Eddie Hunter and Alex Rogers with Luckey Roberts, I'm Done.

Clarence M. Jones, Hula Lou.

Jimmy Blythe, Chicago Stomp.

Old Southern Jug Band, Hatchet-Head Blues.

The Mound City Blue Blowers, Red Hot!

Blossom Seeley with the Georgians, Lazy.

Viola McCoy with Fletcher Henderson's Jazz Five, I Ain't Gonna Marry, Ain't Gonna Settle Down.

Rosa Henderson & the Choo Choo Jazzers, Hard Hearted Hannah.

Gertrude "Ma" Rainey, Lucky Rock Blues.

Elkins-Payne Jubilee Singers, Ezekiel Saw De Wheel.

Vernon Dalhart, The Prisoner's Song.

The Wolverines (with Bix Beiderbecke), Riverboat Shuffle.

Jo Trent (with Duke Ellington), Deacon Jazz.

Francis Poulenc, Les Biches: Rag-Mazurka.

Jacques Ibert, Escales: Tunis-Nefta (modéré très rythmé).

Vincent Rose and His Orchestra, Helen Gone.

Wendell Hall, Comfortin' Gal.

Clarence Williams' Blue Five (with Louis Armstrong), Everybody Loves My Baby.

We're pioneers--new people--you can trust us.

Banner at a Soviet Young Pioneer camp, USSR, shown in Vertov's Kino-Eye, 1924.

VanDer Zee, "Marcus Garvey in a Regalia."

Two jokers and a piano player:

Eddie Hunter and Alex Rogers were singers, hustlers, stage pros: Rogers was an old collaborator of Bert Williams (he had written the lyrics of "Nobody" and other Williams standards) while the younger Hunter first drew notice for starring in and writing the libretto of How Come? (which got poor reviews, with critics claiming it baldly ripped off Sissle and Blake's Shuffle Along revue). Still, it was enough notoriety for Victor Records to offer Hunter (whose press agents were calling him "the colored Jimmy Barton") a contract, and late in 1923 he brought in Rogers and the pianist Luckey Roberts to cut four sides.

One of them was "I'm Done," a track some writers have called dated and corny (to the point where it's even been wrongly listed as a 1919 record in some references). Balls to that: "I'm Done" is prime American comic patter with modernity in the precision of its timing, in the way the actors bounce off each other, echo and undercut each other's words and slide into a common groove, with Roberts' stride piano dancing in the background. (Roberts, who held onto his copyrights, ran a popular bar and invested in NYC real estate, died a rich man.)

Recorded ca. November 1923 and released as Victor 19247 c/w "Bootleggers Ball." On George Williams and Bessie Brown No. 2.

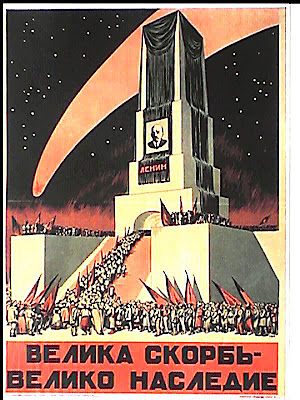

"Great is Grief, Greater Still is the Heritage": USSR poster commemorating the death of Lenin.

Two lost pianists:

Clarence M. Jones was a Chicago pianist (he accompanied Monette Moore and Laura Smith, among other blues singers), songwriter ("The Dirty Dozen," "Daddy Blues," "Trot Along," "Thanks for the Lobster") and bandleader (he headed the Wonder Orchestra at the Owl Theater, which sounds like something out of a Michael Chabon novel). Thomas Hennessey, in his From Jazz to Swing, claims that Jones and trumpeter Jimmy Wade opened the Chicago Loop district to black musicians. Jones (1889-1949) survives today only in the margins of histories--he remains an unknown influence, a ghost.

Jones' "Hula Lou," a solo piano variation of a then-popular stage novelty, doesn't appear to be as much an improvisation as it is a set piece, but it has a steady bounce to it and shows off Jones' fleet, dashing style. Recorded ca. April 1924 and released as Autograph 492 (later 499) c/w "Maybe (She'll Write Me, She'll Phone Me)"; on Archive of American Popular Music.

The Levys, a Jewish family on the island of Rhodes, 1924 (Rhodes Jewish Museum). Jews had lived on Rhodes since the 2nd Century BC. During World War II, all 2,000 Jews on the island were arrested and deported by the Nazis: most were sent to Auschwitz, and all but 150 were killed. Today about 40 Jews live on Rhodes.

Jimmy Blythe was born in Keene, Kentucky, in 1901 and died of epidemic meningitis thirty years later. He had moved to Chicago as a young man and spent the '20s as an accompanist on blues records (including Blind Blake and "Ma" Rainey), making some jazz tracks with Johnny Dodds and doing the occasional solo turn, though like Clarence Jones he primarily made a living by cutting hundreds of piano rolls for nickelodeons.

Blythe's "Chicago Stomp" shows just how strong a player he was, and makes one regret that the man only cut eight solo sides in his short life--"Stomp" is one of the first (if not the first) recorded examples of pure boogie-woogie piano, dominated by Blythe's rolling left-hand bassline.

Recorded in April 1924 and released as Paramount 12207 c/w "Armour Ave. Struggle"; on Boogie Woogie Blues.

"Miss Mary Bay likes her car because it is easy to park." Washington DC, January 1924 (Shorpy).

Two ramshackle collections:

The Old Southern Jug Band was an alias of Clifford Hayes' Dixieland Jug Blowers, working on another label. Allen Lowe calls the Jug Band's "Hatchet-Head Blues" one of the few surviving recordings of a brass- and string-band hybrid, with a banjo, jug bass and cornet all vying for attention.

"Hatchet-Head Blues" was recorded 24 November 1924 and released as Vocalion 14958 c/w "Blues, Just Blues, That's All"; on Clifford Hayes and the Louisville Jug Bands Vol. 1.

Weston, "Galván Shooting (Manuel Hernández Galván, Mexico)."

The Mound City Blue Blowers were founded by early jazz hipster and former St. Louis bellboy Red McKenzie (he played comb and sang) and included some developing talent, including Frank Trumbauer. Their first 1924 sides, especially "Red Hot!" are pretty fantastic stuff--who knew the kazoo could swing like this?

Recorded 14 March 1924 and released as Brunswick 2602 c/w "San"; on Hot Comb and Tin Can.

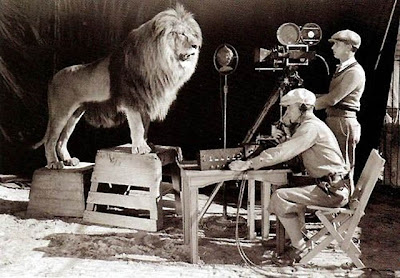

Slats the Lion being filmed for his latest MGM logo spot

Four blues stingers (even the icemen leave them alone):

Blossom Seeley was a vamp of early vaudeville--here's one description of a 1911 performance: "[Seeley] danced on the table to show off her shapely legs, and she used the platform to launch a dance craze. As an encore she performed the Texas Tommy, a dance originated by black vaudevillians in San Francisco's Barbary Coast. Theater critics were generally nonplussed by the way she toddled and shook, but Broadway audiences loved it" (Armond Fields and L. Marc Fields). She married a baseball player and later another vaudevillian, and lived long enough to appear on the Ed Sullivan Show.

Her hot version of Irving Berlin's "Lazy" was cut with The Georgians on 27 March 1924 and released as Columbia 114-D c/w "Don't Mind the Rain"; on Georgians 1923-1924.

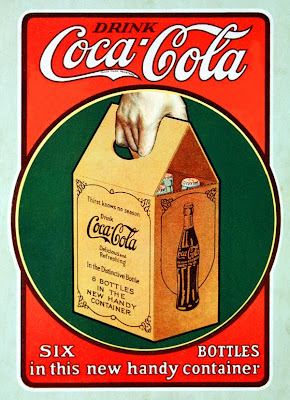

Progress: six-pack of Coke in milk-carton-shaped paper bag.

Viola McCoy, born in either Mississippi or Memphis ca. 1900, went through names as if they were pairs of shoes--she was born Amanda Brown, and recorded under Daisy Cliff, Bessie Williams, Fannie Johnson and Susan Williams, among others, suggesting that she probably still has some lost records out there. She had a refined contralto that could still deliver the blues. "I Ain't Gonna Marry, Ain't Gonna Settle Down" is a cold-eyed look at monogamy, which McCoy suggests is a lost cause. "It's nice to say that you are man and wife/but it's hard to find a pal who'll stick through life," she says, her eyes on the door.

"I Ain't Gonna Marry" was cut on 11 March 1924 with Fletcher Henderson (who had written the song with Ethel Waters) and released as Brunswick 2591 c/w the wonderfully-titled "If Your Good Man Quits You, Don't Wear No Black." On Viola McCoy Vol. 2.

Steichen, Gloria Swanson.

The outrageous Rosa Henderson cut a song in 1924 entitled (seriously) "Strut Yo' Puddy." From the same session is her version of "Hard Hearted Hannah," in which Henderson sounds like she could give Hannah a run for her money. It was recorded ca. September 1924 with the Choo Choo Jazzers and released as Ajax 17060; on Rosa Henderson Vol. 3.

Gertrude "Ma" Rainey starts the first verse of "Lucky Rock Blues" slowly, as if rousing her self from slumber. "Feelin'...kind of...melancholy," she moans, "made up my mind to go away," her voice more resonant than a saxophone, sinking lower than a trombone. The only one who can keep up with her is Tommy Ladnier, whose sharp 12-bar trumpet solo offers a taste of the New Orleans salvation Rainey is heading off to find.

Recorded March 1924 and released as Paramount 12215 c/w "Those Dogs of Mine"; on Ma Rainey Vol. 1.

Two commercial spiritualists (or professional hillbillies):

The Elkins-Payne Jubilee Singers were among the many black gospel groups who cut records in the '20s, as labels tried to find a commercial successor to the Fisk Jubilee Singers, which had established the "jubilee" style of gospel singing. Elkins-Payne were as much show-biz as they were spiritual: their leader, William C. Elkins, wasn't a minister but a former director of Bert Williams' vaudeville show. In their version of "Ezekiel Saw De Wheel," the lead female singer Eloise Uggams offers struggle and vitality, while the lead male singer (likely Elkins) is tradition and stasis.

Recorded 24 November 1924 and released as Okeh 40250 c/w "You Must Shun Old Satan" (good advice); on Complete Recordings.

DuBois, Mr. and Mrs. Chester Dine Out.

The sure 'nough Southerner talks almost like a Negro, even when he's white. I've broken myself of the habit, more or less, in ordinary conversation but it still comes pretty easily.

Vernon Dalhart.

Vernon Dalhart, born Marion Slaughter in Jefferson, Texas, in 1883, worked as a cattle puncher, studied at the Dallas Conservatory of Music and came to New York City in 1910, where he sang blackface minstrel songs and Puccini. His first recording for Edison was in 1917 and Dalhart soon gained a reputation for being a good dialect man (see above quote), recording everything from Hawaiian novelties to blackface numbers.

In 1924 Dalhart cut "The Prisoner's Song" and "Wreck of the Old 97," which became country music's first million-selling record. However it's barely what we today would consider "country," as Dalhart sings "Prisoner's Song" in a stately, slightly ridiculous tenor with only a trace of an accent. (Ralph Peer, who produced the record, later called him "a professional substitute for a real hillbilly.") Non-Southern audiences needed their first exposure to white rural music (which "Prisoner's Song" was for many) to not be too exotic, and the rich melody underpinned by basic guitar-and-fiddle accompaniment made the dose go down easy. The record's success inspired labels like Victor to head down South in search of new prospects, while Dalhart eventually wound up working as a hotel clerk in his old age.

Recorded 13 July 1924 and released as Victor 19427 c/w "Wreck of the Old 97"; on Country Gold Vol. 2 and 8,000 other compilations.

Davis, Odol.

Two precocious carpet crawlers:

Leon Bismark "Bix" Beiderbecke joined the Hamilton, Ohio-based jazz band The Wolverines (named after the Jelly Roll Morton song they played incessantly) towards the end of 1923, and his first-ever recordings came with the band a few months later when they had relocated to Cincinnati. Beiderbecke, all of 21 years old, was already developing new ways to play the cornet, such as emphasizing the horn's middle range and using subtler phrasing.

In April 1924, a young composer named Hoagy Carmichael invited the band to come to Bloomington, Indiana, as he had written a composition inspired by them and written specifically to showcase his friend Bix: "Riverboat Shuffle." The Wolverines' recording of the song is Beiderbecke's first great record, with a carefully crafted solo in which Bix circles through various melodic motifs and makes a glittering string of blue notes.

Recorded 6 May 1924 and released as Gennett 5454 c/w "Susie (of the Islands)"; on Bix and the Wolverines.

"Deacon Jazz," credited to Jo Trent and the Deacons, is one of the first recordings of a 25-year-old pianist and fledgling bandleader named Edward Kennedy "Duke" Ellington. Ellington had come to New York from Washington DC in 1922 and had spent years scrabbling around for work. By 1924, he had taken over Elmer Snowden's six-man band the Washingtonians and started getting regular gigs, including long engagements at the Kentucky Club.

Ellington and the Washingtonians cut their debut records in November 1924 for the tiny label Blu-Disc, including backing the singer/songwriter Jo Trent on Ellington's own "Deacon Jazz." The track doesn't have the full band, only Ellington, Otto Hardwick on C-melody sax, George Francis on banjo and drummer Sonny Greer, but Ellington's brief piano solo is a cloudburst of a thing, suggesting in miniature the riches to come.

Recorded November 1924 and released as Blu Disc T-1003 c/w "Oh How I Love My Darling"; on Black and White Piano.

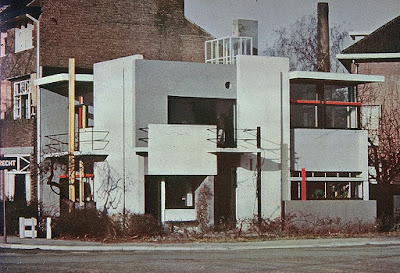

Rietveld Schröder House, Utrecht.

Two Frenchmen, one wayward, one stolid:

Francis Poulenc "invents his own folklore," Maurice Ravel once said, while Claude Rostand famously called him "half monk, half delinquent." Poulenc was a member of Les Six and a composer who wrote everything from art songs to ballets to oratorios (but unlike his Six colleague Darius Milhaud, he said he disliked jazz). His Les Biches, a ballet inspired by Watteau paintings of Louis XIV and his various women (sometimes in Louis XIV's deer park, hence Poulenc's title), is set in a modern-day hipster party attended by "twenty charming and flirtatious women" and "three strapping young fellows dressed as oarsmen." Poulenc's score consists in part of snarky rehabilitations of older musical types, such as the mazurka section featured here (meant to accompany a scene in which the oarsmen flirt with and then chase down the party's hostess, who has "yards of pearls and a meaningfully-long cigarette holder").

Premiered on 6 January 1924 by the Ballets Russes at the Theatre de Monte Carlo; this recording is conducted by Yan Pascal Tortelier and performed by the Ulster Orchestra.

Jacques Ibert, perhaps irritated by being left out of "Les Six," later formed a smaller club of composers with Six members Milhaud and Arthur Honegger. Ibert's Escales (Ports of Call), premiered on the same day as Les Biches, offers overseas exotica in place of Poulenc's dinner-party hijinks. "Tunis-Nefta," the second part of the piece, features an oboe imitating Arab music over a driving beat delivered by tympani and strings.

Premiered on 6 January 1924 in Paris; this recording is conducted by Eiji Oue and performed by the Minnesota Orchestra.

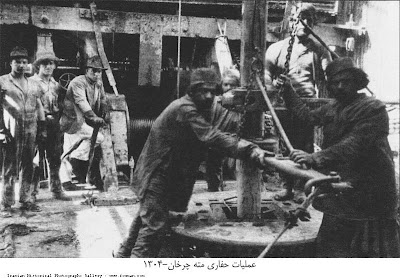

Oil drillers, Iran, 1924.

Three last songs, mainly about women:

Vincent Rose, born in Palermo, Italy, in 1880, headed a jazz dance band called the Montmartre Cafe Orchestra (it wasn't inspired by anything in Paris, but was the name of a Hollywood hangout for actors). While he was best known for hits like "Whispering," Rose's "Helen Gone" is a sparkplug of a track--fast, silly, irresistible. Recorded in Oakland on 12 June 1924 and released as Victor 19398; on Archive of American Popular Music.

Wendell Hall's "Comfortin' Gal" isn't the hayseed epic that his "Ain't Gonna Rain No Mo'" was but it still pops, with Hall's ukulele providing rickety support for his gloriously hokey vocal, which ranges from spoken asides to a dash of lunatic humming. Recorded 15 January 1924 and released as Victor 19207 c/w "It Looks Like Rain" (one of Hall's shameless sequels to "It Ain't Gonna Rain No Mo'").

And Clarence Williams' "Everybody Loves My Baby" has Louis Armstrong offering just one of the dozen of brilliant solos he reeled off that year (6 November 1924; OKeh 8181; on Portrait of the Artist).

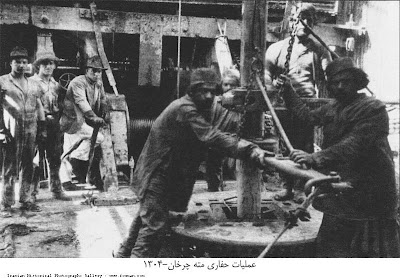

Oil drillers, Iran, 1924.

Three last songs, mainly about women:

Vincent Rose, born in Palermo, Italy, in 1880, headed a jazz dance band called the Montmartre Cafe Orchestra (it wasn't inspired by anything in Paris, but was the name of a Hollywood hangout for actors). While he was best known for hits like "Whispering," Rose's "Helen Gone" is a sparkplug of a track--fast, silly, irresistible. Recorded in Oakland on 12 June 1924 and released as Victor 19398; on Archive of American Popular Music.

Wendell Hall's "Comfortin' Gal" isn't the hayseed epic that his "Ain't Gonna Rain No Mo'" was but it still pops, with Hall's ukulele providing rickety support for his gloriously hokey vocal, which ranges from spoken asides to a dash of lunatic humming. Recorded 15 January 1924 and released as Victor 19207 c/w "It Looks Like Rain" (one of Hall's shameless sequels to "It Ain't Gonna Rain No Mo'").

And Clarence Williams' "Everybody Loves My Baby" has Louis Armstrong offering just one of the dozen of brilliant solos he reeled off that year (6 November 1924; OKeh 8181; on Portrait of the Artist).

1 comment:

What a great post re: 1924! Very nice selection of photos and well- written, knowledgeable musical commentary.

Post a Comment