Southern Negro Quartette, I'll Be Good But I'll Be Lonesome.

Al Bernard, Frankie and Johnny.

Luigi and Antonio Russolo, Corale.

"Anonymous Jazz Band," Muscle Shoals Blues.

Sissle's Sizzling Syncopaters, Long Gone.

Lanin's Southern Serenaders, Shake It and Break It.

Ladd's Black Aces, Aunt Hagar's Children's Blues.

Mary Stafford, Strut Miss Lizzie.

Mamie Smith's Jazz Hounds (with Johnny Dunn), Old Time Blues.

...[W]e must strive for normalcy to reach stability. All the penalties will not be light, nor evenly distributed. There is no way of making them so. There is no instant step from disorder to order. We must face a condition of grim reality, charge off our losses and start afresh. It is the oldest lesson of civilization. I would like government to do all it can to mitigate; then, in understanding, in mutuality of interest, in concern for the common good, our tasks will be solved. No altered system will work a miracle. Any wild experiment will only add to the confusion. Our best assurance lies in efficient administration of our proven system.

President Warren G. Harding, inaugural address, 4 March 1921.

He writes the worst English that I have ever encountered. It reminds me of a string of wet sponges; it reminds me of tattered washing on the line; it reminds me of stale bean soup, of college yells, of dogs barking idiotically through endless nights. It is so bad that a sort of grandeur creeps into it. It drags itself out of the dark abysm of pish, and crawls insanely up the topmost pinnacle of posh. It is rumble and bumble. It is flap and doodle. It is balder and dash.

H.L. Mencken, on Warren G. Harding's inaugural address.

The King and Carter Jazzing Orchestra, Houston, January 1921.

The Southern Negro Quartette's "I'll Be Good But I'll Be Lonesome" is a head-on collision of styles. Nick Tosches aptly described the "stylistic schizophrenia" of the Quartette's 1921 records: call it a looser type of barbershop quartet singing, or early scatting, or a group burlesque of Al Jolson, or an ancestor to the Mills Brothers and The Coasters, or a taste of the hybrid that barely was: black country music.

Recorded ca. July 1921 and released as Columbia 3489 c/w "He Took It Away From Me"; on The Earliest Negro Vocal Groups Vol. 3 (an excellent compilation, which includes most of the Quartette's best tracks, like "Anticipatin' Blues" and "Sweet Mama.")

Dali, Voyeur.

While the folk ballad "Frankie and Johnny"(or "Frankie and Albert") dates to the 1890s or earlier, the first American recording of the song was the minstrel singer Al Bernard's 1921 Brunswick disc.

Much of the "canonized" lyric of "Frankie and Johnny" is based on an 1899 St. Louis murder case in which a 22-year-old African-American dancer named Frankie Baker killed her lover/pimp Albert (or Allen) Britt, allegedly over Britt's cheating. Bill Edwards:"When the stabbing was changed in legend to shooting is unclear, but early versions of the lyrics changed Al Britt to Albert, an easily explainable modification. However by 1912, with "Johnny" doing this and that in so many songs of that time (and possibly in some way related to the use of the term john as a prostitute's customer), Albert became Johnny, and both he and Frankie soon became legendary."

Frankie Baker was acquitted of all murder charges. She was working as a domestic in Omaha when Bernard's record came out; she subsequently moved to Portland, Oregon, and over the years she tried, in vain, to prevent films based on the case from being made (like She Done Him Wrong, with Mae West), while countless jazz, country and blues recordings of "Frankie" circulated. She died in a mental institution in 1952, unwillingly immortalized.

Recorded ca. May 1921 and released as Brunswick 2107 c/w "Memphis Blues"; on the now out-of-print That Devilin' Tune Vol. 1.

The Bohemian life: Charles Seeger, Constance de Clyver Edson and their children (2-year-old Pete is in Charles' lap), May 1921.

The Futurist Movement was heavy on painters and theoreticians and light on musicians. So the Italian Futurist painter Luigi Russolo said he would create Futurist music himself, using intonarumori--essentially, primitive white noise machines. There even were specific types: uluatori (howling machines), rombatori (rumbling machines), sibilatori (hissing machines), etc. None of them survived World War II. (From Daniel Albright's Modernism and Music.)

There is, however, one extant recording of the intonarumori, "Corale," composed in 1921 by Antonio Russolo, Luigi's brother, and recorded three years later. It is a piece of conventional orchestral music under which the intonarumori burble, groan and hiss: the result mainly conveys the sense of hearing a radio broadcast suffering from interference.

For Italy, the future was about to arrive at last. The leader of the Italian Futurists, Marinetti, had founded the Futurist Political Party in 1918, and a year later merged it with another new party--Benito Mussolini's Partito Nazionale Fascista; on Musica Futurista.

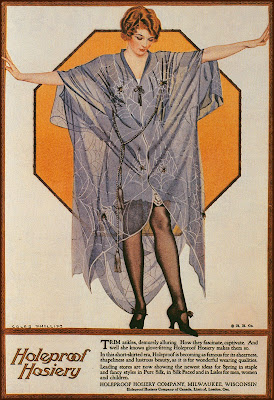

Detail from Stettheimer's Spring Sale at Bendel's.

In late 1921, Chicago's Marsh Laboratories, which would be the first American studio to produce electrical recordings, issued a test pressing on its own Autograph label. This was a jazz band recording of George W. Thomas' "Muscle Shoals Blues," credited to no one.

Eighty-eight years later, we still have no idea who played on this record. The most likely candidates are some members of Bennie Moten's Orchestra, but there is no conclusive evidence and there likely never will be. In our perpetual Google search of an era, when seemingly everything is known about anyone under the sun, it is a fine thing to have a record that still remains a mystery.

Recorded ca. fall 1921 and cut as Autograph 30, a test pressing (never released); on Ragtime to Jazz Vol. 2.

The Red Army takes Kronstadt, March 1921.

Noble Sissle, James Reese Europe's singer during Europe's 1919 tour, had inherited much of the band after Europe's murder. Sissle soon downsized, assembling a small group dubbed "Sissle's Sizzling Syncopators" that consisted mainly of Europe band veterans, including trumpet player Frank de Droite. Sissle's longtime collaborator Eubie Blake played piano.

The eight sides the sextet cut for Emerson in early 1921 were a showcase for contemporary black composers--along with Blake/Sissle originals like "Boll Weevil Blues," the Syncopators took on Spencer Williams, Clarence Williams and W.C. Handy (including what may be the first recording of Handy's "Careless Love" as well as his "Long Gone," the latter featured here).

Emerson signed Sissle to an exclusive contract just as Sissle and Blake started work on their revolutionary show Shuffle Along, which would be the first African-American-composed Broadway musical. So the Syncopators, whose records hint at the type of jazz chamber music later perfected by the likes of Duke Ellington, were left in the realm of the potential.

Recorded 18 March 1921 and released as Emerson 10365 c/w "Low Down Blues."

Sheeler and Strand, Manhatta.

Jimmy Durante, remembered today as a TV personality and the narrator of Frosty the Snowman, began as a jazz pianist. Durante was of the first generation of musicians to make a living out of playing jazz, in part by shuttling between NYC studios, playing the same piece three times in a day for three different labels.

Much of this hustle was due to the Russian-born bandleader Sam Lanin, who had become the intermediary between record labels and the growing pool of studio jazz players. So if a label wanted someone to record a new Broadway hit, they would call Lanin, who would quickly throw together a studio group and get the track cut in a couple days. And he'd being doing the same thing for another label at the same time.

So a session player like Durante was working in dozens of "jazz groups" simultaneously. Take the sextet "Lanin's Southern Serenaders," which featured Durante on piano and Phil Napoleon on trumpet, and "Ladd's Black Aces," which was pretty much the same group. Both Lanin's and Ladd's groups cut the exact same tracks, in nearly identical versions, within a few days in August 1921 for a series of different labels.

Lanin's Southern Serenaders' "Shake It and Break It" was released as Regal 9134/Emerson 10439, while Ladd's Black Aces' "Aunt Hagar's Children's Blues" was released as Gennett 4762/Star 9150. Or you could listen to Ladd's "Shake It and Break It" and Lanin's' "Aunt Hagar" and split the difference.; on Stomp and Swerve and Complete Ladd's Black Aces.

Munch, The Wave.

Mamie Smith's success led record labels to look for copycats or comparable singers, but since almost no label had any access to the Southern blues circuit (and singers like the young Bessie Smith), they first nabbed any black vaudeville singers they could find. One of these was Mary Stafford, whose first record was a take of "Crazy Blues" that's nearly as strong as Smith's hit version. The legend is that a Columbia Records exec heard Stafford singing "Crazy Blues" in a New York cabaret one night, and got her into the studio to sing it the following morning.

Overall, Stafford drew a poor hand in her career, only cutting only 14 sides in her life (including the debut recording of "Royal Garden Blues"). Columbia seemed disappointed in her, dropping her contract after six records, and Stafford's engineers and producers don't appear to have quite known what they wanted--some of her records are hot jazz band recordings in which Stafford's voice is a drowned-out afterthought, while others are thin, vocal-heavy stage weepies poorly translated to disc.

Here's one of the better ones: her version of Creamer and Layton's "Strut Miss Lizzie," recorded ca. May 1921 and released as Columbia 3418; on Document's exhaustive (and exhausting) multi-disc compilation of female blues singers in alphabetical order--this is from Volume 13, "R-S."

Johnny Dunn's first spotlit moment came in his performance on Smith's "Crazy Blues"--a moaning, wailing counterpart to Smith's vocal. Soon enough Dunn was getting work on his own, leading various editions of Smith's "Jazz Hounds" in 1921. Their records provide a decent snapshot of where jazz stood in the days just before Louis Armstrong left New Orleans to head north.

Dunn's "Old Time Blues" was cut on 1 February 1921 and released as OKeh 4296 c/w "That Thing Called Love"; on From Ragtime to Jazz Vol. 3.

Top photo: Miss Mary Eurana Ward christens the SS Eurana, which she sponsored, on 16 July 1921, Camden, NJ.

Next: Songmasonry

No comments:

Post a Comment