Lloyd Stalcup, Stuttering Song.

Edward Meeker, Stuttering Dick (and His Stuttering Sweetheart).

Billy Murray, K-K-K-Katy.

LMP (La Musique Populaire), K-K-K-Katy.

Arthur Fields, Oh Helen!

The Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem, The Stuttering Lovers.

Billy Jones and Ernest Hare, You Tell Her, I Stutter.

Frank Guarente's Georgians, You Tell Her, I Stutter.

The Cotton Pickers, You Tell Her, I Stutter.

Jimmy Lee Prow, You Tell Her, I Stutter.

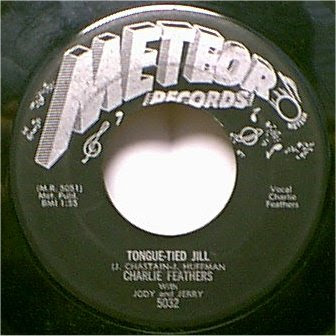

Charlie Feathers, Tongue-Tied Jill.

The Five Scamps, Stuttering Blues.

John Lee Hooker, Stuttering Blues.

Ian Whitcomb, N-N-Nervous.

The Who, My Generation.

Patti Smith Group, My Generation.

Morris Minor and the Majors, Stutter Rap.

Lord Brigo, Stuttering Mopsy.

Joe, Stutter.

Living Stereo, Stammer.

It must've been around then (maybe that same afternoon) that my stammer took on the appearance of a hangman. Pike lips, broken nose, rhino cheeks, red eyes 'cause he never sleeps. I imagine him in the baby room at Preston Hospital playing eeny, meeny, miney, mo. I imagine him tapping my koochy lips, murmuring down at me, Mine. But it's his hands, not his face, that I really feel him by. His snaky fingers that sink inside my tongue and squeeze my windpipe so nothing'll work.

Words beginning with N have always been one of Hangman's favorites. When I was nine I dreaded people asking me, "How old are you?" In the end I'd hold up nine fingers like I was being dead witty but I know the other person'd be thinking, Why didn't he just tell me, the twat? Hangman used to like Y-words too, but lately he's eased off those and has moved on to S-words. This is bad news. Look at any dictionary and see which section's the thickest: it's S. Twenty million words begin with N or S. Apart from the Russians starting a nuclear war, my biggest fear is if Hangman gets interested in J-words, 'cause then I won't even be able to say my own name. I'd have to change my name by deed poll, but Dad'd never let me.

David Mitchell, Black Swan Green.

A new technology enables our baser impulses. The printing press quickly rolls out invective, slander and celebrity gossip; the photograph, the motion picture and the Internet are soon put to pornographic ends; the telephone, right after the first models are installed in someone's office, is used to harass a woman or to sell something. So it was that just after the dawn of recorded sound came a wave of pop records ridiculing stutterers.

[Note: We're going to head up to the attic and rummage through some horrific old keepsakes, so brace yourself for some wildly offensive music by today's standards. I believe that to deny the past in all its ugliness does no one any good, but neither do I get a kick of out mocking people with speech impediments, so I apologize in advance should anyone take offense.]

The endurance of the stuttering song is greatly due to its timeless appeal to songwriters. Say you're a jobbing hack, trying to get something into the Ziegfeld Follies or, a half-century later, trying to land a song with a Nashville producer. Your material's not much, and you've got to compete with the hundreds just like you.

Then it hits you--write a stuttering song! You've got an instant hook, as the chorus will be an easy-to-remember stutter ("Muh-Muh-Muh-Mazie!" "Chuh-Chuh-Chuh-Changes!") that also serves to pad out a weak line, and you have a ready-made audience of cruel children. (A 14-year-old migrant worker named Lloyd Stalcup, recorded his own brief a cappella stuttering song in August 1940, at Shafter FSA Camp near Bakersfield, Calif.--it was collected as part of the Voices of the Dust Bowl project).

They go too far in their commandments...who enjoin stutterers, stammerers and mafflers to sing.

Plutarch, Morals.

The stuttering song is an heir of the English/Irish/Scottish ballad tradition (Caliban, in The Tempest, at one point seems to sing with a stammer-- "'Ban, 'ban, CaCaliban/has a new master, get a new man"), as there are variations found throughout the 17th and 18th Centuries in the U.K. (e.g., "Goody Groaner: The Celebrated Stammering Glee") .

By the rise of vaudeville, the stuttering song was established enough that it was considered its own small genre, a specialty for comic singers -- "Sammy Stammers," from 1894, is a typical example. These stuttering songs fit naturally into a coarse period whose popular music mocked the Irish ("Bedelia: An Irish Coon Song Serenade"), Jews ("Cohen Owes Me Ninety-Seven Dollars"), Asians ("Chinatown My Chinatown") and blacks (mercy, far too many to mention).

I peeped through the curtain, and saw a very-much-begrimed mill-hand, sitting in solitary state, waiting for the performance to begin. By eight o'clock the audience numbered, in all, about twenty roughs. They hissed nothing--they applauded nothing. They were solemnly apathetic until I came on to sing a stuttering song, called 'Sammy Stammers.'...An argument with our manager ensued, and through the now rapidly-emptying hall, a harsh voice was heard to exclaim, "Fancy paying to 'ear a chap as can't sing wi'out stutterin'!"

Albert Chevalier, A Record By Himself (1895).

Many of the first published stuttering songs were also racist minstrel tunes, like 1898's "He Won't Come Back No Never (A Syncopated Stutter)" or 1899's "Stuttering Jasper." And the earliest recorded stuttering song I could find is Edward Meeker's "Stuttering Dick (and His Stuttering Sweetheart)" from 1908, whose stuttering, slobbering title character is, sadly and unsurprisingly, a "great big tongue-tied coon." The song was written by one Clifford Werner, with the sheet music "fraternally dedicated to the Orange Lodge of Elks 135 Minstrel Co."

One verse in "Dick" captures the stuttering song's typical blend of sympathy and sadism:

It's not right to make fun of him,

For he is not to blame.

You'll kill yourself a-laughin'

When he tries to tell his name.

Even by the time of "Stuttering Dick," the basic scenario for the stuttering song is already in place. The poor stuttering protagonist falls in love but his impediment makes it hard for him to express his feelings. There are typically two outcomes. There is the (relatively) optimistic: in "Stuttering Dick," as in "The Stuttering Lovers," an Irish folk song, the stuttering guy finds a stuttering girl, and the two live in bliss. (This version of "Stuttering Lovers" was recorded by the Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem in 1961).

Then in a nobler, sweeter song,

I’ll sing Thy power to save,

When this poor lisping, stammering tongue

lies silent in the grave.

William Cowper, "There Is a Fountain Filled With Blood."

Then there is the more popular and more tragic scenario, when the stuttering character falls in love, can't communicate his feelings, and winds up scorned and ridiculed. Take the most popular stuttering song of the First World War, Geoffrey O'Hara's "K-K-K-Katy," which was first published in March 1918. The spoken section at the end of Billy Murray's recording, when Katy visits Jimmy on parade and watches as stuttering Jimmy is mocked by everyone else in his battalion, is staggering in its cruelty.

O'Hara, a songwriter who had been hired by the federal government to research and record the music of dwindling Native American tribes, joined the U.S. War Department Commission in 1917, writing songs for soldiers to sing. Eventually he moved to the port of Newport News and traveled from ship to ship to teach sailors the latest tunes.

"K-K-K-Katy," which O'Hara wrote for the war effort, marks the formal perfection of the stuttering song hook, as the chorus has a triplet accompany nearly every stuttered word (click to enlarge):

"K-K-K-Katy" was a colossal hit--more than a million copies of the sheet music were sold, and Murray's record, Victor 18455, was also a smash. Sequels abounded, like "The Daughter of K-K-K-Katy Loves a Nephew of Uncle Sam". (LMP's version from seventy years later (complete with Michael Jackson samples) has a sequel verse in which Jimmy goes off to France, dies in the trenches and comes back as a stuttering ghost, haunting Katy's front gate forevermore.)

And Mel Blanc, as Porky Pig, offered a version of "K-K-K-Katy" in the '50s which was like the meeting of negative and positive matter--stuttering Porky deliberately stuttering the song's lyric, until the chorus begs him to shut up.

The success of "K-K-K-Katy" also spawned a number of dire imitators, including "M-M-M-Mazie" and "Lil-Lil-Lillian" and Arthur Fields' "Oh Helen!" from 1919, which at least has a semblance of a fresh melody. The joke about the singer not-quite-singing "Oh hell" or "oh damn" is well-worn shtick from the era (e.g., the 1905 Edison short film The Whole Dam Family and the Dam Dog.)

"Oh Helen," written by McCarron-Morgan, was recorded in New York on 2 January 1919 and released as Edison 3713. Billy Murray was on the four-part chorus, along with Charles Hart and Steve Porter.

"You Tell Her, I Stutter" is the great transitional stuttering song: while its origins lie in crude vaudeville pop, it extends through the hot jazz era into early rock & roll, and it still exists today as a wordless ghost tune, tootled by ice cream trucks and carnival rides.

The song, written by Billy Rose and Cliff Friend, integrates the stuttered lines into the melody of the chorus and verses, so that while the stuttered words remain the hook, they work with the melody rather than derailing it for cheap laughs. That said, the first recorded version, Edison 51079 by "The Happiness Boys" Billy Jones and Ernest Hare, features a long, stupid joke in the middle that stops the track cold.

The Georgians, 1924

Soon, however, the jazzmen got a hold of it. Two groups recorded "You Tell Her, I Stutter" within days of each other in February 1923. The Georgians, led by Italian-born trumpeter Frank Guarente, were one of the first American jazz bands to regularly tour Europe--their fairly uninspired version of "Stutter" was released as Columbia A3857. On 1922-23.

The Cotton Pickers were the rival Brunswick record label's studio band, or, more accurately, "Cotton Pickers" was a generic name assigned to any studio group. However, this version of the Pickers included the legendary Miff Mole on trombone, who adds some vigor and swing to their recording, making it the best of the lot. Released as Brunswick 2404-A (Billy Jones sings the chorus);on That Devilin' Tune Vol. 1, or buy the actual 78 here for $10!

And Victor Records quickly rushed out its own edition--another version of "You Tell Her, I Stutter" was recorded a month later by Whitey Kaufman's Original Pennsylvania Serenaders, and can be heard here.

Thirty years later, "You Tell Her, I Stutter" resurfaced as a rockabilly song, cut by Jimmy Lee Prow in 1956 for King Records. (I could find no record of a catalog number, so maybe it was never actually released--thanks to Alex Abramovich for this one).

Ironically, in the same year, "Stutter"'s lyricist Billy Rose spoke before the Anti-Trust Subcommittee of the House Judiciary Committee to lament the dire state of popular music. "Not only are most of the BMI songs junk, but in many cases they are obscene junk pretty much on the level with the dirty comic magazines [Rose was testifying as part of an investigation into the song publisher BMI]...It is the current climate on radio and TV which makes Elvis Presley and his animal posturings possible."

Mind, this is the man who once wrote the lines:

"Eep-ipe gimme a piece of pipe!"

Does she kiss you in the parlor?

Oh when she does I sneeze and holler

my tu--tu-tongue and tu-tu-tonsils seem to touch.

And Charlie Feathers' "Tongue-Tied Jill" alters the formula a bit, with Charlie courting a girl who, more than stammering, seems to be speaking in tongues. In a sign of the slightly changing times, Sam Phillips thought the track was too offensive and wanted nothing to do with it, so Feathers shopped it across town to Meteor Records.

Released as Meteor 5022 (recorded on April Fool's Day, 1956); on Get With It.

John Updike: "Stuttering is kind of --I suppose it shows basic fright. Like in the comic strips, when people begin to stutter it's because they're afraid. And also, a feeling that -- my father thought that I had too many words to get out all at once. So, I didn't speak very pleasingly, but I never stopped speaking or trying to communicate this way, and I think the stuttering has gotten better over the years. I have found having a microphone is a great help, because you don't have to force your voice out of your throat, just a little noise will work. But, it was real enough -- you know, you write because you don't talk very well, and maybe one of the reasons that I was determined to write was that I wasn't an orator, unlike my mother and my grandfather, who both spoke beautifully and spoke all the time. Maybe I grew up with too many voices around me, as a matter of fact."

There are few stuttering songs recorded by black musicians, reflecting perhaps the genre's early days in the more appalling extremes of minstrelsy, or simply that given stuttering songs were generally Scots-Irish in origin, they were considered more country material than blues.

In the postwar years, however, stuttering songs began cropping up in blues and R&B. The Five Scamps' "Stuttering Blues," from 1951, is a rebuke to the stuttering song tradition--here, the singer's stutter isn't shackled to the chorus as a singalong hook, but is delivered quietly, almost naturally, in the verses, adding a sense of poignancy to the performance.

The Scamps met at a Civilian Conservation Corps camp in the late '30s and began recording just after the war ended, playing in Kansas City and California until the mid-'50s. On The OKeh R&B Story.

And John Lee Hooker's "Stuttering Blues," recorded in 1953, is a revelation--a song whose singer isn't a poor victim but a player, wooing a girl through his stammer. On the LP Don't Turn Me From Your Door.

Claudius: "I limp with my tongue and stutter with my leg! Nature never quite finished me."

At last, the revolution! In 1965, a year when Ian Whitcomb released his throwback stuttering song "N-N-Nervous" (on You Turn Me On), The Who offered "My Generation." No more pity or wisecracks--here stuttering is an act of violence against propriety, the lyric delivered by a pilled-up mod, spitting at and scorning everything he comes across, the apex of the performance being Roger Daltrey's majestically stammered "why don't you all EFFFFFFFFFFFFFFF-ade away!" (The Patti Smith Group's version, recorded live in 1976, delivers the obscenities the original seems desperate to say--it's a bonus track on Horses).

Pete Townshend later said he was inspired by Hooker's "Stuttering Blues" in writing "My Generation," thus debunking some myths about why Daltrey was stuttering the lyric--my favorite being that Daltrey was cold in the vocal booth and his teeth were chattering. (On one of the great '60s LPs, The Who Sing My Generation.)

"My Generation" helped inspire the vogue of stuttering lyrics in the late '60s and the '70s: Bowie's "Changes," "Benny and the Jets," "You Ain't Seen Nothin' Yet," "Bad to the Bone." But these songs simply took the hook of the stutter song and removed it from any sort of context.

It's tough, tough--tougher than tough!

It's worse than Benny Hill, and that's bad enough!

Something must be wrong with your vocal technique

When the 12-inch mix goes on for a week.

Morris Minor and the Majors.

"Stutter Rap," a 1987 Beastie Boys parody by the British comedian Tony Hawks, is a gag record that shuttles the stuttering song back into comedy, and it's about as crass and vicious as anything from the '20s. Still, it's pretty clever and was actually a top 10 hit in the UK and Canada. (On Complete '80s.)

Today, some twenty years after "Stutter Rap," the stuttering song hasn't developed any further, but it perseveres. There is Lord Brigo's "Stuttering Mopsy," from the late '90s, in which the premise of "Tongue Tied Jill" is recreated in calypso. And the R&B singer Joe Thomas' "Stutter," from 2001, is merciless--Joe accuses his woman of cheating just because she's stammering on the phone! (On Very Best of Pure R&B.)

Finally, Living Stereo's "Stammer"(on 2007's Introducing Living Stereo) rings the now-familiar changes of the genre, going from self-pity to isolation to fear to frustration. Such emotions never wane and neither apparently will the stuttering song--it will outlive us all.

End credits: Much is owed to Judy Kuster, whose web page on stuttering songs provided many inspirations for the songs in this post and features a number of further selections. Another resource was Marc Shell's Stutter, while Nick Tosches' Country was the source of the Billy Rose anecdote. Sheet music images from the Lester S. Levy Collection. And donate to the National Stuttering Association.