White, The Orchard

"We must never forget that the President is seven years old," possibly apocryphal quote by a British ambassador about Theodore Roosevelt.

1902

Bedford Street, London, 1902

Dinwiddie Colored Quartet, Down On the Old Camp Ground.

Abdal Ali, Kurdish Death Lament.

Cantrell and Williams, Bye Bye Ma Honey.

Arthur Collins, Bill Bailey Won't You Please Come Home.

Will Marion Cook and Paul Laurence Dunbar, On Emancipation Day.

Len Spencer, On Emancipation Day.

Even if Gourlay had been a placable and inoffensive man, then, the malignancies of the petty burgh (it was scarce bigger than a village) would have fastened on his character, simply because he was above them. No man has a keener eye for behaviour than the Scot (especially when spite wings his intuition) and Gourlay's thickness of wit, and pride of place, would in any case have drawn their sneers. So, too, on lower grounds, would his wife's sluttishness. But his repressiveness added a hundred-fold to their hate of him...

It shewed itself in an insane desire to seize on every scrap of gossip they might twist against him. That was why the Provost lowered municipal dignity to gossip in the street with a discharged servant. As the baker said afterwards, it was absurd for a man in his 'poseetion.' But it was done with the sole desire of hearing something that might tell against Gourlay. Even Countesses, we are told, gossip with malicious maids, about other Countesses. Spite is a great leveler.

George Douglas Brown, The House With the Green Shutters.

Dinwiddie County is in southeast Virginia. Petersburg, the site of the last great slaughter of the Civil War, anchors one end of it. At the close of the 19th Century, the county was predominantly black in population--about 60%--and dirt poor. In 1898, philanthropists set up the Dinwiddie Normal and Industrial School in the hopes of improving the prospects of local blacks, and the school soon had a "jubilee quartet" that would tour nearby towns for fundraising.

By 1900, the Dinwiddie Colored Quartet (whose members routinely changed) had become a professional act, playing the vaudeville stage, and had acquired a manager, the Philadelphia-born Sterling Rex, who also served as first tenor. The Quartet, which joined a touring show called "The Smart Set," seems to have severed its ties with the Dinwiddie School by this point.

In October 1902, "The Smart Set" opened in Philadelphia, and during the run the Quartet went to the Victor Talking Machine Co.'s studio at Tenth and Lombard to record six tracks. This was one of the newly-formed Victor's first efforts, possibly its absolute first, to record black musicians.

"Down on the Old Camp Ground" was the first song cut, and it's masterful. While its structure is fairly basic (call-and-response verses, a gloriously harmonized chorus), it seems to contain multitudes, bearing the seeds of barbershop quartets, gospel and R&B. And while it is mainly a revival song, it is sewn through with bits of tomfoolery, in particular "down home" jokes in the final verse:

Down in the barnyard on my knees

I thought I heard that chicken sneeze

he sneezed so hard with a whooping cough,

that he sneezed his head and tail right off.

Recorded 29 October 1902, with Rex, J.M. Thomas, J.C. Meredith and H.B. Coyer, and released as Victor 1714; on Lost Sounds.

The Germans slip into the dying Ottoman Empire through its dreaming head, arriving in Zincirli (now Sam'al) in south-central Turkey, bearing Edison cylinders and a recording horn. They spend a few days on tours. One, a doughy young man from Saxony, finds that the dry weather has awoken his eczema and so he avoids the sun like a bankrupt dodging a creditor. The other, a grim mystic from Danzig, sleeps only three hours a night and spends the rest of the time reading Hesiod.

Their guide, a local rascal burlesquing as a learned man of the area, offers to find them talent. One afternoon, he approaches a Kurd named Abdal Ali. They want songs, the guide says. They might pay. I can't tell. Still, you should talk to them.

Ali has a wife and five children. The other morning he woke up from a terrible dream, and spat on his left side three times, the way the Prophet advises. He has an elaborate toothache which feels as though his lower gum has caught fire. He agrees to meet the Germans for tea.

They talk through an interpreter. The Germans want something that represents a pure aspect of the Kurdish spirit. Ali beams. He tells them a story about his grandfather which is entirely fiction. He never knew his grandfather and in fact is a quarter Dutch. The Germans stare at him. Ali smiles. Something of worship, or a death song, the interpreter (an oily little troll from Izmir) begs. They want something of importance.

So a day later, in the Danzig man's hotel room, Ali sits before the horn, which looks to him like a great conch shell grown from a stick. He clears his throat, sings. The Germans etch his voice onto wax, bring his voice home like a butterfly in a traveling case. The cylinder is cataloged, archived, forgotten. The Ottoman Empire falls, as does the German Reich (the cylinder winds up in East Germany after WWII); the Kurds endure a long century of murder.

In the waning years of the past century, after Germany's reunification, the Berliner Phonogramm Archiv begins digitizing its vast catalog of ethnographic musics, including Ali's lament. Ali's voice, his death song, now soars weightless, unmoored, existing merely now as a few digits of electronic space. Ali has achieved immortality, of a sort.

On Music! The Berlin Phonogramm Archiv 1900-2000.

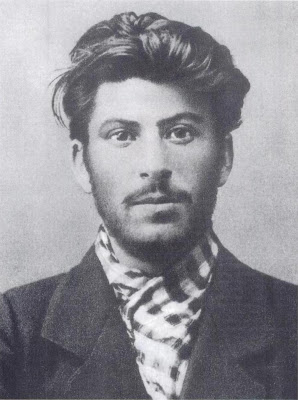

Portrait of the tyrant as a young man--Stalin, 1902.

Edgar Cantrell, born in Newport, Kentucky, in 1864, was taught to play banjo by a black family servant. When he moved to Chicago to work as a banjoist and singer, he met Richard Williams, a mandolin player of German ancestry. They formed "The Ragtime Duo" and came to the U.K. in 1902, touring around the musical halls (and playing the Lager Beer Room of London's Piccadilly Hotel), offering a grab-bag of ballads, rags, "coon" songs, cakewalks and reels.

While Cantrell and Williams seemed like the height of novelty for the U.K., their music was generally quite old-fashioned. "Bye Bye Ma Honey," for instance, was copyrighted in 1885 by Monroe Rosenfeld as "Good Bye My Honey I'm Gone" but it most likely had existed in some form for decades longer. Other songs in their repertoire were pre-Civil War.

The recording session that produced "Bye Bye Ma Honey" as well as their take on the inescapable "All Coons Look Alike to Me" was evidently a bit of a mess--the British recording engineers flummoxed by the wild, creaky American music, and the American performers getting drunk in the studio to take the edge off.

Recorded in London on 20 October 1902; released as Zonophone X-44000/Gram. Concert Rec. 4229; on Ragtime to Jazz Vol. 4.

"Bill Bailey Won't You Please Come Home" is a pure product of 1902, the year's top hit song. Written by Hughie Cannon, it's an example of how American popular songwriting and vocalizing was rapidly mutating. As Edward Marks once said, "The verse doesn't matter. Nobody ever remembered it anyhow," and that's true enough with "Bill Bailey," which is remembered almost entirely as just its hummable chorus (which disguises the grim fact that this is essentially a song about an abused woman begging her ne'er-do-well man to come back).

The song allegedly was written about a real minstrel performer who Cannon knew (and caroused with, as Cannon loved his booze and dope) and whose wife indeed threw him out of the house after he showed up drunk one too many times.

And Arthur Collins, while he still sings the tune roughly by today's standards, is very much singing in the new American vernacular--brassy, fearless and unconcerned with living up to classic parlor song expectations.

Recorded ca. May 1902 and released as Columbia 872; it can be found all over the place, including this archive of Collins tracks.

To tell the story of American composition in the early twentieth century is to circle around an absent center. The great African-American orchestral works that Dvořák prophesied are mostly absent, their promise transmuted into jazz.

Alex Ross, The Rest Is Noise.

The life of the African-American composer, impresario, violinist and conductor Will Marion Cook is a long study in frustration and perseverance. While it was Cook's ultimate fate to be a transition figure (as Ross writes, "he forms a direct link between Dvořák and Duke Ellington"), he didn't suffer in obscurity--he wrote a number of hit musical revues and mentored everyone from Sidney Bechet to Ellington.

Born in 1869, Cook from his youth had determined that he would be the first great black musician in American history. He was accepted into Oberlin, studied in Berlin and later with Dvořák, and returned to America in 1889 bursting with ambition. He intended to make a living as a performing violinist while writing classical works, including a proposed opera based on Uncle Tom's Cabin. After his Carnegie Hall debut, a critic hailed him as the "world's greatest Negro violinist." Enraged, Cook went to the critic's office, smashed his violin on the man's desk and exclaimed: "I am not the world's greatest Negro violinist--I am the greatest violinist in the world!" (This might be an apocryphal story, though Ellington included it in his memoirs.)

This sort of confidence slammed head-first against the virulent racism of the period (Plessy v. Ferguson was a recent Supreme Court decision), and Cook found little work in the classical music world. A black symphony orchestra that he had founded with Frederick Douglass' grandson went bust. So he began looking to musical revues. He collaborated with the poet Paul Laurence Dunbar on Clorindy (the first-ever black-composed Broadway show) and then in 1902 they collaborated on In Dahomey, whose show-stopper was "On Emancipation Day":

On Emancipation Day,

All you white folks clear the way...

When dey hear dem ragtime tunes

White folks try to pass fo' coons

On Emancipation Day.

Cook's mother was appalled. She had sent him to college, to Europe, and he had come back to write this? The crowds, however, howled for more. Performed by William Brown on Swing Along.

Sadly, unsurprisingly, "On Emancipation Day" was not recorded at the time of its composition by the African-American performers who delivered it on stage--Bert Williams and George Walker--but by, you guessed it, everyone's favorite desperate minstrel, Len Spencer. Whether Spencer appreciated the irony of him singing these lyrics is up to you to determine.

Recorded on 25 October 1902 and released as Victor 1710 (Spencer cut another take with Vess Ossman around the same time, and Collins also cut a version for Columbia).

1903

Bowery flophouse, 1903 (Shorpy)

Columbia Orchestra, Peaceful Henry (A Slow Drag).

Maurice Ravel, String Quartet in F Major: 2nd Movement (assez vif-très rythmé).

Scott Joplin, Weeping Willow Rag.

Air, Weeping Willow Rag.

They that walked in darkness sang songs in the olden days -- Sorrow Songs -- for they were weary at heart. And so before each thought that I have written in this book I have set a phrase, a haunting echo of these weird old songs in which the soul of the black slave spoke to men. Ever since I was a child these songs have stirred me strangely. They came out of the South unknown to me, one by one, and yet at once I knew them as of me and of mine...

What are these songs, and what do they mean? I know little of music and can say nothing in technical phrase, but I know something of men, and knowing them, I know that these songs are the articulate message of the slave to the world. They tell us in these eager days that life was joyous to the black slave, careless and happy. I can easily believe this of some, of many. But not all the past South, though it rose from the dead, can gainsay the heart-touching witness of these songs. They are the music of an unhappy people, of the children of disappointment; they tell of death and suffering and unvoiced longing toward a truer world, of misty wanderings and hidden ways.

The songs are indeed the siftings of centuries; the music is far more ancient than the words, and in it we can trace here and there signs of development.

W.E.B. DuBois, The Souls of Black Folk.

Sargent, Mrs. Fiske Warren (Gretchen Osgood) and Her Daughter Rachel.

Sousa's Band, which toured as much as it recorded, was a rare bird: most of the brass orchestras captured on disc in the early 20th Century were pure studio concoctions. These bands were pulled together out of jobbing theater musicians and the occasional classical orchestra slummer, and, more often than not, their attempts at syncopated popular music, whether ragtime or cakewalks, were dire.

There are a few exceptions. Columbia Records, one of the three major record labels of the 1900s, along with Victor and the declining Edison, had a solid house band led by Frederick W. Hager, who had good taste and who kept his orchestra nimble enough to preserve the rhythms and intricacies of ragtime compositions. Hager would survive well into the jazz age, producing Mamie Smith and Bix Beiderbecke.

Here is the Columbia Orchestra's take on E.H. Kelly's "slow drag" "Peaceful Henry." Kelly was a white Kansas City ragtime musician and vaudeville performer (he had a dog act), who named the piece after an old janitor he knew. The "orchestra" was actually quite small--just two cornets, trombones, and clarinets, a pianist, a piccolo (soon to be left behind by evolution), bass and drums. Recorded October or November 1903 in New York, and released as Columbia 1555; on From Ragtime to Jazz Vol. 4.

Stieglitz, Flatiron Building.

Maurice Ravel completed his first and only string quartet in April 1903, and in the following year he submitted it to two great French cultural institutions--the Prix de Rome and the Conservatoire de Paris. They both found it confusingly written and even Gabriel Fauré (to whom the piece was dedicated!!) thought the final section was "a failure." This reaction led Ravel to leave the Conservatoire for good.

The Conservatoire's dismissal of one of the finest string quartets of the 20th Century (only Bartok and Shostakovitch wrote better ones, IMO) seems, in retrospect, pretty damning evidence of the somnolent, palsied cultural establishment of Belle Epoque France.

"In the name of the Gods of music and in my own, do not touch a single note you have written in your Quartet," Debussy wrote Ravel. He didn't. Here is the second movement, a pizzicato whirlwind in which fandango rhythms vie with Ravel's austere classical harmonies, as performed by the Quartetto Italiano. And here is the complete score.

Scott Joplin composed "Weeping Willow Rag" at a time he was at odds with life: he had left Sedalia for St. Louis, had recently married a woman who he realized didn't like music, was feuding with his old publisher John Stark ("Weeping Willow" was published by St. Louis' Val Reis Music Co.) and was beginning to feel constrained by the standard ragtime format.

"Weeping Willow" is one of Joplin's loveliest pieces, and is one of his most tightly-structured compositions--the four sections are in two keys (G for the first two, C for the last) and feature common intervals and, in the case of the final two sections, repeated measures. The gorgeous trio section, with its sweeping rhythms and folk song chord progression (Bill Edwards hears the roots of "'Tain't Nobody's Business If I Do" in it), in particular soars. This recording is a piano roll (Connorized No. 10277) that Joplin made near the end of his life, in April 1916. (On The Entertainer.)

For a magnificent elaboration, here is the great jazz trio Air's take on "Weeping Willow," from their 1979 LP Air Lore (still not on CD). It opens with a parade-ground drum call by Steve McCall, who then launches into a three-minute solo, some of which is a variation on the "A" section of Joplin's rag (the other players eventually troop in). Henry Threadgill, on alto sax, improvises on the "B" section for five choruses, then repeats "A". He introduces the "C" section while McCall and bassist Fred Hopkins play stop time (just magnificent), then Hopkins takes four choruses to improvise on "C." Threadgill improvises on the trio section as well, then bores on into the final strain. In the words of Gary Giddins, "all of which sounds more complicated and cluttered than it is...the spirit suggests a naturalness at odds with the effort required."

Next: You Don't Own the State.

Sources: Tim Brooks, Lost Sounds; Wondrich, Stomp and Swerve; Ross, The Rest Is Noise; Mark Berresford, liner notes to From Ragtime to Jazz Vol. 4; Ceane O'Hanlon-Lincoln, County Chronicles; Giddins, Visions of Jazz (for much of the "Weeping Willow" analysis); the Abdal Ali bit is entirely made up.

No comments:

Post a Comment