Andy Goldsworthy splashes a rainbow into being, in Yorkshire no less

The Rolling Stones, She's a Rainbow.

Mandy Patinkin and Bernadette Peters, Color and Light.

Jean Shepard, Color Song (I Lost My Love).

Ice-T, Colors.

Coleman Hawkins, Rainbow Mist.

Paul Simon, Kodachrome.

Julie London, My Coloring Book.

Dolly Parton, Coat of Many Colors.

The Box Tops, Neon Rainbow.

Tony Williams Lifetime, Spectrum.

Boards of Canada, Roygbiv.

Elis Regina and Antonio Carlos Jobim, Chovendo Na Roseira (Double Rainbow).

There are six cardinal colors, and colors have always come to signify more than simply that particular shade, like redneck or got the blues. That's where you apply colors to something else, you know, to come up with what it is you're trying to say. So there are six cardinal colors--red, orange, yellow, green, blue and purple--and there are three thousand shades. And if you take these three thousand shades, and divide them by six, you come up with five hundred. Meaning there are at least five hundred shades of the blues.

Gil Scott-Heron, H2O Blues.

Life, like a dome of many-coloured glass,

Stains the white radiance of Eternity,

Until Death tramples it to fragments.

Percy Bysshe Shelley, Adonais.

The starting point is the study of color and its effects on men.

Wassily Kandinsky, Concerning the Spiritual in Art.

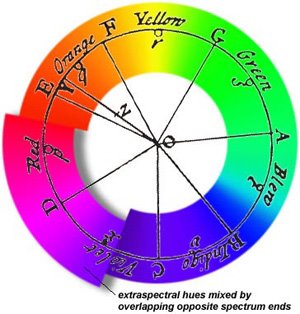

Mr. Newton's color wheel

Welcome to summer holidays. In full color!

A great many souls have tried to entwine color and music. Plato and Aristotle, Isaac Newton, Goethe, Kandinsky: all sought 'natural' links between organized sound and the range of colors. Newton, for example, believed there were seven core colors (creating the strange division between indigo and violet, a subject we'll be returning to later) in great part because he wanted the hues to equal the number of notes in an octave.

It's a logical perception, after all--there do seem to be similarities. We perceive both music and color indirectly, for one thing. We hear a note played on a piano, but our ears only pick up the vibration caused in the air by the struck piano wire; we look at a red rose, but we only see the small band of light that the rose, after having absorbed the rest of the spectrum, has cast back to our eyes.

(So a rose is the rejection of red, a clear sky is the absence of blue, a field of grass the banishment of green. The color of an object is the one color the object discards, as if a family were to be defined by the child they disowned.)

While ev'ry beam new transient colour flings,

Colours that change whene'er they wave their wings.

Alexander Pope, The Rape of the Lock.

The sound of color

The colors that depend on simple ratios, like the concords in music, are regarded as the most attractive, for example halourgon [purple] and phoinikoun [red] and a few others like them..

Aristotle, On Sense and the Sensible.

Many Greek theorists believed color to be a sort of adjunct to music--Plato's friend Archytas of Tarentum helped introduce the "chromatic" musical scale, crafted in part to chart the parallels between pitches and colors. Like sound, color could be measured, graphed--its changes predicted in definable steps. The chromatic scale was meant to reflect color's mutability--compared with older scales, like the diatonic, the chromatic scale featured tones closer in range. It was considered more nuanced ("domestic," sneered Ptolmey, adding that he feared it could turn men into cowards), and harder to play.

Centuries passed, Classical Greece faded into legend and the Roman Empire rose and fell into decadence: all the while "colorful" music became more and more suspicious. The early Christian philosophers picked up on Ptolmey's dislike of the chromatic scale, considering such harmonies to be lewd and frivolous. Essentially, the more 'colorful' the music, the more grotesque and libertine it was.

"...the pliant [chromatic] scales are to be driven as far as possible from our robust minds. These through their sinuous strains instruct one in weakness and lead to ribaldry...Chromatic harmonies, then, are to be abandoned to immodest revels and to florid and meretricious music."

Clement of Alexandria, Paedagogus: How to Conduct Ourselves at Feasts.

The Empire fell and the music of the ancients tumbled into obscurity. Medieval scholars, puzzled as to what the fuss about 'chromatic' music was all about, slowly began to revive the idea that color and music were natural counterparts.

God gave Noah the rainbow sign--in the Vienna Genesis, 6th Century, only green and red are to be found.

It was Isaac Newton, in the late 17th Century, who established a unified theory of color and light, built upon discoveries about optics from the likes of Johannes Kepler. And Newton applied his theories to the musical scale. So it began: the next two centuries would see endless attempts by craftsmen, musicians and cranks to use this knowledge to create "color organs", essentially transmitters of colored light that could be played like a harpsichord or piano.

There was the French Jesuit Louis-Bertrand Castel, who spent his life trying to devise an "ocular harpsichord," capable of playing 144 "nuances" of color, a working model of which was likely never constructed. Or D.D. Jameson, who in 1844 produced a pamphlet detailing a sort of colored piano keyboard ("it activated shutters in front of a dozen flasks of colored liquids arranged in prismatic order. Lamps were to shine through bottles into a darkened tin-lined room." (from John Gage, whose Color and Culture is the source of much of this information.)

Color is just as capable as music of providing us with the highest ecstasies and delights.

Morgan Russell, 1913.

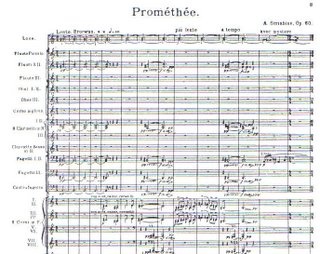

Perhaps the noontide of "color music" came in the late 19th Century and early 20th C, when composers like Alexander Scriabin (who believed each major color had a counterpart key) included passages for color organs and other such devices in their works. For Scriabin's Op. 60, Prometheus: Poem of Fire, the first instrument listed is the color organ "luce" (see below):

Scriabin had intended the Prometheus, while performed, to be accompanied by colored lights flooding the auditorium, with dancers mimicking the light changes. When the symphony premiered in Moscow, in 1911, that wasn't quite the case--there was apparently only a sort of 'color keyboard' that malfunctioned. A New York performance in 1915 had an actual working color organ, specially made by General Electric. Critics were mixed--some thought the color show to be beautiful, others thought it had no relevance to the music, with colors changing rapidly while the performance was static, or not doing much at all while the music reached a crescendo.

Scriabin pressed on, working on his masterwork, to be called Mysterium, a seven-day rite that would include more colored lights and also, in an apparent attempt to further expand the audience's senses, controlled odors. He graciously died before completing it.

Throughout the rest of the century, as Gage writes, "color music was an art form which was always about to become the most important 20th century art, but never quite became it."

True, there were some artists who achieved a sort of color-music fusion: Mary Hallock Greenewalt, who said color music was an art "that can play at will on the spinal marrow of the human being", and who patented a console in 1927 that featured a "moonlight" key. Or Thomas Wilfred, designer of the Art Institute of Light, composer of works like the Lumia Suite (which played, almost completely unattended, in the basement of the Museum of Modern Art in the early 1960s), or the two-day-long Vertical Sequence No. II.

But sadly, the most successful type of color music performance these days are those laser-light shows set to Pink Floyd, which planetariums offer as a public service to stoners.

The blues are still blue?

Despite the decline in fashion for avant-garde color-music, the links between the visual and the aural persevere in popular music, across genres and time. When a song is named after a certain color, does the mind perceive it differently? Do the blues really have a sound? Are there instruments that have yellow tones, are "red" songs truly rageful and intense, is there a strand of music so decadent and precious it deserves to be called purple?

Sometimes a song's color is merely a question of the songwriter finding an easy rhyme. For instance, in the realm of English, a language comparatively impoverished in rhyme, "blue" is an heiress, and a promiscuous one at that--the happy fact that it mates easily with "you", "true", "do", etc., has made it ubiquitous in romantic songs. Hence the thousands of "blue" songs. (By contrast, blue's miserly sister, orange, has no rhymes at all.)

So let's enjoy the spectrum.

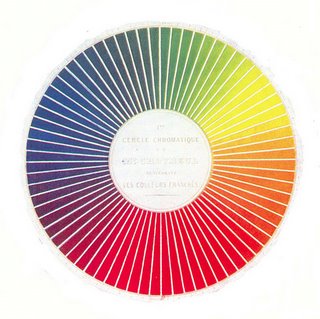

Michel-Eugene Chevreul, color wheel, 1864.

He is all fault who hath no fault at all:

For who loves me must have a touch of earth;

The low sun makes the colour: I am yours.

Alfred, Lord Tennyson, Idylls of the King.

The difficulties of presenting marriage are inordinate. Its forms are at once so varied, yet so constant, providing a kaleidoscope, the colours of which are always changing, always the same.

Anthony Powell, Casanova's Chinese Restaurant.

Our opening palette

Colors win you over more and more. A certain blue enters your soul. A certain red has an effect on your blood pressure. A certain color tones you up. It's the concentration of timbres. A new era is opening.

Henri Matisse, 1952.

Did the Rolling Stones ever record a prettier song than "She's a Rainbow"? With Nicky Hopkins on music box piano and featuring some of Jagger's most vivid lyrics ("her face is like a sail"). While a year before the Stones had released the definitive misogynist record, the summer of 1967 worked its alchemy even on Jagger and Richards, who found themselves at the altar of a Technicolor fertility goddess. On the goofy, ominous Their Satanic Majesties Request from late 1967. This is the mono version, for those who care about such things.

"And you, sir. Your hat so black. So black to you, perhaps. So red to me."

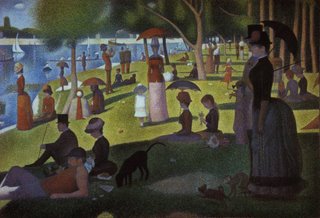

"Color and Light" is from Stephen Sondheim's Sunday in the Park With George, from 1984. The only Broadway musical to date made about Georges Seurat. Original cast recording, with Mandy Patinkin as Seurat and the ageless Bernadette Peters as Dot, is out of print, but can be found here. Lyrics here.

"Color Song" is from 1960, a florid (literally) murder ballad by the inimitable Jean Shepard. On the out of print but essential Honky Tonk Heroine.

Ice-T's "Colors" is from Dennis Hopper's 1988 film of the same name--the colors referred to, of course, are the blue and red colors of the Crips and Bloods gangs, respectively. Before he became a staple of "Law and Order", before he became a political kicking ball due to his "Cop Killer" song, Ice-T simply delivered the news. Freedom of Speech, from 1989, is probably his best record; "Colors" is on The Evidence.

"Rainbow Mist": You likely know of Coleman Hawkins' "Body and Soul" from 1939, a song-length improvisation that defined the tenor saxophone, but you might not be aware that Hawkins recorded a sequel to it (using the same changes as "Body and Soul") in 1944, which, if less definitive, could be more beautiful than its predecessor. On Delmark's Rainbow Mist.

"Kodachrome" is Paul Simon's perfect AM hit from 1973. Sadly, they are indeed taking his Kodachrome away, and quickly: Kodachrome 25, the finest color slide film ever manufactured, was discontinued in 2002, Kodachrome Super 8 is no longer made either, and Kodak has gutted production of the remaining brands, 64 and 200. Only three labs in the world still process it (Dwayne's Photo Service, of Parsons, Kansas, is the last place in America.) On There Goes Rhymin' Simon.

Kander and Ebb's "My Coloring Book" was best known in a version by Kitty Kallen in 1964--this, Julie London's near-contemporary take, is a bit more restrained and moodier. On End of the World (paired with the brilliantly-titled Nice Girls Don't Stay For Breakfast.)

"Coat of Many Colors," from 1971, is one of Dolly Parton's sweetest performances. Young Dolly took flak for her coat, but didn't have as rough a time as Joseph did with his. On Essential.

"Neon Rainbow," in which the Box Tops get mildly psychedelic, is from 1967. On Soul Deep.

The Tony Williams Lifetime was one of the best attempts to fuse acid rock and jazz at the end of the '60s, though Williams didn't quite match what his mentor, Miles Davis, was doing on that front. On John McLaughlin's "Spectrum", however, Lifetime is pure relentlessness, hitting groove after groove, thanks to Williams and organist Larry Young; McLaughlin's guitar work is the stuff of legend. On 1969's Emergency (now out of print?).

The Boards of Canada's "Roygbiv" is from 1998's Music Has the Right to Children.

double rainbow, Portland, OR.

And end with Elis Regina and Tom Jobim. Not speaking a word of Portuguese, I have no idea if "Chovendo Na Roseira" actually does translate into "Double Rainbow", but the composition, one of Jobim's most delicate melodies, certainly sounds lustrous. On 1974's Elis and Tom.

Next:

See, your guests approach:

Address yourself to entertain them sprightly,

And let's be red with mirth.

No comments:

Post a Comment