1926:

Jelly Roll Morton, Doctor Jazz.

George Gershwin, Sweet and Low Down.

Erskine Tate's Vendome Orchestra (with Louis Armstrong), Stomp Off, Let's Go.

Arizona Dranes, It's All Right Now.

Smith's Sacred Singers, Where We'll Never Grow Old.

Crockett Ward and His Boys, Sugar Hill.

Jack Buchanan and Elsie Randolph, Let's Say Goodnight Till It's Morning.

I long to devour the whole gigantic globe, which I have loved and wept over, and which surges all about me, travels, commits suicide, wages wars, floats in the clouds above me, breaks into nocturnal concerts of frog music in Moscow’s suburbs, and is given me as my setting, to be cherished, envied and desired...God, how I love all that I have never been and never will be, and how sad that I am I.

Boris Pasternak, letter to Maria Tsvetayeva, 1 July 1926.

Away with hard times and war: there’ll be enough of that to come. It’s 1926—fix a drink and dance.

Jelly Roll Morton claimed to have invented jazz, which is nonsense, but he was the finest jazz arranger and synthesist of his generation (which included Fletcher Henderson and King Oliver). Morton took the New Orleans style of ensemble playing and rarefied it into a music of inspired contrasts--rhythmic, melodic, textural. At times, it seems like every fourth bar of a Morton composition brings something radically new. Part dancing master, part juggler, Morton would drill his players until they knew their cues and how their solos should fit into the larger puzzle (not just for Morton's compositions, as often Morton's "arrangements" of other composer's songs entailed greatly re-writing them).

By 1926, the Victor Record Co. had perfected the electrical recording process, which allowed for far better-recorded tracks (due in part to the use of microphones and ampilifiers) with less surface noise and greater dynamic range. So in the latter months of 1926, Morton and his Red Hot Peppers (who were a collection of top players from a number of Chicago groups, some of whom were also recording with Louis Armstrong’s Hot Five) recorded a dozen or so tracks for Victor that are still startling in their genius: “Black Bottom Stomp,” “The Chant,” “Sidewalk Blues,” “Dead Man Blues,” “Grandpa’s Spells.”

O'Keefe, The Shelton, With Sunspots

My favorite is "Doctor Jazz"--it might be my favorite recording ever. It’s hard to reduce to words the vitality of this track--the way it sounds like Omer Simeon’s clarinet could stay on one note forever until he’s slapped upside the head by the drummer, or the boozy insouciance of Jelly Roll’s vocal, or the way each player snaps into place at the end.

Recorded in the Webster Hotel in Chicago on December 16, 1926. With George Mitchell (cornet), Kid Ory (trombone), Simeon, poss. Barney Bigard and Darnell Howard (clar), Johnny St. Cyr (banjo, guitar), John Lindsay (string bass) and Andrew Hilaire (d).On Birth of the Hot.

families just don't go to plane crashes together anymore

While George Gershwin the composer is renowned, George Gershwin the pianist is still overlooked, which is a shame, as Gershwin played with vibrancy and an excellent sense of rhythm. He wasn't much of an improviser, but compensated by effortlessly blending every form of music that caught his ear--hot jazz, classical "art" songs, Broadway ballads.

He wrote "Sweet and Low Down" for the 1925 show Tip Toes (which also featured "That Certain Feeling"), and recorded it as a jaunty piano solo on July 6, 1926. On Gershwin Plays Gershwin.

Lang's Metropolis

Louis Armstrong's greatest work in the 1920s was in his small band recording sessions, the Hot Fives and Sevens, from which came masterpieces like "Potato Head Blues," "West End Blues," "Weather Bird" and others. But to concentrate solely on the Hot Five sessions is to miss Armstrong's larger cultural presence--how many of his contemporaries actually heard him.

"Stomp Off Let's Go" finds Armstrong serving as hired gun in a working dance band, in this case for Erskine Tate's Vendome Orchestra. Tate's band played at Chicago's Vendome Theater, and this track is a much better indication of "contemporary" hot jazz than Armstrong's Hot Five records. Armstrong is all over the track, in the vanguard of the ensemble playing as well as providing a fine stop-time solo, backed by percussionist Jimmy Bertrand, who was a prime influence on Lionel Hampton. The other standout player on this track is the pianist Teddy Weatherford, who was considered the equal of masters like Earl Hines but who, in 1926, took off for Asia and never returned, dying in Calcutta in 1945. (Info from Dan Morgenstem.)

Recorded in Chicago on May 28, 1926, and featuring James Tate (t), Eddie Atkins (tb), Angelo Fernandez (cl), Stump Evans (alto and bari sax), Norval Morton (tenor sax), Frank Etheridge (banjo) and John Hare (brass bass). On Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man.

The '26 Bentley 3-liter

I have read and pondered over your article and I feel that you missed the spirit of the average woman…that the statistics veiled the ideal we hold. I am one of the hardworking mothers, with primitive equipment and seven little ones ranging from the baby in arms to a twelve year old. We have practically nothing of value except a good sewing machine.

You mention the automobile as a luxury…The automobile is one of the tools of life now. My sisters live in small towns near larger cities, their husbands go to and from work in their automobiles. The fact that their cars can also mean pleasant hours no more detracts from their usefulness than the fact that old Kate and Fannie were often hitched up to take the family to the fair.

Then the radio, the piano, and so on, elbowing the washboard and tubs, are viewed with amazement. Here is where you lost the meaning of it all…Why did the mother consent to the purchase of these things? The radio is her answer to the call of the pool hall. Her daughters must have the advantage of piano instruction, that their lives be brighter and better than her own. She stands deep in mire herself, but holds her family up in the sunlight.

"Mrs C.S.,” letter of March 1926, in response to “What Women Want in Their Homes,” an article in the Women’s Home Companion, which had argued that because women were not buying new household equipment, but “luxuries” like cars and radios instead, that women had no desire to escape the drudgery of their lives.

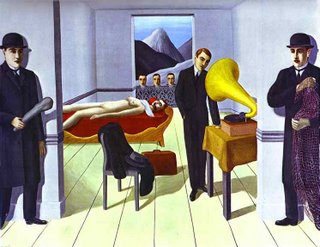

Magritte, The Menaced Assassin.

Arizona Dranes was born in Greenville, Texas (dates range from 1894 to 1900) and grew up singing and playing the piano, first at the Texas Institute for Deaf, Dumb and Blind Colored Youth (Dranes was born blind) and then at the Church of God in Christ in Austin. While she had a compelling voice, her barrelhouse piano playing is of another order in its muscle and rhythmic sense. Before Dranes, African-American gospel was generally performed without musical accompaniment; after Dranes, piano became a requirement. Her piano stylings, marked by "percussive fits and seizures" (Allen Lowe), can be heard in descendents like Little Richard.

"It's All Right Now", recorded on June 17, 1926, seems to be creating modern gospel and soul all at once. Sadly, I don't think there is any decent compilation of Dranes' material in print on CD--however, you can find much of her best stuff on JSP's Spreading the Word set.

Smith's Sacred Singers, a Georgia-based gospel quartet, were a greatly popular singing group in the South during the '20s. Led by the Methodist teacher J. Frank Smith and a rotating cast of vocalists, Smith's Sacred Singers came out of the amateur "shape note" singing tradition of many Southern churches, and by the time the Singers began recording in 1926, they had achieved a compelling, masterful sound.

"Where We'll Never Grow Old", c/w "Picture from Life's Other Side," was reportedly the best-selling record of Columbia's 15000-D "old time music" series, and inspired other record companies to seek out Southern gospel performers.

The Singers on this track are Smith, Rev. M.L. Thrasher, Clyde B. Smith and Clarence Cronick, with Mrs. T.C. Llewellyn on piano. Recorded in Atlanta on April 23, 1926. Appallingly, Smith's Sacred Singers' work never has been collected in any real sense on either LP or CD, though I believe "Where We'll Never Grow Old" is on a CD called The Columbia Label--Classic Old Time Music, which may be ordered here.

"If you wanna get your eye knocked out/if you wanna get your fill/if you wanna get your head cut off/then go to Sugar Hill." Now that's a lyric.

Crockett Ward and His Boys, who recorded "Sugar Hill," were exactly that--the fiddler Crockett Ward and his three sons, Fields (guitar and vox), Sampson (banjo) and Curren (autoharp). They hailed from Ballard Branch, Virginia, close to Galax, which was known for the "Galax Sound"--a brand of intense string band playing featuring high, nasal vocals.

"Sugar Hill" is a perfect string band dance number, with a repetitive verse form, driving fiddle and an accented fourth beat in every measure; it's sung with gusto by Fields Ward. In the 1930s, the Wards joined forces with the fiddler Uncle Eck Dunford, and became known as the brilliantly-named Ballard Branch Bogtrotters. (Much more info on the Bogtrotters can be found on Old Blue Bus, which featured them earlier this year).

Find "Sugar Hill" on Rural String Bands of Virginia.

What strikes you at first, however, when you are new to this more primitive form of burlesque, is the outward indifference of the spectators. They sit in silence and quite without smiling and with no overt sign of admiration toward the glittering and thick-lashed seductresses...The audience do not even applaud when the girls have gone back to the stage; and you think the act has flopped. But as soon as the girls have disappeared behind the scenes and the comedians come on for the next skit, the men begin to clap, on an accent which represents less a tribute of enthusiasm than a diffident summons for the girls to appear again.

The audience never betray their satisfaction so long as the girls are there...They have come to the theater, you realize, in order to have their dreams made objective, and they sit there each alone with his dream. They call the girls back again and again, and the number goes on forever.

In one of the numbers, the girls come out with fishing rods and dangle pretzels under the noses of the spectators; the leading ladies have lemons. The men do not at first reach for them; they remain completely stolid. Then suddenly, a few begin to grab at the pretzels, like frogs who have finally decided to strike at a piece of red flannel...

Edmund Wilson, article on the National Winter Garden Burlesque Show, 18 August 1926.

The party's wound down, but you don't want to leave just yet. Jack Buchanan and Elsie Randolph can empathize. "Let's Say Goodnight Till It's Morning" is a fine example of the light, dazzling British pop music that was crafted between the wars (though in this case, the songwriters are the Americans Jerome Kern (music) and Otto Harbach and Oscar Hammerstein (lyrics)).

By the early '20s, Jack Buchanan was an established stage star in both the U.K. and America, and in 1926, for the musical Sunny, he first teamed up with Elsie Randolph. Using the formula Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers would later perfect, he gave her class, she gave him sex appeal. They had a wonderful rapport (eventually getting romantically involved off-stage), which you can hear in "Let's Say Goodnight," a song that features one of Kern's loveliest choruses and ends with a minute or so of foot-stomping.

The U.K. premiere of Sunny was on October 7, 1926 (it had premiered the year before in New York) and the U.K. original cast recording can be found on Sunny.

No comments:

Post a Comment