1956:

James Brown, Hold My Baby's Hand.

The G-Clefs, Ka-Ding Dong.

Bob Landers, Cherokee Dance.

Howard Rumsey's Lighthouse All Stars, Love Me or Levey.

Lata Mangeshkar, Panchhi Banoon Udti Phiroon.

The Louvin Brothers, Let Her Go God Bless Her.

The Skylarks, Holili.

Tony Bennett, Just in Time.

Muddy Waters, Diamonds At Your Feet.

Rex Harrison, Why Can't the English?

The Modern Jazz Quartet (with Jimmy Giuffre), A Fugue for Music Inn.

Dmitri Shostakovich, String Quartet No. 6 in G Major, Moderato con molto.

In 1956, in Norfolk, Virginia, I had wandered into a bookstore and discovered issue one of the Evergreen Review, then an early forum for Beat sensibility. I was in the navy at the time, but I already knew people who would sit in circles on the deck and sing perfectly, in parts, all those early rock & roll songs, who played bongos and saxophones, who had felt honest grief when Bird and later Clifford Brown died.

By the time I got back to college…it looked as if the attitude of some literary folks toward the Beat generation was the same as that of certain officers on my ship toward Elvis Presley. They used to approach those among ship’s company who seemed likely sources—combed their hair like Elvis, for example. “What’s his message?” they’d interrogate anxiously. “What does he want?”

One year of those times was much like another. One of the most pernicious effects of the ‘50s was to convince the people growing up during them that it would last forever. Until John Kennedy, then perceived as a congressional upstart with a strange haircut, began to get some attention, there was a lot of aimlessness going around. While Eisenhower was in, there seemed no reason why it should all not just go on as it was.

Thomas Pynchon, introduction to Slow Learner.

"Hold My Baby's Hand" finds the Godfather of Soul present at the music's christening. James Brown needs no introduction: it suffices to say without Brown's influence, much of the popular music recorded in the last forty years is inconceivable.

Half a century ago, an A&R man named Ralph Bass was handed a demo recording by an employee in the Georgia office of Federal Records, a subsidiary of King. After listening to it, Bass sped to Macon, Georgia, and signed the demo performer, James Brown, for $200. The song was "Please Please Please" (which, according to legend, King's owner Syd Nathan called "the worst piece of crap I've ever heard in my life" but Bass recorded it anyway). It became Brown's first major hit.

The lesser-known but equally compelling "Hold My Baby's Hand" was two singles later, and it follows in the same groove as "Please Please Please". The building blocks of soul have been aligned by now: Brown's vocal is steeped in church singing, expressing both spiritual ecstasy and more temporal pleasures, while his impeccable sense of timing, and "his instinct for a dance pulse" (Dave Marsh) are already firmly in place.

Recorded on March 27, 1956 and released as the b-side of "No, No, No, No" as Federal 12277. On the out-of-print Roots of a Revolution and also, far cheaper, on iTunes.

Johns, Grey Alphabets.

As I've mentioned before, it was estimated that some 10,000 doo-wop records were made in the '50s. It was a rare period in pop music in which the doors were open to any callers. So you'd get a group of friends, find an sympathetic A&R man, record a single. If an independent label thought you had something, they'd grease the wheels at a local radio station and get the disc in rotation; if it showed signs of being a real hit, the indie would sell it to one of the majors. People you'd never met--DJs, label owners--would suddenly be identified as the composers of your song. Perhaps you'd get on Bandstand, maybe you'd get a slot on a national tour, playing 20 minutes a night. And then, after a few more singles flopped, the group would break up, and you'd all get jobs or go to college or join the army. So it went.

The G-Clefs were from Roxbury, a predominently African-American neighborhood of Boston. They were the four Scott brothers--Teddy, Chris, Tim, and Ilanga--and their neighbor, Ray Gibson. They started out in an actual street gang, holding a section of Roxbury turf, and evolved into a singing group. Like many doo-wop and soul groups, the Clefs first primarily sang at church until they realized that doing some R&B tunes was a good way to get paid, and meet girls.

"Ka-Ding Dong," one of the first national hits to come out of Boston, was recorded for Pilgrim Records in a quick session at Ace Studios, on Boylston St. (The guitar solo is by Boston teenager Fred Picariello, who would later be known as Freddy "Boom Boom" Cannon.) Because the band was from the North, their diction confused some audiences, who thought the G-Clefs were white. In 1957, the G-Clefs wound up cancelling a major tour of the South, unwilling to deal with the segregated restaurants and hotels they were forced to use.

"Ka-Ding Dong" was released in July 1956, and became a national hit over the fall. On Golden Age of American Rock & Roll Vol. 5.

I first heard Bob Landers' "Cherokee Dance" thanks to the Rev. Frost. To say it's one of the most exciting, fantastic rock & roll records ever made is an understatement. For those who missed it back when the Rev. first featured it, here you go.

Little information is available on Landers, who sang like Howlin' Wolf with a sore throat, or the mysterious Willie Joe Duncan, who played the unitar (essentially, a primitive one-stringed guitar, here electrified to great effect--another name for it was the "diddley bow"). Consider them rock & roll spectres, called into being to make this single, and then returned to dust. More info on the track from It's Great Shakes.

Released in March or April 1956 as Specialty 576; find on Rock N Roll Fever.

Any discussion of the novel nowadays soon strikes the pessimistic note. It is agreed, for instance, that there are among us no novelists of sufficient importance to act as touchstones for useful judgement. There is Faulkner, but...and there is Hemingway, but...And that completes the list of near-misses, the others, poor lost legions, all drowned in the culture's soft buzz and murmur.

We have embarked upon empire (Rome born again our heavy fate) without a Virgil in the crew, only tarnished silver writers in a bright uranium age...

In an odd way, our civlization has come full circle: from the Greek mysteries and plays to the printing press and the novel to television and plays again, the audience has returned to the play, and it is now clear that the novel, despite its glories, was only surrogate for the drama, which, confined till this era to theaters, was not generally accessible.

With television (ten new "live" plays a week; from such an awful abundance, a dramatic renaissance must come) the great audience now has the immediacy it has always craved, the picture which moves and talks, the story experienced, not reported...

Gore Vidal, "A Note on the Novel," New York Times Book Review, 5 August 1956.

Howard Rumsey began as a pianist, was a drummer for a while and at last became a bassist when a friend told him there was a shortage of bass players on the West Coast. Based in Los Angeles, Rumsey worked for Stan Kenton's big band until one night on the bandstand, when the two men argued until Kenton literally threw Rumsey off the stage.

Soon afterward Rumsey was walking around Hermosa Beach, a town south of Los Angeles, and spotted a large but empty bar called the Lighthouse Cafe. He convinced the owner to let him assemble a group to be the resident band, with the main requirement being their ability to play loud. The intention was to prop open the door, blast jazz at top volume and attract customers from the street. It worked--by 1954, the Lighthouse All-Stars were a main attraction. "They operate in a long, low, oblong, dimly lit room with an informal, easy atmosphere for shirt-sleeve jazz," as one reporter wrote.

Though Rumsey was a Californian by birth, he had little interest in the "cool" sound becoming popular there during the early '50s. Instead, he and his band played hard bop, which, to rehash one of my old definitions, is bebop played with more structure and more soul. A typical hard bop number had gospel and blues influences, a medium-tempo groove, and tight arrangements--even the drum solos had structure.

For the latter, take a listen to "Love Me or Levey," in which All-Stars drummer Stan Levey (an early bop drummer, who had worked with Gillespie and Parker in '45) adjudicates among the rest of the musicians, offering a response (sometimes for 32 bars) after each member of the group has had his say.

Recorded in Los Angeles on October 2, 1956, with Conte Candoli (t), Bob Cooper (tenor sax), Frank Rosolino (tb), Sonny Clark (p). Find on Music for Lighthousekeeping.

The Presleys on leave

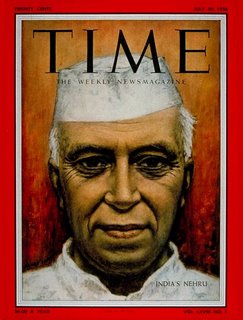

A decade or so after India became independent from British rule (and endured the bloody separation from Pakistan), its film industry, known generally as "Bollywood," was experiencing a golden age. Bollywood films were moving to color in the late '50s and had become extravagant productions, reflecting the optimism of the time.

Chori Chori, admittedly one of the few '50s Bollywood pictures I've seen, is pretty marvelous, a musical remake of It Happened One Night. It was the last film made together by the immensely popular stars Raj Kapoor and Nargis, which, to make a rough Western equivalent, would be as if Charlie Chaplin and Audrey Hepburn were a regular team.

The score, by Shankar-Jaikishan, is a delight, with most of the songs performed by the queen of playback singers Lata Mangeshkar. "Panchhi Banoon Udti Phiroon" is one of the lighter numbers, a georgic in which the melodies seem endless--there's a sense of imagination, optimism and beauty. While Kapoor is credited as the male lead singer, I believe it is more likely Mohammed Rafi (does anyone know)?

Watch the clip from Chori Chori here. You can find the song on iTunes.

The Louvin Brothers complete the trilogy of country music "brother" acts we've been showcasing. Where the Blue Sky Boys represented pure tradition as a working music, and the Delmore Brothers show the tradition bowing to a changing time, the Louvins represent the synthesis--while entranced with the old, weird songs of their and their parents' youth, the brothers were not mere re-enactors of the past, as their music was sharp, with no traces of false nostalgia.

Ira and Charlie Louvin were born under the name Loudermilk, which they changed around 1947 due to the public's general inability to spell or pronounce the name. The brothers grew up in Alabama, where Ira learned to play mandolin and taught his brother on guitar. One day the Louvins saw Roy Acuff’s huge touring car burning down the road (on the way to a show the Louvins could not afford admission to) and determined to make a career in country music.

After the brothers spent years playing the ragged edge of the southern touring circuit, and even splitting up a few times, such as when Charlie joined the army in 1945, they slowly began to get noticed, getting a name for themselves first as songwriters. By the mid'50s, they were recording for Capitol and were established country stars.

"Let Her Go God Bless Her" is the happy alternative to "Knoxville Girl," the ancient ballad the brothers covered on the same LP, Tragic Songs of Life. Where in "Knoxville Girl" the singer slaughters his girl when she wants to leave him, "Let Her Go" (a derivative of "St James Infirmary") is a resigned but jaunty farewell to a dying relationship, though there is a hint of doom in the last verse.

Recorded on May 2, 1956.

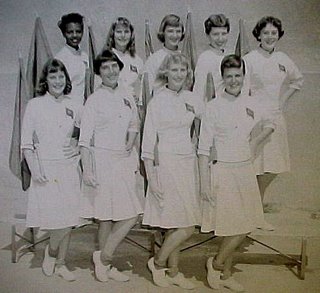

The Skylarks were a South African all-woman singing group from the mid-1950s that included the young singer Miriam Makeba as well as Abigail Kubeka, "Mummy Girl" Mketele, Mary Rabotapo and Nomunde Sihawu. Makeba, born in Johannesburg in 1932, began singing professionally with the Manhattan Brothers in the early 1950s. The Skylarks sang a sort of Xhosa jazz, '40s American-style swing mixed with traditional African harmonies, one fine example being "Holili."

In 1960, Makeba left South Africa, then in the depths of apartheid, and roamed as a woman without a country for three decades, her citizenship having been revoked by the South African government. At last in 1990, Nelson Mandela asked her to come home, where she resides today.

On the shamefully out-of-print Township Jazz N Jive, from which I've offered tracks before and will likely do so again.

Tony Bennett's "Just in Time"--the sound of the contented society. It's a recording as brightly lit as a Hollywood set, with Mitch Miller production, Percy Faith's orchestra impeccably recorded, and Bennett delivering a flawless vocal, all working in tandem to craft a Technicolor pop song, tailored to live forever on the radio, on records and, latterly, in dreams.

Recorded in New York on September 19, 1956 (it shockingly only placed #46 on the pop charts--I really had thought this one was a smash). Find on Essential Tony Bennett.

Rothko, Orange and Yellow.

Any real change implies the breakup of the world as one has always known it, the loss of all that gave one an identity, the end of safety...Yet it is only when a man is able, without bitterness or self-pity, to surrender a dream he has long cherished or a privilege he has long possessed that he is set free--he has set himself free--for higher dreams, for greater privileges. And remembering this, especially since I am a Negro, affords me almost my only means of understanding what is happening in the minds and hearts of white southerners today...

For the arguments with which the bulk of relatively articulate white southerners of good will have met the neccesity of desegregation have no value whatever as arguments, being almost entirely and helplessly dishonest when not, indeed, insane. After more than two hundred years in slavery and ninety years of quasi-freedom, it is hard to think very highly of William Faulkner's advice to "go slow."

James Baldwin, "Faulkner and Desegregation," Partisan Review, winter 1956.

Muddy Waters' "Diamonds At Your Feet" is a remake of a track he originally recorded for Alan Lomax in 1942, which had the more blunt title of "You Got to Take Sick and Die One of These Days." The original version was derived from some sung sermons Waters had heard--in his song, Waters is acting as a traveling preacher, coldly informing the world of its impending end.

"Diamonds At Your Feet" is an urban reworking, with electric guitar, a boogie beat and an altered lyric in which Muddy is now longing for the death of some poor woman, likely his demanding lover. When she dies, he's not just going to tramp the dirt down, but scatter diamonds on her grave.

Recorded on June 29, 1956, with Walter Horton on harmonica, either Jimmy Rogers or Pat Hare (g), Otis Spann (p), Willie Dixon (b), and Francis Clay (d). On the Anthology.

"Why Can't the English" is, of course, Prof. Henry Higgins' (as incarnated by Rex Harrison) lament on language from My Fair Lady, a lament which carries the slight utopian hope that if everyone would just speak in the Received Pronunciation, all would be well. Alan Jay Lerner's arch, dazzlingly clever lyrics, with their bouquet of rhymes, alliteration and effortless sense of sophistication, is the sort of lyric writing that by the mid-'50s, had become almost the exclusive property of the musical stage.

My Fair Lady premiered in New York on March 15, 1956. On the original cast recording.

The Modern Jazz Quartet began recording together in 1952, and, when at last they rested in the 1990s, they had made a body of work scarcely rivalled in jazz, let alone popular music. The core MJQ was Milt Jackson (vibes), John Lewis (piano), Connie Kay (drums) and Percy Heath (bass). It was a jazz institution that was also an oddity--a cooperative, where most jazz groups had a leader, and a group with no brass players in an era when the saxophone and trumpet ruled jazz.

The MJQ began slowly, its members more in demand as session musicians than in their quartet, but by the mid-'50s, things began to turn. Atlantic Records, which was looking to expand into LPs from its primarily singles-based business, signed the MJQ, with co-owner Neshui Ertegun becoming their producer and advocate.

"A Fugue for Music Inn" finds the MJQ with a rare collaborator, the clarinetest Jimmy Giuffre. The Music Inn was a resort near Lenox, Massachusetts, whose owners, as a hook to bring up tourists from New York or Boston, would hold "colloquia on jazz" during the summers. In 1956, the Inn asked the MJQ to be the resident ensemble, a situation that soon led to a jazz school being founded.

Lewis wrote "Fugue for Music Inn" as a fairly open-ended improvisational exercise, though most of the solos are traditional 12-bar blues variations. Giuffre's elegant, legato phrasing provides a fine counterpart to Milt Jackson's dance on vibes.

Recorded at "Music Inn", Lenox, MA, on August 28, 1956. On The Modern Jazz Quartet and Jimmy Giuffre.

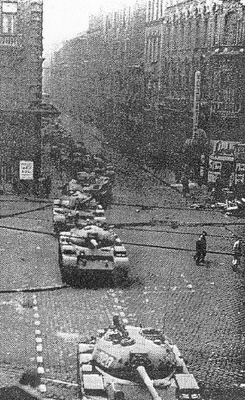

Hungary '56

The Russian composer Dmitri Shostakovich's fifteen string quartets, which span from the height of the Stalinist terror in 1935 to the detente days of 1974, are, for me, his core works, the private rebukes to his Party-approved public works, the quiet ruminations that parallel his symphonies.

This is the second movement, moderato con molto, from the Sixth Quartet in G Major, op. 101. There are three main themes that enter, one after the other--the first is carried by the first violin, the second (a gorgeous near-waltz) is borne by the cello and the third (which appears after the first theme's repeat) is a starker, "oriental" melody. Like dance partners, the three themes link and separate, weaving around each other, until the movement ends with sighs and a fading of the light.

The Sixth Quartet was premiered on October 7, 1956 by the Beethoven String Quartet in Leningrad (St. Petersburg). Here it is performed in a 1966 recording by the Borodin Quartet, the Russian quartet for whom Shostakovich wrote many of his string works. I'm not sure whether this Chandos CD contains the same performance (my version is from the multi-LP sets put out by Melodiya) but give it a shot. The Fitzwilliam Quartet's version is here.

No comments:

Post a Comment