1946:

Spade Cooley and His Orchestra, Three Way Boogie.

Delmore Brothers, Boogie Woogie Baby.

Henry "Red" Allen, Get the Mop.

Big Joe Turner, My Gal's a Jockey.

Moon Mullican, New Pretty Blonde (New Jole Blon).

Edith Piaf, C'est Pour Ça.

Billie Holiday, Big Stuff.

Peggy Lee, I Don't Know Enough About You.

Charlie Parker Septet, A Night in Tunisia.

The Bebop Boys, Webb City.

Floyd Tillman, Drivin' Nails in My Coffin.

Dodo Marmarosa, Dodo's Bounce.

A lot of us were disappointed in the Britain that we came back to...nobody could make it change overnight into the Britain we wanted.

Mrs. Winnie Whitehouse, in Paul Addison's Now the War Is Over.

We're now heading through already-charted territory, as these are the years "Locust St." has already covered once. However, the first go-round at 1946 (which can be found here) was quite minimal by this blog's current verbose standards.

By the early '40s, Spade Cooley, born in Pack Saddle Creek, Oklahoma, in 1910, had become a major rival to established Western swing bandleaders like Bob Wills, and in 1947 Cooley got his own television show, which at one time attracted 75% of the Los Angeles viewing audience.

"Three-Way Boogie," a track centered around the accordion playing of Pedro de Paul, comes from the late autumn of Western swing, the height of Cooley's success. But Cooley's popularity waned in the '50s, and his story has a terrible ending--in 1961, he brutally murdered his estranged wife and was sentenced to life in prison. Granted leave eight years later, he played a benefit show and dropped dead from a heart attack backstage.

"Three Way" was recorded in Hollywood on May 3, 1946. With Cooley on violin, Johnny Weiss (take off guitar), Joachquin Murphy (steel), Smokey Rogers (rhythm guitar) Spike Featherstone (harp), Eddie Bennett (p), Deuce Biggins (b), Muddy Berry (d). On the aptly-named Swinging the Devil's Dream.

The Delmore Brothers, like the Blue Sky Boys profiled in the 1936 entry, were among the top brother duet groups of prewar country music. Yet after the war, the vogue for such duos began to fade. Some, like the Monroes, moved on to bluegrass; others like the Carlisles just kept playing their standards until they were discovered by a new generation in the 1960s and 1970s.

Alton and Rabon Delmore, however, changed their sound to fit the times. With the exception of a few "old timey" numbers like "Take it to the Captain," the tracks the Delmores made for Cincinnati-based King Records in the late 1940s are hard, gritty, modern music crafted for honky-tonk jukeboxes. The Delmores, like other honky-tonk artists, were catering to an audience of Southerners displaced by either the war or a search for better wages, who were now living in places like California or Chicago: people who, as Tony Russell wrote, "wanted a music that both reminded them of the old home and fit the faster culture of the new one."

"Boogie Woogie Baby" especially fits the bill. It's both an electric guitar boogie (with Jethro Burns on lead guitar) and a throwback to a string band breakdown, with the Delmores' close harmonies holding it all together. Recorded in Chicago on February 12, 1946; on Freight Train Boogie.

The bishop's diagnosis is ruthlessly candid. He notes as something new in history the rise of a large class of people who are quite insensitive to spiritual interests of any kind. They live a mediocre life, following a limited routine, taking their pleasures from the cinema, or the dog-track, and such intellectual stimulus as they need from the headlines of the secular Press. Their interest in politics does not extend beyond the issues which appear to affect wages.

These immense populations are the unresisting product of a machine age, and it is going to be uncommonly hard to get through to them any thought or aspiration which might become a hunger for God.

Summary of article by Dr. Hunter, Bishop of Sheffield, UK, Christian News-Letter, 1946.

The career of the trumpeter Henry "Red" Allen is the history of 20th Century black music in miniature. Allen, born in Algiers, Louisiana, in 1908, played as a boy in a marching band; he was a hot jazz player in the 1920s, playing on riverboats and with the likes of King Oliver; in the '30s, he was in Fletcher Henderson's big band, working with Henderson and Coleman Hawkins to create swing. And by 1946, Allen had reinvented himself again, working with both the new generation of bebop players as well as crafting some of the founding documents of rhythm & blues.

An example of the latter is "Get the Mop," where it sounds like the whole band has freely indulged in some benzedrine before recording it. Driving the track is Allan Burroughs, whose frenetic drumming galvanizes the rest of the players, while Allen provides a typically joyous, concise solo. The barely-there lyrics are a long way from Lorenz Hart, true, but the track' s intensity, speed and emphasis on the almighty beat marks it as the precursor to a good deal of music made in the latter half of the century.

In 1949, Johnnie Lee Wills, Bob Wills' brother, had a country hit with a track called "Rag Mop," which Wills allegedly composed along with his steel guitarist, Deacon Anderson. However, when Red Allen's publishers heard "Rag Mop," and realized that it was a complete rip-off of "Get the Mop," their lawyers got to work.

Recorded in New York on January 14, 1946, with Don Stovall (alto sax), J.C. Higginbotham (tb), William Thompson (p) and Clarence Moton (b). Find on That's All Right.

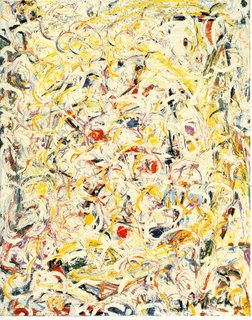

Pollock, Shimmering Substance.

Big Joe Turner, the full embodiment of R&B, also came out of the jazz world, in this case the rough and tumble Kansas City scene. Born in Kansas City in 1911, Turner earned his rep singing with groups like the Count Basie Orchestra and Duke Ellington's revues--by the late '30s, he was known as the greatest of the blues shouters.

"My Gal's a Jockey" was recorded during a slight ebbing of Turner's popularity, when he was recording for National Records in the mid-'40s and getting few hits. That said, "My Gal's a Jockey," when unleashed upon an unsuspecting public, became a national smash. It was a glorious full-bodied dirty blues suitable for dancing. Even in today's sex-saturated pop music industry, lines like "I've got a gal/she rides me night and day" still seem bluntly outrageous. Turner was shameless, and wonderfully so.

Recorded with Bill Moore's Lucky Seven Band in Los Angeles, on January 23, 1946. Find on Shout, Rattle and Roll.

summer on Bikini Atoll

In our time, political speech and writing are largely the defense of the indefensible. Things like the continuance of British rule in India, the Russian purges and deportations, the dropping of the atom bomb on Japan, can indeed be defended but only by arguments which are too brutal for most people to face, and which do not square with the professed aims of political parties.

Thus political language has to consist largely of euphemism, question-begging and sheer cloudy vagueness. Defenseless villages are bombarded from the air, the cattle machine-gunned, the huts set on fire with incendiary bullets: this is called pacification. Millions of peasants are robbed of their farms and sent trudging along the roads with no more than they can carry: this is called transfer of population or rectification of frontiers. People are imprisoned for years without trial, are shot in the back of the neck or sent to die of scurvy in Arctic lumber camps: this is called elimination of unreliable elements.

George Orwell, "Politics and the English Language," Horizon, April 1946.

The pianist Moon Mullican, born in Corrigan, Texas, in 1929, was as fluent in jazz as he was with hillbilly music. Born Aubrey Wilson Mullican (he got the nickname "Moon" either due to his premature baldness or his taste for moonshine), he started out playing piano in bars, and by the late 1930s he was working with Leon Selph's Blue Ridge Playboys and Cliff Bruner's Wanderers, both bands centered along the Texas Gulf Coast. He formed his own band, the Showboys, in 1943.

Mullican once called his style "East Texas Sock." As his friend Lou Wayne described it, "it is 2/4 rhythm with the accent on the second beat--and when we say accent we mean accent."

Sometime in October 1946, Mullican was in King Studios in Houston, listening to "Jole Blon," a record that the Cajun fiddler/singer Harry Choates recently had cut. Choates had revived a Cajun song from a generation before, first recorded in 1929 as "Ma Blonde Est Partie." Mullican, not knowing a word of French, let alone the Cajun patois, had no idea what the lyrics were, so he began riffing along, making up phrases on the spot and knotting them together (my favorite is the near-Dadaist "rice and gravy/filet gumbo/possum up a gum stump/comment ca va/cup 'o coffee/and Jole Blon").

The result was a track named "New Jole Blon" or "New Pretty Blonde," and which, when it was released by King in early 1947, became one of the top country hits of the year. Find on I'll Sail My Ship Alone.

I wrote this back in '04 about the French chanteuse Edith Piaf, a tiny summary that holds up all right, I think:

Piaf is the prism through which 20th Century French music is refracted--she grew up learning the chansons of the nightclubs, brothels and circuses, and, after she became a star, she gathered a host of disciples that would define the postwar years, including Yves Montand and Charles Aznavour.

Henri Contet and Marguerite Monnot's "C'est Pour Ça" is one of the most gorgeous songs Piaf ever performed, an ode to unrequited passion and the amorality of love, and whose opening lines pretty much say it all:

Il était une amoureuse

Qui vivait sans être heureuse

Son amant ne l'aimait pas

C'est drôle, mais c'était comme ça...

Recorded in Paris on October 7, 1946, with Les Compagnons de la Chanson. On 44 Original Recordings.

The years when Billie Holiday recorded primarily for Decca, 1944 to 1950, produced some magnificent records, where Holiday's voice, which was at its most evocative, was matched by intricate arrangements; it is the era of Holiday as pop genius, rather than as a pure jazz singer.

Holiday had some trouble grappling with Leonard Bernstein's "Big Stuff," a meandering composition that he wrote for the ballet Fancy Free. She first attempted it in 1944, with unsatisfying results. But on a take she recorded in 1946, she mastered it. Listen to the way her voice sounds like a muted trumpet, to the way she turns each line into a new narrative, all the while escorted by sumptuous accompaniment.

Recorded in New York on March 13, 1946. With Joe Guy (tp) Joe Springer (p) Tiny Grimes (g) Billy Taylor (b) Kelly Martin (d). Find on Complete Decca Recordings.

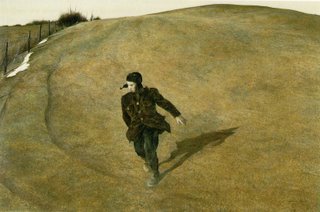

Wyeth, Winter 1946.

I first put up Peggy Lee's "I Don't Know Enough About You" back in the first 1946 set, which led to the very first comment I ever received for this blog. So for that happy memory, and to share a track which deserves far more recognition than it gets, here it is again for an encore.

"I Don't Know Enough About You" was the first song Peggy Lee and her husband, guitarist David Barbour, wrote together, and was one of her first solo successes after she left the Benny Goodman Orchestra. Under Goodman's strict reign, Lee had suffered--she was frequently ill, was forced to sing in the key of Goodman's earlier singer, Helen Forrest--but the endless touring and the barrage of music she had had to learn turned her from an ambitious North Dakota prodigy into, by 1946, a storied pop singer.

Here, she's in complete control of the lyric, and already has the lazy, sensual tone that would define later songs like "Fever" and "Black Coffee." The music is also quietier, smokier, than the typical big band number.

Released February 1, 1946, and it hit #7 on the pop charts. It was actually recorded three days before 1945 ended, but it sneaks under our usually strict chronological barriers simply because it's so damn good. On The Early Years.

The war has left visible traces here, too, and the damage has been substantial, but there is no lack of desire to rebuild. One day a road from Monterosso will meet the Bracco highway, near Pignone, and then perhaps an almost Castilian landscape will be lost. From the graffiti on the walls one might say that the era of Papirio Triglia is also a faded memory. I see shields crossed with the word Libertas [a symbol of the Christian Democratic Party], the hammer and sickle, even the insignia of the Paeveccu, a kind of separatist group.

Thus they appear, little altered but poised on the brink of enormous change: the five classic towns of the sciacchetra, the wine known to Boccacio as vernaccia di Corniglia...

Luckily, the fishing for anchovies, which this year has been stupendous, hasn't changed. And he who hasn't seen one of these boats return at dawn, half-submerged by eight hundred kilos of anchovies, its oarsmen seeming to plow the waves as they stand on the water, cannot say he is somehow familiar with the fishermen of the New Testament.

Eugenio Montale, article on the Cinque Terre, 27 October 1946.

Bebop, the new strain in jazz, had germinated during the war years--its seedbed was the after-hours sessions attended by swing band players, each trying to outplay the other. The solos got denser and faster, as they became tests of dexterity and endurance. The pace was breakneck, with players cracking melodies and chord progressions into shards, and fusing them into strange new shapes. Its greatest practitioner was a gentleman named Charlie Parker.

Dizzy Gillespie's "A Night in Tunisia" began as a standard swing number, a Latin-flavored ballad initially called "Interlude," which the young Sarah Vaughan performed in 1944. A year later, Gillespie had retitled the song and radically altered its structure, retaining only a taste of the old melody in the opening theme.

Parker recorded his take on "Tunisia" a month after Gillespie did, using a similar arrangement. All is fairly standard, until Parker's solo break (1:17 into the track) which is one of the most astonishing solos in jazz--a mere four measures, it is an unbroken string of sixteenth notes. Basically, Parker is playing twelve notes a second for five seconds, and making it sound effortless. After the first take, Parker turned to his sidemen and said, "I'll never play that break again." But Parker wound up having to do four more takes, each time doing a near-identical version of the four-bar break.

Recorded in Hollywood on March 28, 1946, with the neophyte Miles Davis (t), Lucky Thompson (tenor sax), Dodo Marmorosa (p), Arvin Garrison (g), Vic McMillan (b) and Roy Porter (d). On Complete Dial Sessions.

Mitsubishi factory, Nagasaki

The Bebop Boys was more a name than a group: it was bestowed upon a session of top young players who recorded a few tracks for Savoy in 1946. The Boys were essentially a bebop supergroup, featuring a number of players who would help define postwar jazz: the alto saxophonist Sonny Stitt, who was Bird's greatest disciple, the trumpeters Kenny Dorham and Fats Navarro, the pianist Bud Powell, tenor saxophonist Morris Lane (on leave from Lionel Hampton's band), baritone saxophonist Eddie de Verteuil (from Dizzy Gillespie's band), the bassist Al Hall and the drummer Kenny Clarke.

"Webb City" is Powell and arranger Gil Fulller's variation on Gershwin's "I Got Rhythm," whose chord sequence is the template for hundreds upon hundreds of jazz compositions. After the opening ensemble performs, the highlights are Powell, who at age 22 already sounds like a master, and Navarro, who shows in his pair of scorching solos just how much of a loss his premature death in 1950 was for jazz.

Recorded in New York on September 6, 1946, and released as a two-sided 78 (you can hear the fade in the middle of the track indicating when it was time to flip the disc). Find on the truly essential box set Bebop Spoken Here.

Baziotes, Green Form.

Floyd Tillman, born in Ryan, Oklahoma in 1914, was a songwriter and performer who was instrumental in creating both Western swing and honky tonk. Among his country standards are "It Makes No Difference Now," "Slipping Around," "They Took the Stars Out of Heaven," "Each Night at Nine" (a wartime weepie that Tokyo Rose allegedly had in heavy rotation to encourage soldiers to desert), "I Love You So Much It Hurts," and many others.

"Drivin' Nails in My Coffin," however, wasn't a Tillman composition, but rather was written by Texas songwriter Jerry Irby. It's a standard drinking song anchored by Tillman's low, intimate singing; traces of Tillman's vocal style can be heard in everyone from Johnny Cash to Willie Nelson.

Recorded in Hollywood on February 11, 1946, with Darold and Randall Raley on fiddles, Leo Raley (mandolin), Ralph Smith (p) and Lowell Frisby (b). On Best Of.

And as a coda, here's "Dodo's Bounce." The pianist/arranger Dodo Marmarosa had started out working with Gene Krupa and Tommy Dorsey, but by '46 he was working freelance on the West Coast (he's on the Parker track featured earlier) and was creating a smoother form of bebop that would evolve into the "cool" sound of the following decade. "Bounce," a duet between Marmarosa and the guitarist Barney Kessel, is a bop bagatelle whose modest charm lingers more than half a century after it was made. Recorded in Hollywood in late '46 for MacGregor Transcriptions. Also on Bebop Spoken Here.

No comments:

Post a Comment