Duke Ellington, Immigration Blues.

Bob Dylan, I Pity The Poor Immigrant.

Arthur Kylander, Siirtolaisen Ensi Vastuksia (The Immigrant’s First Difficulties).

Little Oscar Gang, Ole (A Norwegian Immigrant Arrives In the USA).

Pat White, I'm Leaving Tipperary.

Frank Quinn, An Irish Farewell.

The Pogues, Thousands Are Sailing.

Cherish the Ladies, The Back Door.

Big Audio Dynamite, Beyond the Pale.

Neil Diamond, America.

Arthur Collins, The Argentines, the Portuguese and the Greeks.

Kos Hristos, Xenos Ime Ki Iltha Tora (I Am an Immigrant and I Just Came Home).

Rita Abatzi, M'Ekapses Ameriki (America, You Ruined Me).

Dr. Antonio Menano, Fado do Emigrante (Song of the Immigrant).

Marilyn Cooper, Chita Rivera, et al, America.

Gaytan y Cantu, La Discrimination.

Juanito Valderamma, El Emigrante.

Gene Clark and Carla Olson, Deportee (Plane Crash at Los Gatos).

Buffy Sainte-Marie, Welcome, Welcome Emigrante.

The idea of escape was a simple one, but it hadn't occurred to me before. I had wanted only to get away from Washington and return to Bombay. But then I had become confused. I had looked in the mirror and seen myself, and I knew it wasn't possible for me to return to Bombay to the sort of job I had had and the life I had lived. I couldn't easily become part of someone else's presence again.

And one day, when I wasn't even thinking of escape, when I was just enjoying the sights and my new freedom of movement, I found myself in one of those leafy streets where private houses had been turned into business premises. I saw a fellow countryman superintending the raising of a signboard on his gallery. The signboard told me that the building was a restaurant, and I assumed the man in charge was the owner. He looked worried and slightly ashamed, and he smiled at me. This was unusual, because the Indians I had seen on the streets of Washington pretended they hadn't seen me; they made me feel that they didn't like the competition of my presence or didn't want me to start asking them difficult questions.

V.S. Naipaul, In a Free State.

Immigrant children, Ellis Island

I am the grandson of an Irish immigrant who came to the United States from Cobh in 1929. He emigrated with his mother, his sister and his brothers: they left my great-grandfather behind in Ireland, where he died. The family only discovered he was dead some fifteen years later, when one of my great-uncles, now in the U.S. Army, managed to get over to Cobh before D-Day.

As a child, before I left my grandparents' house each Christmas Eve, I would be sent to the basement to say goodbye to my grandfather and my great-uncles. There, in a dim, low-ceilinged room with wood paneling, the brothers would be gathered around the bar drinking shots. When I came down the stairs, they cheered, spoke to me in impenetrable brogues and gripped my hand as though to calculate my weight. This was my secret history--once a year I would descend into it for a few minutes, to be appraised and judged and wished well by the happy old men who seemed the custodians of the past.

A coat, a bag, a baby,

Status: refugee.

These are the people

of my family.

B.A.D., "Beyond the Pale."

My family's immigrant experience has been a series of misinterpretations and fumbles. I had thought my grandfather had come to the U.S. through Ellis Island, and so when I first moved to New York, I went there, paced the narrow hallways, imagined my ten-year-old grandfather maneuvering through them, felt small and humbled by history. It turns out that my grandfather, of course, never went through Ellis Island. He arrived in Poughkeepsie, or somewhere else--he never talked about it.

My parents brought him back to Cobh in the '90s and went on a quest to find the old family house, which allegedly was still standing. They drove around, turning up nothing, until my grandfather, likely exhausted, had them stop at an anonymous cottage. "That's it!" They took his picture in front of it. When they got back to the U.S., my great-aunt saw the photograph. "Oh, that's not the house at all." The real house was a few streets away, she guessed. He wasn't bothered.

At the high tide of my gloomy adolescence, I felt the need to connect to my roots, a process that mainly meant blasting Pogues songs like "Streets of Sorrow/Birmingham Six" and "Young Ned Of the Hill" ("A curse upon you, Oliver Cromwell/who raped our motherland"), and McCartney's "Give Ireland Back to the Irish," and occasionally feeling righteous and aggrieved about a conflict that I didn't comprehend.

At college in Boston, I wrote an essay on "the modern Irish immigrant experience" for a journalism class. I went to an Allston youth center that served as a crash pad for newly-arrived Irish, and found a kid my age named Desmond. He was sweet, had a extravagant nest of blonde hair, and loved watching Beavis and Butthead. He was from County Offaly ("pronounced AW-FULL-Y") and had come to Boston simply looking for work, for something better to do. Talking about what it meant to be an immigrant didn't interest him in the least, and his traditions seemed ridiculous. "You mean like sittin' out in a field with your old pa playin' the tin whistle?"

Joseph Stella, Immigrant Girl, Ellis Island (1916)

I also called a newspaper columnist named O'Baogill, who wrote for a local weekly that catered to the Irish expat community. The paper was unapologetically pro-IRA and was filled with grim articles about martyrs and retribution. I mispronounced his name as I introduced myself. "OH-BWEEL! OH-BWEEL!" he barked. He soon settled into his obsessions. "The British need to give up the ghost of colonialism," he said, about a dozen times in the course of the interview.

The longer he spoke, the more I wanted to get off the phone. I had found my subject, an American obsessed with his Irish heritage, and he was insufferable. If my grandfather's basement had been a cabinet of curiosities, holding the promise of an unclaimed past, this man just sounded as though he was deep in a box, trapped in some grievance of his own imagining.

I finally went to Ireland in 2001: to Limerick and Dublin, and of course, Cobh. I found my grandfather's old school, and not his house. It was an odd trip. When I first arrived in Ireland I quietly held the same delusive hope that many children of immigrants have upon returning to the homeland--that somehow, in some inexplicable way, the mother country will welcome you effusively, as if your absence had left the place so bereft that perfect strangers will sing your name out in the streets.

As the days went on, and as we indulged in various tourist shenanigans, like attending a musical revue that consisted of, in part, a teenage kid sitting with her old pa playing the tin whistle, I became convinced the Irish actually hated me, and I began to feel like an impostor without the dignity of a ruse.

One afternoon in Waterville, I was in the village pub drinking a Carling when I saw a man about my age sitting across the room. He looked as though he had just gotten off work, and was sprawled on a bench with a pint in front of him and a laborador retriever trying to climb into his lap. He slapped the belly of the dog a few times, which made the dog yelp happily. He hoisted his pint, looked around absently. What he made of me was nothing, or less than nothing. Just another family-tree tourist.

I thought for a moment: could his have been my life? If my grandfather had never left, if some variation of me had somehow come into being in Cobh in 1972. It seemed enticing, in the way that imagining your death can seem enticing, and then it just felt horrible, offering the prospect of some grotesque shadow existence. I felt closed in, swamped by the catastrophic power that the past holds. I soon left the pub; a few days later, I went home.

There have been a great many immigrant songs over the past century, as it's a natural subject: to be an immigrant is to voluntarily cast yourself into exile, to carve yourself in halves; to be the son or daughter of an immigrant is to have the sense that your house is built on sand. Call it the immigration blues, as Duke Ellington did. (Ellington's 1927 track, featuring one of the first great recorded Bubber Miley trumpet solos, is on Early Ellington).

Bob Dylan's masterpiece John Wesley Harding is a set of inscrutable parables. Why does Tom Paine own a slave, and why is he sorry for what she's done? Who sent St. Augustine down to death? Why was the drifter on trial? One of the most gnomic is "I Pity the Poor Immigrant," which, upon an initial listen, seems cold, even nativist, in its sentiments:

I pity the poor immigrant

Who wishes he would've stayed home,

Who uses all his power to do evil

But in the end is always left so alone.

That man whom with his fingers cheats

And who lies with ev'ry breath,

Who passionately hates his life

And likewise fears his death.

It's reminiscent of the scene at Lake Tahoe in The Godfather Part II, when the corrupt Senator Geary sneers at Michael Corleone:

I don't like your kind of people. I don't like to see you come out to this clean country with your oily hair, dressed up in those silk suits and trying to pass yourselves off as decent Americans. Oh, I'll do business with you, but the fact is that I despise your masquerade. The dishonest way you pose yourselves, yourself and your whole fucking family.

Yet "I Pity The Poor Immigrant" can't be divined that easily: it retreats the more you peer into it. The song's narrator may well be God, who, with regret but scant compassion, watches as his wayward children stumble around in error.

Ellis Island art

Why should the Palatine Boors be suffered to swarm into our Settlements and, by herding together, establish their Language and Manners to the Exclusion of Ours? Why should Pennsylvania, founded by the English, become a colony of Aliens, who will shortly be so numerous as to Germanize us instead of our Anglifying them, and will never adopt our Language or Customs, any more than they can adopt our Complexion?

Benjamin Franklin, Observations Concerning the Increase of Mankind (1755).

Arthur Kylander, born in Lieto, Finland, in 1892, emigrated at the start of the First World War, becoming a logger in Oregon and later joining the Wobblies (he translated Joe Hill's songs into Finnish). By the '20s he was a popular musician in the Finnish-American community, and had a few recording sessions in New York, one of which produced "Siirtolaisen ensi vastuksia," which begins "I left Finland behind me/like others I was headed to the golden land of the west." The first words the immigrant hears are "no, sir." Recorded in 1928.

The Little Oscar Gang were a regional band that played the Upper Midwest in the '40s and '50s, led by Aone Hoberg Anderson and her husband Ed Hoberg. The players were mostly descended from Norwegian immigrants, and their "Ole," from 1952, is the sad tale of a latter-day Norwegian greenhorn and his travails in America.

Both of these tracks, and some others to come, are on the fantastic compilation Stranded in the USA, compiled by Cristoph Wagner and issued by Trikont in 2004. I absolutely recommend picking it up.

The Irish are the masters of self-pitying immigration songs--there are songbooks full of them. Here are four:

Pat White was born in Chicago in 1860, the son of Irish immigrants, though he spent much of his professional life pretending that he had just gotten off the boat. He worked the medicine shows and vaudeville theaters, sometimes billed as Pat White and Gaiety Girls (a group of barely-clothed dancers) and in 1928 recorded "I'm Leaving Tipperary."

By contrast, Frank Quinn was the real deal--he emigrated from Longford, Ireland, to New York in 1903 and, unsurprisingly for a young Irish man, joined the NYC police force. He moonlighted by playing music in neighborhood theaters. (His first records for Vocalion were billed as "Patrolman Frank Quinn.") His "An Irish Farewell," recorded in 1931, is a typical Irish wake, in which departing emigrants are bid farewell the night before taking the boat to America, with the tacit acknowledgment that the departed will never be heard from again. (Again, both are on Stranded in the USA).

"where the hand of opportunity/draws tickets in a lottery"

And two more modern takes: The Pogues' "Thousands Are Sailing" is from 1988's If I Should Fall From Grace With God. "Then we raised a glass to JFK, and a dozen more besides/when I got back to my empty room, I suppose I must have cried."

Cherish The Ladies is an all-female Irish-American folk group whose members (often rotating) are mainly the American-born daughters of Irish immigrants. "The Back Door," from 1992, is their best-known song and the title track of their debut LP. Upcoming tour dates.

Until the First World War, the Bowery and the whole Lower East Side were the districts where the immigrants chiefly came to live. More than a hundred thousand Jews arrived there every year, moving into the cramped, dingy apartments in the five- or six-storey tenement blocks...In the autumn, the Jews would build their sukkahs on the fire escape landing, and in summer, when the heat hung motionless in the city streets for weeks and it was unbearable indoors, hundreds and thousands of people would sleep outside, up in the airy heights and even on the roofs and sidewalks or the little fenced-off patches of grass on Delancey Street and in Seward Park. The whole of the Lower East Side was one big dormitory. Even so, the immigrants were full of hope in those days, and I myself was by no means despondent...

W.G. Sebald, The Emigrants.

Big Audio Dynamite's "Beyond the Pale" is a fairly autobiographical song by Mick Jones, the son of a Welshman and a Russian Jew (Jones allegedly vowed never to set foot on stage with the Sex Pistols after Sid Vicious wore a swastika shirt): Jones had lived as a child with his immigrant grandmother, whose memories turn up in the lyric. He wrote "Beyond the Pale" with his old bandmate Joe Strummer, on the underrated No. 10, Upping St.

And yes, Neil Diamond (another Russian Jewish musician)'s "America" was an inescapable choice for this topic, and yes, despite its bombast, the song still can get to you sometimes. On The Jazz Singer.

The United States is invaded by aliens, thousands of whom constitute so many acute perils to the health of the body politic. Modernism is of precisely the same heterogeneous alien origin and is imperiling the republic of art in the same way...By the time the cubists came along there was an extensive body of flabby-mindedness ready...These movements have been promoted by types not yet fitted for the first papers in aesthetic naturalization--the makers of true Ellis Island art.

Royal Cortissoz, art critic, 1923.

Arthur Collins' 1920 version of Arthur Swanstrom and Carey Morgan's "The Argentines, The Portuguese and the Greeks" is a novelty song, but it sums up the mood of the era, in which many "native" Americans believed the country was being flooded with too many people from the wrong side of Europe (and anywhere in Asia), culminating in the Immigration Act of 1924.

Augustus Sherman, North African Immigrant, Ellis Island (1910)

"Xenos ime ki iltha tora [Ι am an immigrant and I just came home)" was recorded in 1909 by Kos Hristos, of whom I know nothing. On Sound Documents of Greek History.

The legendary Greek singer Rita Abatsi recorded "M'Ekapses Ameriki" in the mid-'30s. It's the tale of a Greek woman whose fiancee has gone off to America to seek his fortune and has promised he will return, but he never does. Now, she sings, she is old, alone and betrayed. "America, you ruined me, with all your dollars." (Also on Stranded in the USA.)

And Dr. Antonio Menano, from Portugal, offers "the fado of the emigrant," an apology and farewell that many an immigrant likely told the ones they were deserting. "I'll leave you/but that doesn't mean I'm not present any more/only my body leaves/my thoughts will stay here." Recorded in Berlin ca. 1935.

Along with updating Romeo and Juliet, West Side Story is a take on the rapid transformation of New York in the decade after the Second World War, when the Puerto Rican population went from 13,000 in 1945 to nearly 700,000 in 1955. "America," sung by Marilyn Cooper and Chita Rivera, is from the original Broadway cast recording of West Side Story.

Juan Gaytan and Fransisco Cantu were the sons of Mexican immigrants, a guitarist duo who played the Southwest in the '30s and '40s. Their "La Discrimination," recorded around 1950, is a bitter testimony to the brutality inflicted on Tejanos in Texas and other states. "Just think about the discrimination/that we Latins suffer in the fields and towns/We are looked upon as sheep."

Juanito Valderamma, a Spanish flamenco singer, wrote "El Emigrante" in 1949, about the many thousands of Spaniards who fled the country after the Fascists won the civil war. "I wrote it when I saw Spaniards weeping as they fled abroad. I could have called it 'El Exiliado' ['The Exile'] but I'd have been shot," he said later. This version was recorded around 1950; on pretty much any Valderamma compilation available, like this one.

And Woody Guthrie's "Deportee" was written after Guthrie had read about a plane crash in Los Gatos canyon, near Fresno, California, in January 1948. Guthrie was struck by the fact that newspapers and radio didn't mention any passenger names, as the passengers were all illegal Mexican mmigrants being deported (and whose bodies were put in a mass grave), instead simply calling the 28 dead "deportees" while taking pains to name the four native-born crew members also killed.

A decade or so later, a schoolteacher named Martin Hoffman set Guthrie's words to music, and the track was soon performed by Pete Seeger and, later, the Byrds. Gene Clark recorded the version here with Carla Olson in 1987--it was one of Clark's last recordings before his death in 1991. On So Rebellious A Lover.

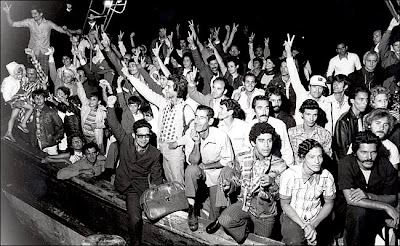

The Mariel boatlift, 1980

What evil could possibly happen? There were my books: could they be destroyed? My house--could I be dispossessed of it? There were my friends--could I ever lose them? I thought without fear of death, of illness, but not the remotest picture came into my mind of what I was still to live through. That homeless, pursued, hunted, as a refugee I would again have to wander from land to land, across oceans and oceans, that my books would be burned, forbidden, proscribed, that my name would be posted in Germany's like a criminal's and that those friends whose letters and telegrams lay before me on the table would pale if by chance they encountered me.

Stephan Zweig, The World of Yesterday.

Finally, Buffy Sainte-Marie, as a descendant of the First Nations, welcomes all of us recent immigrants. From her out-of-print 1965 record Many a Mile; find on The Best Of Vol. 2.

Next: The Life of Violets.

No comments:

Post a Comment