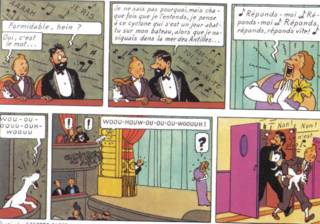

"a high-bred uptown fancy little dame"

Tex Williams and His Western Caravan, Smoke! Smoke! Smoke! (That Cigarette).

It's not the cigarettes that get Tex Williams riled up--he's a smoker himself. It's just that smoking consistently thwarts his other pleasures. An anthem of pure frustration with few peers; perhaps the Stones' "Satisfaction" is more desperate, but it's not as funny.

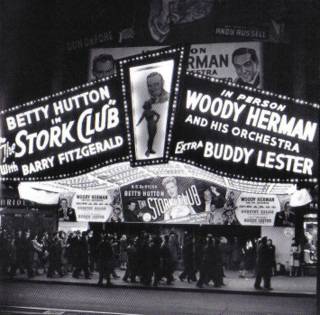

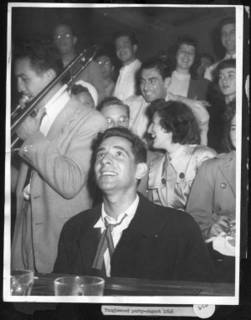

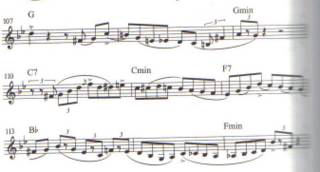

Merle Travis and Williams co-wrote "Smoke!", which became Williams' first and biggest hit. Sol "Tex" Williams had started as the singer in Spade Cooley's western swing band, and by '47 had stolen a good chunk of Cooley's band to form the gargantuan Western Caravan, featuring harp, accordion and steel guitar. "Smoke!" swings between jazz and country, with the walking bassline and blaring trumpet matched by Williams' classic country bass voice and the wheeling fiddle solo.

Recorded in Hollywood on March 27, 1947 and can be found here. (I hate to complain yet again about the damages done to the Smithsonian Classic Country LP compilation (from which I got "Smoke!"), but I must--not only is the CD version of this set now out of print, but it stunk on ice while it was available. Case in point--the compilers cut "Smoke!" while making space for two Alabama songs and "9 to 5".)

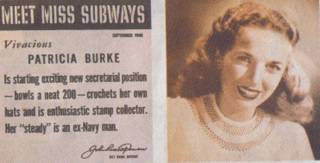

The '40s were the end of the Golden Age of smoking, with an early TV news broadcast, "Camel News Caravan", requiring its anchorman, John Cameron Swayze, to constantly have a cigarette burning while on air. And a NY Times Sunday magazine article in May '47, written by one W.B. Hayward, is entitled "Why We Smoke -- We Like It." The sidebar, purporting to show an opposing side, contains no mention of recent studies indicating links to heart disease, cancer and decreased longevity" As for Tex Williams, he would die of cancer in 1985.