The delivery room of the cool

Miles Davis Nonet, Jeru.

Had you been in New York, hanging around 5th Avenue and 55th St. during the summer of 1947, you might have noticed an odd lot of people going in and out of a small basement apartment located behind a Chinese laundry--a further investigation would have found it was barely an apartment at all, really, just a room where the building's pipes were housed, with just enough space for a bed and a few chairs.

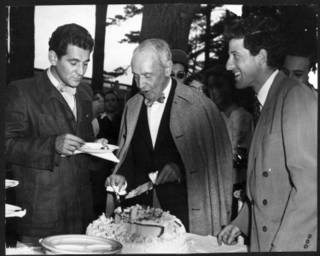

It was a curious group--an elegant, long-haired man who seemed to live in the place; a gangly red-haired giant carrying an enormous saxophone case; a nebbishy-looking guy who could have taught high-school science earlier in the day; a bearded, intense scholar; a bird-like girl with a snappy air; and a dapper, cool and menacing character who, if you had been in his way on the sidewalk, would have pushed you aside with a curt "Move."

The Miles Davis Nonet, a combo that exists more in influence than in evidence (only a dozen tracks recorded, two weeks of concerts played), emerged from a group of musicians hanging out in the apartment of the arranger Gil Evans. Many were in Claude Thornhill's big band, for whom Evans had done arrangments; others were already legends in bebop, like the drummer Max Roach and the trombonist J.J. Johnson.

It took Davis to turn a hobby into an enterprise. Having witnessed the often-chaotic Charlie Parker recording sessions, Davis was determined to be an innovative, efficient arranger and bandleader. As Gerry Mulligan would later say of Davis, "he called the rehearsals, hired the halls, called the players, cracked the whip." Davis also had a contract with Capitol Records, without which the Nonet would never have been recorded.

Davis was growing tired of bebop, and of his sideman's role in the Parker bands, and he found in the players gathering at Evans' place a group of like-minded souls. The veterans of Thornhill's band, like Lee Konitz and Mulligan, wanted to experiment with arrangements and expand upon the work of avant-gardists like Konitz's mentor Lennie Tristano; the boppers wanted to slow down bop's "steeplechase pace" (Gary Giddins' phrase), to incorporate soloists better into an ensemble, to bring counterpoint back into jazz.

The final group of nine's structure would be fairly radical--there was a rhythm section of piano, bass and drums, and then two sections of brass: a set group of Davis on trumpet, Konitz on alto saxophone and Mulligan on baritone sax; and a rotating group of players on instruments that were either out of fashion (trombone, tuba) or that had never been associated with jazz in the first place (French horn). This set-up allowed for many innovations (the tuba's presence, for example, freed Mulligan to use the baritone sax as a lead melodic instrument) that the band's arrangers--Mulligan, Davis, Evans, John Lewis and John Carisi--exploited to the hilt.

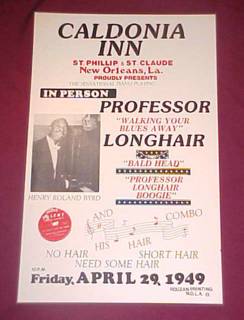

The result was a dreamy, Debussian blend of sounds. But it was also a commercial dud. The 78-rpm singles released from the Nonet's three recording sessions were bought only by fellow musicians, it seems; the Nonet's one major concert stand, a two-week booking at the Royal Roost in 1948, failed to impress patrons, who favored the Roost's other attraction, Count Basie.

It would take until the late 1950s, when the singles were compiled on an LP that a savvy Capitol exec called Birth of the Cool, for the Nonet to become immortalized. By that point, however, the Nonet's sound had become a basic language of jazz--heard in Mulligan's classic quartet with Chet Baker; in Lewis' Modern Jazz Quartet; in the legendary Davis/Evans LPs.

Here is Mulligan's "Jeru", recorded at the first Nonet session on January 21, 1949, and featuring solos by Mulligan on bari sax, Davis on trumpet, & Konitz on alto sax. Also featuring Kai Winding (trombone), Junior Collins (French horn), John Barber (tuba), Al Haig (piano), Joe Shulman (bass) and Max Roach (drums). Available on Birth of the Cool, one of the basic Jazz 101 records that remains fresh even after decades of playing.