would have cost a fortune, Coke instead set up military-run production and bottling plants. These followed in the wakes of Allied victories--Northern Africa, Italy, France, the Netherlands, Burma, the Philippines, and ultimately Germany and Japan. When the war ended, the plants stayed, now being run by civilians. Suddenly, Coke had local production units in nearly every Western European country, as well as a good chunk of the Pacific. By 1950, a third of Coke's profits came from outside the U.S.

Group Capt. Lionel Mandrake: Colonel... that Coca-Cola machine. I want you to shoot the lock off it. There may be some change in there.Colonel "Bat" Guano: That's private property.Mandrake: Colonel! Can you possibly imagine what is going to happen to you, your frame, outlook, way of life, and everything, when they learn that you have obstructed a telephone call to the President of the United States? Can you imagine? Shoot it off! Shoot! With a gun! That's what the bullets are for, you twit!Guano: Okay. I'm gonna get your money for ya. But if you don't get the President of the United States on that phone, you know what's gonna happen to you?Mandrake: What?Guano: You're gonna have to answer to the Coca-Cola company. Dr. Strangelove

Group Capt. Lionel Mandrake: Colonel... that Coca-Cola machine. I want you to shoot the lock off it. There may be some change in there.Colonel "Bat" Guano: That's private property.Mandrake: Colonel! Can you possibly imagine what is going to happen to you, your frame, outlook, way of life, and everything, when they learn that you have obstructed a telephone call to the President of the United States? Can you imagine? Shoot it off! Shoot! With a gun! That's what the bullets are for, you twit!Guano: Okay. I'm gonna get your money for ya. But if you don't get the President of the United States on that phone, you know what's gonna happen to you?Mandrake: What?Guano: You're gonna have to answer to the Coca-Cola company. Dr. Strangelove, 1964.

Coke's association with Western policies, becoming a symbol of Yankee aggression and thus banned by the USSR and its satellites, wound up helping Pepsi, which began bottling soda in the USSR during the '60s, for example.

Cildo Meireles, Inserções em Circuitos Ideológicos: Projeto Coca-Cola [Insertions into Ideological Circuits: Coca-Cola Project] 1970

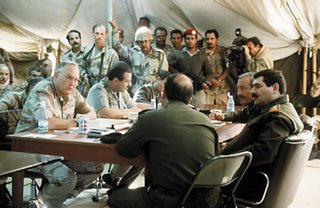

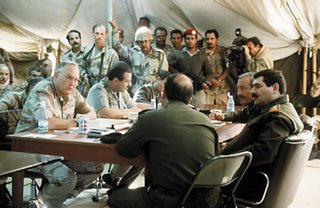

Cildo Meireles, Inserções em Circuitos Ideológicos: Projeto Coca-Cola [Insertions into Ideological Circuits: Coca-Cola Project] 1970And so it on went--Coke getting in trouble in the Middle East, first for allegedly ignoring Israel to win a share of the growing Arab market, then facing an Arab boycott in 1968 for setting up shop in Israel; Pepsi winding up on the table of the Iraqi cease-fire in 1991, and both occasionally getting dumped on the ground, burned in effigy and blamed for all sorts of atrocities, real and cultural, by people around the globe.

1991: Norman Schwarzkopf accepts Iraqi cease-fire, with strategically placed PepsiI said to him, "Why is it, Alfonse, that decent, well-meaning and responsible people find themselves intrigued by catastrophe when they see it in television?"I told him about the recent evening of lava, mud and raging water that the children and I had found so entertaining. "We wanted more, more.""It's natural, it's normal," he said, with a reassuring nod. "It happens to everybody.""Why?""Because we're suffering from brain fade. We need an occasional catastrophe to break up the incessant bombardment of information...Only a catastrophe gets our attention. We want them, we need them, we depend on them. As long as they happen somewhere else. This is where California comes in. Mud slides, brush fires, coastal erosion, earthquakes, mass killings, et cetera. We can relax and enjoy the disasters because in our hearts we feel that California deserves whatever it gets. Californians invented the concept of life-style. This alone warrants their doom."Cotsakis crushed a can of Diet Pepsi and threw it at a garbage pail.

1991: Norman Schwarzkopf accepts Iraqi cease-fire, with strategically placed PepsiI said to him, "Why is it, Alfonse, that decent, well-meaning and responsible people find themselves intrigued by catastrophe when they see it in television?"I told him about the recent evening of lava, mud and raging water that the children and I had found so entertaining. "We wanted more, more.""It's natural, it's normal," he said, with a reassuring nod. "It happens to everybody.""Why?""Because we're suffering from brain fade. We need an occasional catastrophe to break up the incessant bombardment of information...Only a catastrophe gets our attention. We want them, we need them, we depend on them. As long as they happen somewhere else. This is where California comes in. Mud slides, brush fires, coastal erosion, earthquakes, mass killings, et cetera. We can relax and enjoy the disasters because in our hearts we feel that California deserves whatever it gets. Californians invented the concept of life-style. This alone warrants their doom."Cotsakis crushed a can of Diet Pepsi and threw it at a garbage pail.Don DeLillo,

White Noise.

A Whole New Generation

The children of Marx (well, maybe not) and Coca Cola

The children of Marx (well, maybe not) and Coca ColaI had thought cola would always be with us, possibly existing as the last beverage on earth, but there are some signs it's losing its long-held grip on youth (at least in the U.S.) Kids who want a caffeine fix are now going for more hardcore stuff, like Red Bull, and there's now a movement afoot by concerned parents to

ban soda vending machines from schools.

"Coke Light Ice" is off the Coolies' 1988 album

Doug (out of print for ages, buy it for a ridiculous price

here), a parodic rock opera about a skinhead who beats up a transvestite cook and steals his recipes. The Coolies were Atlanta-based--their only other record was

dig?, a collection of Simon & Garfunkel covers.

the great dream, still unfulfilledA Half-Century of Coke AdsThe McGuire Sisters, Be Really Refreshed.

the great dream, still unfulfilledA Half-Century of Coke AdsThe McGuire Sisters, Be Really Refreshed.

The Bee Gees, Things Go Better With Coca Cola.

Petula Clark, Things Go Better With Coca Cola.

It's the Real Thing.

Coke Adds Life.

Aretha Franklin and the Supremes, Look Up America.

Coke Is It.

Joey Diggs, Always Coca Cola.

Life Tastes Good.The McGuire Sisters' "Be Really Refreshed", from 1959, is one of Coke's scarier anthems. A high-treble mantra with a main riff possibly performed on accordion(!!), the jingle mainly consists of two strains, chanted and chanted over again, one of which especially gives me nightmares: "King Size Coke Has More for You! KING SIZE COKE HAS MORE FOR YOU!"

A half-decade later, the British Invasion is soon co-opted by Coke, first in a dippy attempt by the Bee Gees, and then by Petula Clark (given a nickname by the American announcer, who perhaps feared "Petula" was too ungainly a name for U.S. audiences). This track is pretty fun, and is not much different than Clark's actual hits, like "I Know a Place." Listen to how Coke ad men have completely aped the mid-'60s pop sound, with lots of echo, a pseudo-Phil Spector booming chorus, rolling drum fills. Godard should have used it in

Masculin-Féminin.

1969's "It's the Real Thing" is pretty rancid, "plastic America" at its finest. Though made by studio hacks, the jingle conveys the image of being performed by guys with helmet hair in matching mustard-colored turtlenecks, singing this sort of crap at frat parties and corporate affairs.

1974's "Coke Adds Life" attempts to get funky, with a sound that appears to have been derived from listening to some Chicago and Crusaders LPs, unfortunately. The lyrics get a little weird, actually: are they singing about "tropical fish" at the end? And from 1975 finds Aretha and the Supremes, both in career troughs, enlisted to make a Coke ad soulful. Dense and messy, but the studio band provides some good bottom end, at least.

1982's "Coke Is It", strikes me, at least in the beginning of each verse, as being a melodic rip-off of Antonio Jobim's "Waters of March." Am I crazy? It's the '80s now, so the sound is clean and crisp, showing off the synthesizer and drum machine the studio musicians just bought from a high-end store on Coke's expense budget.

"Always Coca Cola", from 1992, in which one Joey Diggs brings Coke into the Clinton era, and God help us, Coke's discovered hip hop. Well, just a touch--there's some weak beats and some "scratching" noises. This is the sort of anti-music that gets blasted at you before a movie starts, or follows you around a shopping mall like a happy vagrant.

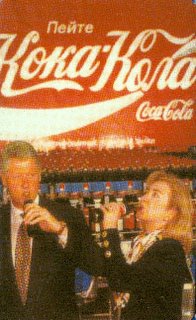

1998: Bill Clinton steels himself for another humiliating round with a slug of Diet Coke

1998: Bill Clinton steels himself for another humiliating round with a slug of Diet CokeAnd 2001's "Life Tastes Good" brings us close to the present day--we've got some ProTooled guitars, a Sheryl Crow soundalike, and a beat designed to serve as the pulse to a rapidly-edited montage of characters from "Laguna Beach" dancing and imbibing Coke.

Pepsi run, Iraq 2004Empty Bottle

Pepsi run, Iraq 2004Empty BottleFirst things--an extra precaution for this post:

Coca-Cola and Coke are registered trademarks of the Coca-Cola company. Pepsi is a registered trademark of Pepsico. This site is in absolutely no way affiliated with either of them, and has no intentions of ever doing so.So, the big question: Coke or Pepsi? For me, there's no choice but Coke. Pepsi to Coke is like Cracked magazine to Mad magazine, Burger King to McDonalds, "Mad About You" to "Seinfeld", Newsweek to Time--there's just something second-place ingrained in the drink. Plus it's too sweet.

Whoof. Almost done. The last entry in this back-breaking series will be an epilogue of sorts, and be much, much shorter than the rest. Look for it early next week.