1966:

Joel Grey, Wilkommen.

Albert Ayler, Our Prayer/Spirits Rejoice.

John Lennon, He Said He Said (She Said She Said).

The Other Half, Mr. Pharmacist.

France Gall, Les Sucettes.

The Walker Brothers, The Sun Ain't Gonna Shine Anymore.

Willie Bobo, Fried Neck Bones and Some Homefries.

Howard Tate, Ain't Nobody Home.

Bobby Lee Trammell, If You Ever Get It Once.

Loretta Lynn, You Ain't Woman Enough (To Take My Man).

Jackie Wilson, Whispers (Gettin' Louder).

Steve Reich, Come Out.

Hopeton Lewis, Take It Easy.

The Four Tops, Standing in the Shadows of Love.

Merle Haggard and the Strangers, I'm A Lonesome Fugitive.

Bob Dylan and the Hawks, Like a Rolling Stone (live, Royal Albert Hall).

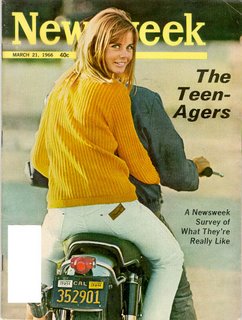

Luminaries come and go faster than a speeding bullet. Fads and fashions flame up and burn out in a week. The last six years have been so filled with places, people, and things you have forgotten about that this seems a good time to call for a halt. We have had enough! Enough!

And so we benevolently announce that the Sixties are over. Let six years be a decade. Let the next four be a vacation.

David Newman and Robert Benton, Esquire, August 1966.

"The 1960s," the most self-mythical decade of the 20th Century, seems impossible to reduce to a mere dozen or so songs. (And I love a great deal of the music of the period, despite the fact that, as someone born just after the whole shebang expired, I have, for much of my life, endured the previous generation's endless fascination with itself. My favorite example is the time, during an argument on a message board years ago, when a self-described Boomer said something like, "Your generation has piercings. Ours had peer-sings.")

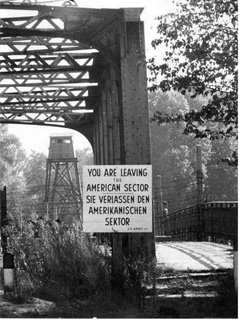

Anyhow, 1966 is the decade's hub--as Peter Fonda's corrupted ex-hippie character says in Soderbergh's The Limey, talking to his troublingly young girlfriend about the lost decade: "It was just '66 and early '67. That's all there was."

So: Wilkommen. Bienvenue. Welcome.

Kander and Ebb's Cabaret is, as you likely know, set in Weimar Germany just before the Nazi takeover. The host of the cabaret in which the play is set is only known as the Emcee, performed on stage and in the 1972 film by Joel Grey. In "Wilkommen," the opening number of the play, the Emcee welcomes his audience to a spectacle that could sum up the '60s as well as it does Weimar--"So? Life is disappointing? Forget it--in here, life is beautiful. The girls are beautiful. Even the orchestra is beautiful!"

Ian Buruma, writing recently on Weimar, said of the Emcee: What is so brilliant and disturbing about Grey's act is its air of boundless cynicism. Nothing is real about his character. He is utterly without feeling...he trades in sexual innuendo but is sexless himself. He is a hollow man who knows that survival rests on people's worst instincts...

Cabaret premiered in New York on November 20, 1966. Find on original cast recording.

The saxophonist Albert Ayler, a hierophant of free jazz, and his brother, the trumpeter Don Ayler, came from Cleveland, and during the early 1960s served in the jazz avant-garde, mainly playing small clubs and recording LPs for the then-obscure label ESP. While Ayler's music seemed cacophonic to some listeners at the time (there is a legend that "jazz experts" told the BBC to erase a live Ayler recording because his music was so bad), Ayler disagreed: "We are trying to rejuvenate the old New Orleans feeling that music can be played collectively and with free form." The Aylers looked back, before Jelly Roll Morton and his tight arrangements, or Louis Armstrong's cult of the soloist, to a half-mythical music in which all players could solo simultaneously, while still conversing. Theirs was a volatile music, a kiln in which anything could be fused--ragtime melodies, anthems, prayers.

Gary Giddins, as usual, sums it up: "[Ayler] scared the hell out of people, yet radiated a wildly optimistic passion. The optimism was manic...he never found the acceptance here that he won in Europe—some folks figured he was putting everyone on, among them true believers who were mortified by his later au courant compromises. Yet even in flower-child mode, he carried a cello and howled at the moon; he was never cut out for the Fillmore."

Along with Jimi Hendrix's "Star Spangled Banner" from Woodstock in 1969, Ayler's pairing of two of his original themes--"Our Prayer" and "Spirits Rejoice"-- in a performance in Lörrach, Germany, toward the end of 1966 is the closest that a musical performance came to encapsulating the violence and chaos of the time. Ayler and Hendrix seem like shadowy reflections of each other--one world famous, the other a cult figure, but both veterans, both re-inventors of their instruments who had to leave the country to find their audiences, both dead prematurely in 1970.

"Our Prayer/Spirits Rejoice" begins with a funeral march and erupts into a bugle call to wake the dead--bits of "La Marseillaise" are in there, as well as "Maryland, My Maryland." It's one of my absolute favorite recordings--a sublime, beautiful, shattering work.

Recorded by South Western German Radio on November 7, 1966 with Michel Samson (v), William Folwell (b) and Beaver Harris (d). On the now out-of-print Lörrach, Paris 1966.

Ruscha, Standard Station.

I never intend to adjust myself to economic conditions that will take necessities from the many to give luxuries to the few and leave men by the thousands and millions smothering in an air-tight cage of poverty in the midst of an affluent society. I must honestly say to you that I never intend to adjust myself to the madness of militarism in the self-defeating effects of physical violence. For in a day when Sputniks and Geminis are dashing through outer space, and the guided ballistic missiles are causing highways of death through the stratosphere, no nation can ultimately win a war. It is no longer a choice between violence and non-violence. It is either non-violence or non-existence.

Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., speech at Illinois Wesleyan University, 10 February 1966.

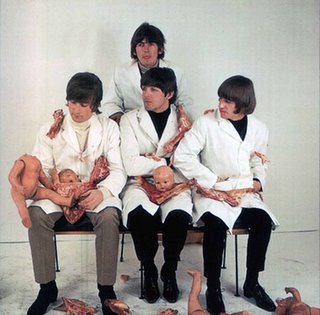

It is March, or April 1966: the man wandering through his Weybridge mansion doesn't really know. He sleepily shifts from room to room, occasionally stopping to pick up something left on the floor--a box with a winking electronic eye, a plastic monkey's head, a crayon drawing by his son, who he hears running a few rooms away.

Passing a window, he looks out onto the grounds, where a pair of gardeners are shearing a hedge. Is it dawn? Teatime? He's tired in any case. At last he finds the small walk-in closet that has become his workroom and sits on a stool, tuning his guitar absently. He steadies the tape recorder upon a stack of books, and turns it on.

A phrase has been in his head--the summer before, taking a break before Hollywood Bowl shows, the Beatles were hanging out in a rented mansion off Mulholland Drive. Peter Fonda had showed up with the Byrds, and after everyone but Paul had taken acid, Fonda was sitting on the couch talking nonsense. Something about the time he shot himself accidentally as a kid and his heart had stopped three separate times. "I know what it's like to be dead, man," said with the stoner's irritating conviction.

So John Lennon begins playing, the same chords again and again, trying to return the phrase to life. "He said...I know what it's like to be dead....I said.." What did I say back to him? Nothing. No, wait, 'Who put all that shit in your head?'. Fonda had lifted up his shirt then, to show his old wounds. A few more strums and then, gone. Tape machine off.

Lennon, happy to have a bit of a challenge, keeps working at it over the next few days. He tries changing the key; he slows it down; he stresses the first two syllables ("HE SAID...I know what it's like to be dead"). At some point, Lennon changes the pronoun--"she said" has more portent, a voice of someone who has gone beyond the veil, a high priestess of acid. Lennon drives on, at last filling in the first verse--B-flat to A-flat to E-flat, using his old rejoinder to Fonda, "Who put all that crap in your head?" And then, tape recorder off again, for good.

"I'd like to see a butterfly fit into a chrysalis case after it spreads its wings"

A few months later, one day in June, in fact the last day of the sessions for the Beatles' latest record, Lennon introduces the song as a last-minute addition. The band spends all day rehearsing it. The rhythm track requires three takes: Ringo in particular gives an inspired performance, echoing Harrison's lead guitar with some sharp kicks during the last line of the verse, and deftly handling the bridge with its unstable time structure, moving from 3/4 to 4/4 time apparently at a whim (much more info here). Then Lennon overdubs his lead vocal. The track is mixed, mastered, placed as the last song of Side 1 of an LP that ships in early August, just as Beatles records are being burned and stomped to pieces in the southern United States in reaction to Lennon's "bigger than Jesus" quote.

So a half-remembered phrase, a daydream sketch, now heads out into the world, to be consumed by untold millions, some of whom seek prophecies and clues in the spinning grooves that now contain the song.

The "She Said" demos have not been released officially, but can be found on bootlegs like Revolving. The official track, recorded in London on June 21, 1966, is on Revolver.

While some popular histories have it that until the British Invasion, American rock & roll was in the grave, that is not quite the case--in the early '60s, there was a strong local scene in nearly every decent-sized city, making incidental music for dances, hot rod races, beach parties and roller skate derbies. The main requirements were speed, loudness, an ability to learn new hits quickly and a strong, if sloppy beat. What the Beatles, and later the Stones and the Yardbirds, did was galvanize these garage bands to be more ambitious than they ever intended: in some cases, this meant performing letter-perfect imitations of British rock (the Knickerbockers' "Lies" being a prime example), or trying to reclaim the electrified American blues that the UK bands were playing, or just pretending to have taken drugs, or perhaps actually taking drugs.

“1966 was the year it all came together…out of the British beat, the folk scene, blues and everything else that was now on the table, a strange alchemy took place. A kind of pure garage rock emerged, snotty and arrogant, fueled by fuzz and frustration,” Greg Shaw.

“Mr. Pharmacist” was the first single released by a Los Angeles-based band called The Other Half. This track is a garage masterpiece, with a sneering punk vocal by Jeff Nowlen, blunt drug references and, of course, the required manic rave up--the middle section in which the band thrashes away as if on fire. (Lead guitar is by Randy Holden, who later joined Blue Cheer).

Of course, the garage spirit soon got corrupted and professionalized, so that a decade later, a new generation of amateurs would have to start all over again. The Fall, for example, laid claim to "Mr. Pharmacist" and turned it into one of their best-known tracks. The original was recorded in Los Angeles and released in September 1966 by GNP Crescendo. On Nuggets.

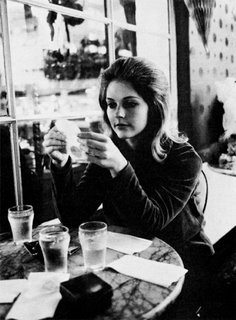

Godard filming Masculin-Feminin

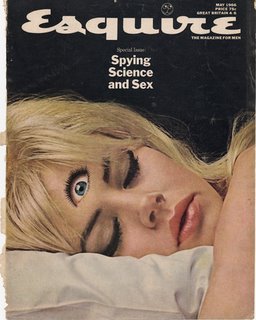

France Gall was a cute, blonde French moppet who was adopted by the songwriter/performer Serge Gainsbourg to be his vehicle to reach the teenage masses. The partnership worked wonders--Gall's version of Gainsbourg's "Poupée de Cire, Poupée de Son" won the 1965 Eurovision competition, while their collaboration on "Laisse Tomber Les Filles" created one of the finest pop singles of the decade.

However, unfortunately for Gall, her mentor was also a bit of a pervert. So in 1966, Gall received Gainsbourg's latest composition, a song ostensibly about a young girl's love for sucking lollipops, but whose lyrics, when listened to with even a hint of a dirty mind, appeared to be an unabashed ode to, well, something else:

While the creamy sugar

Flavored with anise

Sinks in Annie's throat,

She's in heaven.

Poor France didn't catch on, even when during the video for the track, she had to perform with dancing phalli and models deep-throating lollies. When she eventually found out, she was understandably angered and ended her partnership with Gainsbourg, who went on to whole new dimensions of sleaze.

That said, "Les Sucettes" is a marvelous piece of pop music whose pleasures ought not to be diminished by the sordidness of its origins. On Les Sucettes.

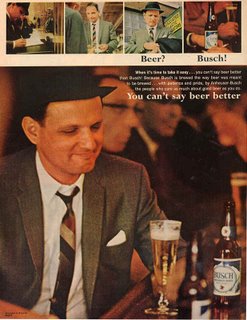

The producer Phil Spector once called his singles "little symphonies for the kids", and by 1966, this style of ornate, baroque studio pop--filled with booming drums, reverb all over the place, choirs, instruments stacked upon each other like folding chairs--was at its peak. (You could argue that the end of monophonic sound helped kill the style, as something like "Be My Baby" simply doesn't work in stereo).

The Walker Brothers, a trio founded in 1964, were actually not brothers, and were an American group whose greatest successes came in the UK. Indeed, for a brief moment after the Beatles stopped touring but before Sgt. Pepper was released, the Walker Brothers inherited their popularity, issuing a few colossal hit singles. The finest was their reworking of a flopped Frankie Valli track, "The Sun Ain't Gonna Shine Anymore," turning it into a Spector-esque pop cathedral of sound, anchored by lead singer Scott Walker's baritone.

Released in March 1966. On Portrait.

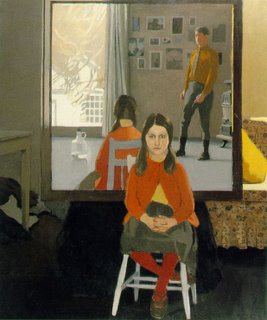

Porter, The Mirror.

Willie Bobo, born in Spanish Harlem in 1934, had become one of the top jazz and Latin percussionists by the late 1950s--his specialties were the congas and timbales. He worked with everyone from Tito Puente to the Cal Tjader Modern Mambo Quartet to Mary Lou Williams, who allegedly gave him the nickname "Bobo" (his real last name was Correa).

By the mid-'60s, Bobo was leading his own group and recording a number of LPs for Verve that offered a mix of Latin soul, boogaloo, mambo and salsa. A prime cut from his 1966 LP Uno, Dos, Tres was "Fried Neck Bones and Some Home Fries," a tune that Carlos Santana soon grabbed.

Recorded either on January 22 or April 25-26, 1966, with the percussionists Osvaldo Martinez (who provides the guiro), Victor Pantoja, Carlos "Patato" Valdez and Jose Manguel, while Bobby Brown is on multiple saxophones. On Willie Bobo's Finest Hour.

I like to think that 70 years ago, roughly the same number of spectators assembled in the Grand Café as are gathered here tonight. Our slight advantage is that at this moment, 10.35 in the evening, some 400 million others are doing exactly the same the world over. What are they doing, whether in aeroplanes, in front of television sets, in film societies or in the local cinemas? They are drinking words. They are fascinated by images. Like Alice in front of Cocteau’s beloved looking glass, they are, in other words, wonderstruck.

The cinema, in fact–-and hence, doubtless, its popular appeal–-is a little like the Third Estate: something which aspires to be everything. But let us not forget the film is nothing if it is not seen, in other words if it is never projected...

Here, too, in this neighborhood cinema, children come each Sunday to match their youth against that of the cinema’s masterpieces. And were Proust to happen by, he would have no difficulty in recognizing Albertine and Gilberte in the young girls sprawling in the front row, thus adding a new chapter to Time Regained.

Jean-Luc Godard, speech at the Louis Lumière Retrospective, Cinémathèque Française, 12 January 1966.

Howard Tate, a soul singer in whose '60s records “the basic Al Green vocal concept arrived about three years early” (Dave Marsh), was born in Macon, Georgia, in 1939. In classic soul fashion, Tate began as a church singer, working with Garnet Mimms in a gospel group, and was singing R&B by the early '60s. Mimms introduced Tate to Jerry Ragovoy, who signed Tate for Verve Records and set him up with some of New York's top session musicians, including Paul Griffin and Chuck Rainey.

One of the first results was the fantastic single “Ain’t Nobody Home,” written by Ragovoy and Mort Shuman. It is soul at a bedrock level, with Tate knowing exactly when to push and when to ride the groove, while spicing the track with falsetto leaps.

Recorded in New York on April 22, 1966. On the out-of-print Get It While You Can. Howard Tate is still touring.

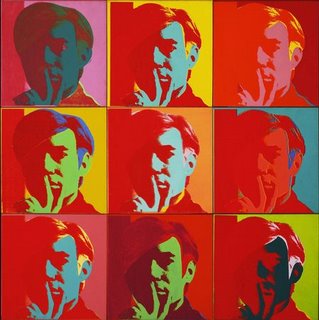

Warhol, Self Portrait.

Bobby Lee Trammell, born in Arkansas in 1940, was a rockabilly maniac with a bad streak of luck. In 1956, after Carl Perkins listened to him sing, Trammell headed to Memphis to see Sam Phillips, who judged that the kid was too raw and who told him to keep rehearsing. Unwilling to wait, Trammell went to California, where he managed to record a few singles. Rick Nelson loved the first, "Shirley Lee," but Trammell turned Nelson down when Rick asked him if he had any new compositions. Trammell also continually got in trouble with concert promoters for inciting his audiences to riot.

By the mid-1960s, still looking for his break, Trammell was billing himself as "the First American Beatle," and recording a number of singles for tiny labels like Sims and Alley. For the latter, sometime in 1966, Trammell offered a burst of pure, wild rock & roll called "If You Ever Get It Once," in which the old Sun Records spirit suddenly reappeared. The single went nowhere, unfortunately, but Trammell kept on the road. When he at last retired in the 1990s, Trammell wound up serving for a few years in the Arkansas House of Representatives.

On Arkansas Twist.

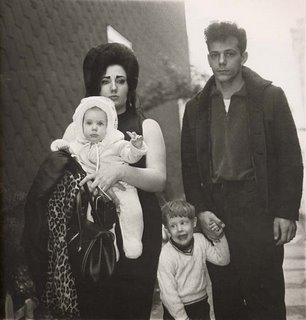

Arbus, A Young Brooklyn family going on a Sunday outing.

Loretta Lynn, born in Butcher Hollow, Kentucky, in 1935, lived a life very much like a country song--see the film Coal Miner's Daughter for the details. The heir of Kitty Wells and Jean Shepard, Lynn, by the mid-'60s, had begun recording songs hilarious in their candor and blunt in their attitude toward the typical country subjects of drunkenness and adultery.

A typical Lynn heroine has no use for cheating husbands or, worse, their trashy mistresses--"You Ain't Woman Enough (to Take My Man)" is a fine example, sung by Lynn with grit and sass and enveloped in Owen Bradley's seamless Nashville Sound producton.

Released in September 1966. On You Ain't Woman Enough.

Jackie Wilson's "Whispers (Gettin' Louder)" is the start of a wave of great singles recorded by Wilson in the late 1960s, the finest perhaps being the ebullient "Higher and Higher." "Whispers" is an odd beast--its ominous tone and hints at paranoia are undercut by Wilson singing, with all seriousness, "Peaches!"

But forget the lyric. The core of this track, besides Wilson's typically phenomenal singing, is the fantastic rhythm section: Motown regulars Benny Benjamin and James Jamerson, delivering a propulsive groove that just slams the song home.

Recorded on August 8, 1966 and released in September; on Greatest Hits.

In 1964, a black youth named Daniel Hamm was arrested and convicted after the Harlem riots for a murder he didn't commit. Hamm had been beaten during the riot, but as the police were ignoring his pleas to be taken to the hospital, Hamm, to convince them, squeezed one of his bruises until he bled. In a tape recording made later, Hamm said, simply, "I had to, like, open the bruise up and let some of the bruise blood come out to show them."

Two years later, the composer Steve Reich, who had been commissioned for a benefit funding the retrial for the Harlem Six (as Hamm's group of defendants were known), went through ten hours worth of tapes related to the riots, testaments of defendants, police, mothers, witnesses. "Everyone you could imagine," Reich said later. "This one phrase seemed emblematic. The speech-melody is everything. It then generates all kinds of variations upon itself melodically and on the meaning of the word..."

Reich re-taped the fragment "come out to show them" on two channels. The channels quickly slip out of sync, echoing and reverberating, the voices splitting into four, then eight, becoming a canon of sorts, until the words become incomprehensible, human speech reduced to its most basic tones and rhythms, as though offering a sonic portrait of how an infant's mind learns speech.

On Early Works.

"Rocksteady" was a transitional phase of Jamaican music, serving as the vestibule between ska, the music of Jamaica's early independence years, and reggae. Where ska was harsh, with a demanding skanking rhythm, rocksteady was slower in tempo, with a more supple groove (the bass, for instance, moves from its old role of simply providing a bottom end towards becoming a lead instrument, hitting on the off-beat and anchoring the guitar). It was the music for a new generation of country kids filling up the Kingston slums--the rude boys.

Hopeton Lewis' first session with the producer Winston "Merritone" Blake resulted in this single, which reportedly sold 10,000 copies in a weekend. It's perhaps the quintessential rocksteady track, with minimal instrumentation (no horns, for example), an irresistable groove, a soulful vocal by Lewis and a lyric that dwells on nothing but the present.

On This is Reggae Music.

Daniel Ellsberg in South Vietnam, 1966

WELCOME KING OF KINGS

THE TEXAS BULL

THE WORLD MARSHALL

WE LIKE BIG SHOT OF THE WORLD

Handmade posters by South Vietnamese well-wishers, waved at Lyndon Johnson during his two-hour, 24-minute visit to South Vietnam, 17 October 1966.

The tiny Vietnamese, whose hips are no wider than a Texan's thigh, gazes up, always up, at the phenomenon, and somewhere behind his eyes there is wonder. He sees his little towns spread and shake with violent life…in places like Pleiku and Ankhe half a dozen saloons open up every week. Bar girls wiggle into town, dressed at midday as for midnight. It is rather like the set for one of the old style, clear-cut Westerns. You catch yourself expecting to see John Wayne ride in any moment.

Anthony Carthew, "Vietnam is like an Oriental Western," New York Times Magazine, 23 January 1966.

"Standing In the Shadows of Love" is the middle work of a trilogy of masterful pop records made by some core Motown players--the Four Tops and the production/songwriting team of Lamont Dozier, Brian Holland and Eddie Holland.

In 1966 and 1967 the Tops and Holland/Dozier/Holland made a series of psychological thrillers, in which lead singer Levi Stubbs seems to be staring into the abyss. The first, “Reach Out I’ll Be There," is ultimately redeemed by its message of friendship and hope, but its sequel, “Standing in the Shadows of Love," just slips into darkness. As the Tops themselves say, “it may come today, it might come tomorrow/but it's for sure I ain’t got nothin’ but sorrow.” The last of the trio, 1967’s "Bernadette," a masterpiece of betrayal and obsession, finds Stubbs going further into the labyrinth.

A typical Motown recording from its golden age, "Shadows"' production and arrangement are brilliant--listen to how the track is crafted to keep surprising the ear while also keeping you on the dance floor. James Jamerson's bass serves as a suspension bridge, Benny Benjamin offers drum salvos, and the Tops sing a fatalistic acceptance of despair, while the track is flavored with bits like the odd 'clip-clop' rhythm at the beginning, the bongos appearing out of nowhere during the middle eight, or the ominous flute high in the mix at certain moments.

Released November 28, 1966; on Ultimate Collection.

Friedlander, New York City.

Merle Haggard, born in Bakersfield, California, in 1937, grew up learning how to play music and be a thief. The latter ultimately got him sent to Folsom Prison, where he began to turn himself around. By 1962, he had begun recording with Tally Records, and a few years later, he had landed at Capitol, where he became, after Hank Williams, the most influential singer-songwriter in postwar country music.

Haggard, along with Buck Owens, is said to typify the "Bakersfield sound"--the rougher alternative to the smooth country-pop being crafted in Nashville. As with most things, there's some truth and some legend to the claim, as not all Nashville tracks were soft, while some of Haggard's material is as polished as country gets.

"I'm a Lonesome Fugitive," also known as "The Fugitive," is one of my favorite Haggard songs, masterfully sung and impeccably played. And "Mama used to pray my crops would fail" is probably the best country lyric ever written.

Recorded August 1, 1966 and released in November--it would become a #1 country hit. On The Lonesome Fugitive.

Marden, The Dylan Painting

In the early months of 1966, Bob Dylan spent much of his time befuddling and enraging his fans. In New York on an off week, he went on the radio to angrily belittle kids who were wondering why he wasn't singing protest songs anymore, and in the spring, he embarked upon a chaotic Australian/European tour.

By the time the tour hit the UK, in May 1966, the performances had become ritualized. The audience would sit absolutely reverent and silent during the first acoustic set, in which a stoned Dylan would trail through ten-minute renditions of songs (some, like "4th Time Around," yet to be released on LP). An intermission, and then Dylan would return with a group of Canadian rock & roll players and would be, at times, loudly booed, cursed, and harangued. The most infamous night came in Manchester, preserved on a set officially released a few years ago, when an outraged fan screamed "Judas!" between songs.

In retrospect, the whole situation seems bizarre, with both Dylan and his betrayed folkie fans starring in some improvised touring drama. Like a number of events in the '60s, it seemed a strange irruption of the medieval--a wild, unprovoked outpouring of spirit, like a sort of tarantism--into the modern world, but there was also the sense that everyone was putting on a show for television and the news magazines.

All we have left are the recordings.

This version of "Like a Rolling Stone" is the last tune of the penultimate performance of the tour, from the Royal Albert Hall on May 26, 1966. Dylan begins with something he had never done before--he introduces the band by name ("they're all poets," he adds.) Dylan keeps talking--he's obviously exhausted, possibly sick and near a nervous breakdown, offering just half-loops of thought: "If it comes out that way, it comes out that way." Or "This song here is dedicated to the Taj Mahal." At last, rallying himself, he thanks the crowd for its efforts, and kicks off.

This version of "Rolling Stone" has a weary majesty to it, a sense of climbing a mountain one last time. At times, it sounds like it may never end. But at last it does, and the band walks off. One last show, and Dylan would fly home, get in a motorcycle crash, retreat, regroup, and never quite make music like this again.

On bootlegs like The Genuine Royal Albert Hall Concerts.

No comments:

Post a Comment