1986:

Ivor Cutler, Roget.

The Mekons, Oblivion.

Pete Townshend, Save It For Later.

David and David, Swallowed By the Cracks.

Big Stick, Drag Racing.

John Carter, Moon Waltz.

Prince, Girls and Boys.

The Judds, Grandpa (Tell Me 'Bout the Good Old Days).

Robert Cray, I Guess I Showed Her.

Timex Social Club, Rumors.

Megadeth, Peace Sells.

Dwight Yoakam, Guitars, Cadillacs.

Les Mangelepa, Harare.

Elvis Costello, I Hope You're Happy Now.

The Smiths, The Boy With the Thorn In His Side.

Wynton Marsalis Quartet, Autumn Leaves.

Farley "Jackmaster" Funk and Jesse Saunders, Love Can't Turn Around.

John Adams, Short Ride in a Fast Machine.

Marley Marl with MC Shan, He Cuts So Fresh.

The Go-Betweens, The Ghost and the Black Hat.

Life used to be work until five o'clock and then you were meant to have some fun, some nourishment, some leisure. Americans don't understand leisure. They don't have a clue. They understand work; they understand play; they understand love; they do not understand leisure...

Is labor God? Is a job God? People vote like it is. Ronald Reagan is a vote to return to the company store. People look at that guy Nicholson down there yelling and say, "What's he do?" Nothing--he sits around and complains. At least a guy in a nice pin-stripe suit at down at the bank, he keeps the park clean, everything's cool. Who are these rabble-rousers? What do they do? Let's go back in there and let's buy shoes down at the conglomerate. Let's get our movie down at the conglomerate. Let's let the big guy in the pin-stripe suit run things, 'cause it will be quiet then.

Well, pal, that hasn't ever worked in the past. And it ain't gonna work in the future. Dream on, dream on. I can't do nothin' about it. I understand numbers. I'm going to reach fifty years old next year. I just turned forty-nine. There ain't time for me to turn this around...

If we're not a nation of idealists who fight against these things, I guess it's because we don't understand what it's costing us anymore.

Jack Nicholson, interview by Fred Schruers, Rolling Stone, August 1986.

Julia K. Swan, The Many Faces.

So here are the '80s, bright, loud, death-stippled, the unlamented lost years of my adolescence. As is typical, the music of time can't really be summed up in any comprehensible manner, so as my hero Ivor Cutler says, "I thought I'd ring the changes."

Punk, rock's aborted Reformation, never got a foothold in the United States, soon devolving into a secret language shared among a few scattered bands and converts. In the UK, where punk had played out on a much more public stage, its collapse was louder, messier and more ridiculous, as punk splintered into a dozen different factions, from Two-Tone (punk + ska) to"New Romantic" (punk + David Bowie + elaborate music videos.)

The Mekons were a leftist punk band from Leeds who had formed in 1977, their first single being "Never Been In a Riot," an answer record to the Clash's "White Riot," whose politics the Mekons viewed as inane and dangerous. They kept scratching away on the margins, and, while having periods of hibernation, survived longer than nearly all of their peers.

Revived by the Miners Strike of 1984-85, which proved to be Old Labour's Waterloo, the Mekons, having increased their ranks with refugees from The Rumour (drummer Steve Goulding), The Pretty Things (guitarist Dick Taylor) and The Damned (bassist Lu Edmonds), seemed to gain strength in desperation. As Milton, a huge Mekons fan, once wrote: "Joynd with me once, now misery hath joynd/In equal ruin: into what Pit thou seest/From what highth fall'n."

The band was now inspired by American golden-age country music, with songwriters Tom Greenhalgh and Jon Langford offering surrealist, apocalyptic cowboy songs, along with covers of "Lost Highway" and "Alone and Forsaken." The waltz "Oblivion," one of the best songs from this period, was also one of the first Mekons tracks sung by another key addition to the band, the inimitable Sally Timms.

Recorded in Leeds in March-April 1986; on The Edge of the World.

The incense burned away, and the stench began to rise...

Pete Townshend, the songwriter of his generation who had been most obsessed with youth, with its exploiters, its myths and its inevitable demise, had taken the advent of middle age the hardest. "Who Are You," the Who's last big hit, was about an encounter Townshend had with Steve Jones and Paul Cook of the Sex Pistols, at the end of which Townshend woke up hung over in a Soho doorway, rousted by a policeman.

During that night, Townshend had bemoaned his uselessness, had ceded the future to Cook and Jones, who in turn were baffled by him, as they had always loved the Who and didn't see what his problem was. (Had Townshend gone out drinking with John Lydon, it would've been another story). The night produced a self-lacerating song, Townshend yelling "who the fuck are you?" to the mirror, as well as snarling at the generation of punks vying for his throne; it is now best known as the theme song to the current decade's version of Quincy.

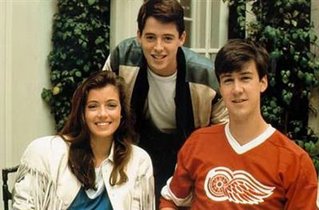

the punks meet the godfather

Townshend's decision to pull the plug on the Who in 1982 seemed to liberate him for a time. His solo records already had been stronger than Who LPs for at least a decade, and right before releasing the damp squib which was the Who's It's Hard, Townshend put out the weirdest thing he'd ever done, an album called All the Best Cowboys Have Chinese Eyes, filled with desultory songs about failure and age, all with rambling, somtimes unmoored lyrics. The finest track was "Slit Skirts," about how the singer and his woman no longer felt they could go out in their leather. "Can't pretend that growing old never hurts."

A few years later, Townshend was on stage at a charity gig in Brixton, and performed "Save it For Later," a recent hit from the Beat. Townshend sheared the song down to its skeleton, hanging the lyric on one repeated guitar figure. Singing in a harrowed but calm voice, Townshend lingers on the lyric's odd phrases (one of which for years I'd heard as "Black Karen Seven she's all rotten through"), infusing the line "your legs give way/you hit the ground" with weary resignation, and taking the lyric's silly sex joke and turning it into a vulnerable plea.

But soon afterward, he seemed to beat the retreat, heading back towards the past. He would spend over a decade endlessly reworking a failed rock opera he first attempted in 1970, and by the end of the '80s, Townshend would reunite the Who, keeping it going sporadically for another twenty years.

One night in the summer of 1993, during a concert near Boston in which he was promoting a terrible new record, Townshend began ranting at the audience, reeling off his recent accomplishments--like turning "Tommy" into a Broadway hit--with a mixture of obnoxious pride and self-loathing. "Don't you know, I've made so much fucking money," he screamed, to which some in the crowd cheered. Well, they had paid to see him, so perhaps they considered themselves shareholders.

Recorded in Brixton; on Deep End Live.

Goldsworthy, Sweet Chestnut Autumn Horn.

David and David were David Baerwald and David Ricketts, two songwriters who lived together in Los Angeles in the mid-'80s, often along with another songwriter, Ricketts' then-girlfriend Toni Childs. It wasn't the happiest of arrangements: Baerwald recalled that upon hearing Childs sing the line "Where's the ocean?" for the nth time, he went up to her and said "Take a right on Sunset." She never spoke to him again--soon enough, the David & David partnership ended.

[Ed. note--this summary is not entirely accurate, as Mr. Baerwald has noted in his comments (on the 1946 post)--DB and DR didn't live together, and they didn't 'shop around' their tape. "It just sort of happened," is a more accurate way of describing Boomtown's origins.]

The 1986 record Boomtown, which was the only thing David & David recorded, was essentially a professional remake of the demo tapes the two had been shopping around for years. "Swallowed By The Cracks," like their big hit "Welcome to the Boomtown," is an unsparing look at Los Angeles: its myths, its many snares, and the havoc they wreak on the talented, attractive kids who are served up on the altar, year after year. The singer is a failed choreographer, his friends a failed writer and actress--their season of hope seems short-lived, as before long they're working menial jobs or, in the singer's case, becoming "a drunken old whore."

Recorded in LA; on Boomtown. In the 1990s, Baerwald and Ricketts were part of a group of songwriters whose work would ultimately evolve into Sheryl Crow's first record, Tuesday Night Social Club. Both Ricketts and Baerwald, for example, are credited on Crow tracks like "Leaving Las Vegas."

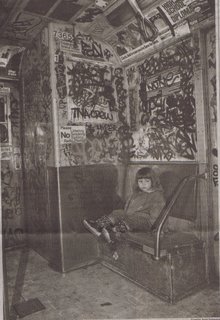

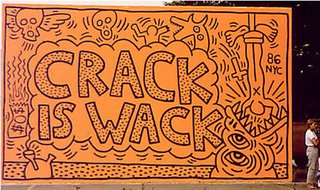

Big Stick is John Gill and Yanna Trance, one of the more fantastically abrasive groups to emerge from New York's underground rock scene in the '80s.

"Drag Racing," their first single (released initially on Recess and later on Blast First) consists of Trance saying "In the summer I wear my tube top, and Eddie takes me to the drag strip," interspersed with engines revving, vicious guitar noise, cheap drum machines, more noise, PA announcements, breaking glass, advertisements, mutters and come-ons. The record sounds like it was somehow fused out of melted surf and girl-group 45s.

You can find "Drag Racing" and other Big Stick tracks here.

The most ambitious jazz project of the decade was the clarinetist John Carter's five-album series, called "Roots and Folklore: Episodes in the Development of American Folk Music," an impressionist history of African-Americans from the great medieval African kingdoms to the rise of the slave trade, from transport to America to emancipation and relocation.

Carter, born in Fort Worth, Texas, in 1929, was a school music teacher well into his forties, when he finally decided to quit to play jazz professionally. He started out on saxophone, but by the mid-'70s had switched to the clarinet, an instrument which had fallen into disuse in jazz over the past few decades.

An avant-garde multi-album jazz series about the African diaspora would have been a tough sell at any time, but the '80s were perhaps the most unpromising era in recent memory that Carter could have tried it. Still, using several small, independent labels, he managed to record the series over eight years. Dauwhe is a portrait of the golden age of the African kingdoms, Castles of Ghana shows the arrival of the slavers and the corruption of the West African kings, Dance of the Love Ghosts is a study on the "middle passage" of African slaves to America, Fields depicts the lives of slaves in the ante-bellum South, and Shadows on a Wall is the story of the great Northern migration by blacks in the 20th Century. Carter died of lung cancer two years after making the last record.

Among Carter's regular collaborators for this series was the great bassist Fred Hopkins (formerly of Air, see the 1976 entry), Carter's longtime friend, the cornet player Bobby Bradford, the drummer Andrew Cyrille and former Mothers of Invention keyboardist Don Preston.

"Moon Waltz" is the end of the Dance of the Love Ghosts suite--described by Carter as follows:

So great was the despair of the passengers sailing from the castles [of Ghana, into slavery], it must have seemed on bright, star-filled nights that the moon danced in concert with their pulsating pain. The birth of the blues...

or as the Mekons would sing a few years later, in a verse about a slave ship crossing the Atlantic,

Down in the hull there is no sound

We're taking rock & roll to America...

Recorded in November 1986 in New York City; on Dance of the Love Ghosts.

Prince, at his peak in the '80s, was an unearthly combination of Miles Davis, James Brown and Jimi Hendrix, a talent so singular, whose feats seemed effortless, that his presence in pop music still seems a bit bewildering. Too willfully strange to remain on center stage for long, Prince had followed up his multi-platinum album and hit film Purple Rain with a swerve into religious psychedelia and in '86 made his second film, an odd venture called Under the Cherry Moon.

Yet the soundtrack to Cherry Moon was something else--a fantastic exercise in minimalist funk, a reworking of Sly Stone's Fresh set in some imagined Montmartre. The album's big hit, "Kiss," was built solely around Prince's vocal, a bare beat, a hint of synthesizer and some guitar breaks; "Girls and Boys" offers a slightly fuller palette--beats (from both the Linn drum machine and the Revolution's drummer Bobby Z.), the occasional honking line from a saxophone, chirps and quacks from synthesizers, a few guitar licks--and blossoms as it proceeds, with Prince delivering a loopily seductive vocal that becomes, at the track heats up, his first recorded rap.

On Parade.

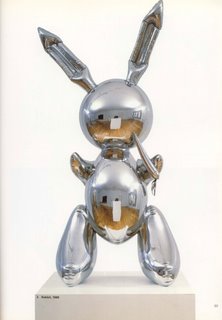

Koons, Rabbit.

In the '80s, in America, there seemed to be a general cultural yearning to return to, or, even better, somehow restore the poorly-remembered past, whether it was Michael J. Fox going back to the 1950s to mold his parents into more responsible people, or the various Stallone/Norris movies in which lone soldiers returned to 'Nam to settle scores.

The Judds, Naomi and Wynonna, updated the country music brother act for the '80s, offering in its place one of the first-ever mother/daughter teams. Naomi, born Diana Ellen Judd in Ashland, Kentucky, in 1946, married a marketing executive, moved to Los Angeles, and had two daughters. When the marriage fell apart in the early '70s, the Judds changed their names (except for Ashley, of course); Naomi became a registered nurse and supported the family while working on establishing her and Wynonna as a professional singing act. After sending out demo tapes for years, they at last got an audience with RCA execs, who signed them; the Judds began an astonishing run of 14 #1 country hits in less than a decade.

One of those hits, "Grandpa (Tell Me 'Bout the Good Old Days)" is on the surface part of the '80s nostalgia boom, an ode to the golden past when fidelity and stability were stronger than the present--it's sung by a child of divorce, asking her grandfather about a simpler time. Yet as David Cantwell wrote in his entry on this track in Heartaches By the Number: "In the end, [Wynonna] proclaims it all true--the faithful fathers, the kept promises, all of it. On the other hand, the mournful, home-bred harmonies she and her mother create sure don't sound very convinced." It's telling that grandpa never gets his chance to speak.

Recorded in Nashville; On Greatest Hits.

Marwood: Oh God, I don't feel good. Look, my thumbs have gone weird! I'm in the middle of a bloody overdose. Oh God. My heart's beating like a fucked clock! I feel dreadful, I feel really dreadful!

Withnail: So do I, so does everybody. Look at my tongue; it's wearing a yellow sock. Sit down for Christ's sake, what's the matter with you? Eat some sugar.

Robert Cray, born in Columbus, Georgia in 1953, was a major figure in the popular renaissance of the electric blues. Akin to the "new traditionalist" movement occurring in country music, this new generation of bluesmen, which also included Stevie Ray Vaughan, were interested in paring the blues back to its basics while also instilling a more modern sensibility to the lyrics and playing.

Cray began playing in the mid-'70s and made a few records on indie labels, including 1983's Bad Influence, a lean, nasty album that begins with Cray desperately trying to seduce a girl whose number he found etched in a phone booth. But his commercial breakthrough came in 1986 with Strong Persuader, a record saturated in infidelity, with Cray taking the part of the wronged husband, or an adulterer listening to his neighbors' relationship disintegrating on the other side of his apartment wall.

"I Guess I Showed Her" is a bit more light-hearted. Cray's narrator here is a bit of chump, trying to talk up his decision to leave his cheating wife and move into a fleapit hotel ("the hot plate's brand new"); already cuckolded, the singer seems unable to even act self-righteous about it. It's held together by Cray's needling rhythm playing, while the Memphis Horns add their sympathies.

Recorded in Los Angeles with Richard Cousins (b), Peter Boe (keyboards) and David Olson (d); on Strong Persuader.

In Nabokov's Lolita, Humbert Humbert tortures himself with images of his nymphet in the arms of 'kissy-faced brutes'; that's what Top Gun is full of. When Kelly McGillis is offscreen, the movie is a shiny homoerotic commercial. The pilots strut around the locker room, towels hanging precariously from their waists, and when they speak to each other they're head to head, as if to shout 'Sez you!' It's as if masculinity had been redefined as how a young man looks with his clothes half-off...

In between the bare-chested maneuvers, there's footage of ugly snub-nosed jets taking off, whooshing around in the sky, and landing while the soundtrack calls up Armageddon and the Second Coming--though what we're seeing is training exercises...

What is this commercial selling? It's just selling, because that's what the producers, Don Simpson and Jerry Bruckheimer, and the director, Tony (Make It Glow) Scott, know how to do. Selling is what they think moviemaking is about. Top Gun is a recruiting poster that isn't concerned with recruiting but with being a poster.

Pauline Kael, "Top Gun" review, The New Yorker, 16 June 1986.

The Timex Social Club were a group of high-school friends led by Marcus Thompson. In the summer of 1983, Thompson began writing a song he called "Rumors," which he showed to buddies Michael Marshall and Alex Hill. Thompson had only written the lyrics, so three tried to write accompanying music, at last finishing a four-track demo a few years later.

The demo wound up in the hands of producer Jay King, who brought the three into the studio. After some wrangling (King tried to put electric guitar into the mix, and thought he would also sing backup, both decisions proving to be dire ones), the track got professionally recorded and mixed, with Marshall singing lead. By the summer of '86, it had become a smash.

"Rumors" is a transition piece between the waning style of electro R&B and the rising tide of hip hop (it sounds a bit like a harder remake of Rockwell's "Somebody's Watching Me"), and also presages our current gossip-mad culture, though I don't think anyone back in '86 could have predicted something like US Weekly or Paris Hilton. Those were simpler times, in some respects.

Recorded January 3, 1986, in Richmond, California; on Hot R&B Hits.

I have to say it: I just don't enjoy heavy metal, mostly because of the poppy, dunder-headed brand of metal that was ubiquitous in the late '80s, to the point where it seemed like the culture at large was being punished for some crime it had committed.

That off my chest, let me add that I get a kick out of Megadeth's '80s records, perhaps because they're a contrast to the more-lauded Metallica, a band I've always hated. So here's the mighty "Peace Sells," the title track of Peace Sells...But Who's Buying, featuring Dave Mustaine and Chris Poland's dueling guitars, as well as David Ellefson's opening bass riff, used by MTV for years as the hook to its news broadcasts.

Released in November 1986; on Peace Sells...But Who's Buying?

Grandmother and grandaughter, Nicaragua, 1980s

Dwight Yoakam, born in Pikesville, Kentucky in 1956, found there was no room for him in Nashville, so he headed out to California in the early '80s. Refusing to play the countrypolitan hits of the era, and so having little luck with traditional country music clubs, Yoakam and his guitarist Pete Anderson wound up opening for the likes of Los Lobos, X and the Blasters.

Eventually, Yoakam found a home on country radio, incorporating rock & roll elements into his music (such as a heavier drum sound), while at the same time his purist's obsession with the symbols of classic country, his oft-proclaimed love of cowboy hats, beer drinkin' and honky tonks, helped make his music seem less radical.

"Guitars, Cadillacs," his second Top 10 country hit, sums up Yoakam's aesthetic, with the standard country fiddle countered by Anderson's jagged guitar licks, while Yoakam's tenor smooths it all out.

Recorded in LA; on Guitars, Cadillacs, Etc., Etc.

Les Mangelepa were among the many Congolese expatriate musicians who came to Kenya in the '70s and '80s, drawn by the many clubs and the recording studios, which were the best in East Africa. Les Mangelepa came to Nairobi in a mass exodus with other Zaire-based musicians, such as Baba Gaston and Nguashi Ntimbo; in fact, most of the group had originally worked for Gaston, until a number of them, including bandleader/guitarist Bwami "Captain" Walumona, Kasongo Wakanema, the singer-composers Evani Kabila Kabanze and Kalenga Nzaazi Vivi, Lutulu Kaniki Macky, and Twikale wa Twikale split to form Orchestra Les Mangelepa in the mid-'70s.

The band specialized in intricate harmonies, supported by multiple guitars and, a rarity among East African bands, a horn section. Unfortunately, at the peak of Les Mangelepa's career, they were deported by the Kenyan government in 1985, due to Kenya's increasingly restrictive work permit laws, and never quite regained their momentum.

"Harare," released @ 1986, is sung in Lingala, and its lyrics offer a traditional sad tale:

The girl who used to love me, today loves someone else. It's sad, who can I tell? You used me, showing me heavy love. Harare, I'm crying day and night but you don't listen to me, because you've got a new lover. I'm broken hearted. I'll never love again.

Recorded in Kenya; on the unfortunately out-of-print Guitar Paradise of East Africa.

Elvis Costello once called Blood and Chocolate, one of two records he released in 1986, "a pissed-off, 32-year-old divorcee's version of This Year's Model." A muddy, unrelentingly angry album, it remains an unsettling and bleak artifact some two decades on. At the time of its release, what disturbed my teenage self the most was the record's implication that the pains, betrayals and petty hatreds of adolescence would persist well into middle age; that there was no escape, just a further descent.

"I Hope You're Happy Now" is one of Costello's most bile-filled performances, a work of actual malice so incensed that Costello generally forgoes his usual wordplay, offering instead naked curses, like the cold verse towards song's end:

I knew then what I know now:

I never loved you anyhow.

Costello had attempted to record "I Hope You're Happy Now" several times in 1985 and 1986. The song may have been inspired by Dylan's "She's Your Lover Now," whose storyline is roughly the same: the singer, happy to be rid of a woman he's both obsessed with and who he utterly hates, gleefully watches her descend upon a new victim, who he is also jealous of. The released version has "a little bit more humor to it" than previous attempts, Costello would say years later. "It almost sounded like pop music."

Recorded in London by Costello and his estranged band, the Attractions: this would be their last collaboration for almost a decade. The track, like the rest of the record, was recorded essentially live, in one room, at stage volume, with instruments bleeding into each other in the recording; on Blood and Chocolate, a record so good it makes up for the past two decades of Costello's career.

In 1986, I was fourteen, which might be the very worst age in the world. So I'm grateful The Smiths were around at the same time.

While I haven't listened to the Smiths in ages, "The Boy With the Thorn in His Side," one of the band's many portraits of teenage martyrs, holds up well some twenty years later--it's glorious pop, driven by Johnny Marr's guitar and Morrissey's wryly overwrought singing. And if you've similar memories as me, sing along for the sake of the old, miserable days: "And when you want to live/how d'you start?/where d'you go?/who d'you need to know?" Unanswered questions, really.

On The Queen is Dead.

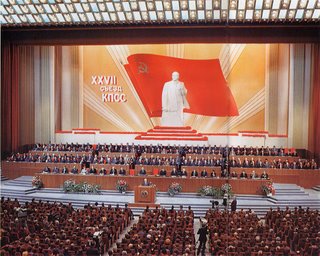

The USSR, in its closing performance

Ah, what to say about Wynton Marsalis? By far the most popular and most lauded jazz musician of his generation, he is perhaps more known for his controversial statements than his compositions, making him the first "top-tier" jazz player whose recorded legacy is a question mark. He's been recording for a quarter of a century, and one has to ask: where's his Kind of Blue? His Brilliant Corners? His "Weather Bird"? His "Koko"? His A Love Supreme? His "Black and Tan Fantasy"? His Shape of Jazz to Come?

While his talent is undeniable, Marsalis' greatest mark on jazz appears more symbolic: he, along with his brother Branford and a few other like-minded players, encased jazz in cultural prestige, turning the music, for better or worse, into what it is today--a well-funded adjunct of American classical music, performed impeccably and tastefully, and readied for the long haul.

(Marsalis also restored sartorial supremacy to jazz. Let me explain. For most of jazz's existence, its players were some of the coolest-dressed people on the planet. Here, watch Miles and Trane in 1959. But then in the '70s, it all went to hell--multi-colored capes, baggy pants, track suits, turtlenecks, etc. Look at poor Jack DeJohnette's boiler suit here. So thank Wynton for his efforts. )

Here is Marsalis' take on Johnny Mercer's "Autumn Leaves," from one of Marsalis' best live performances, his seventh engagement as bandleader at Washington DC's Blues Alley at the end of '86. Featuring one of Marsalis' most exciting quartets--Marcus Roberts (p), Robert Leslie Hurst III (b) and the fanstastic Jeff "Train" Watts (d). In these performances, Marsalis seemed to be channeling Kenny Dorham, and his seven choruses in "Autumn Leaves" offer "raring turnbacks and rugged riffs, notably a 10-bar incursion in the fourth go-round" (Giddins).

Recorded in Washington DC, either 19 or 20 December 1986; on Live At Blues Alley.

Welliver, Stumps and Ferns.

Farley "Jackmaster" Funk's version of Isaac Hayes' "I Can't Turn Around," a track called "Love Can't Turn Around" that featured an over-the-top vocal by Darryl Pandy, was the first house single to make the British pop charts, while remaining a relative obscurity in the U.S.

It was a prime example of Chicago house, a style that emerged from the collapse of disco in the early '80s, and was pioneered by a number of Chicago-based DJs, including Funk and Jesse Saunders, who collaborated on "Love Can't Turn Around." House was defined by its never-altering 4/4 electronic beats and its endless repeating basslines, a combination that can prove ecstatic on the dance floor and unbearable when blasted by an upstairs neighbor at 3 AM.

Originally released as a 12" single on DJ International, featuring a number of different mixes; on Trax Classix.

John Adams, born in Worcester, Massachusetts in 1947 to a musical family (both parents were in swing bands), began composing in the minimalist style pioneered by Steve Reich and Philip Glass, though by the 1980s he had expanded his pieces to include a wider variety of music, from operetta to Romanticism to pop.

"Short Ride in a Fast Machine" is one of Adams' most popular works, in part due to its pace and brevity--it's often used as a concert-ender. Composed in 1986 to celebrate the opening of the Great Woods Summer Festival, the piece is succession of chordal passages that dance over a steady beat pounded out on wood blocks.

This performance is conducted by Simon Rattle and performed by the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra; on Harmonielehre.

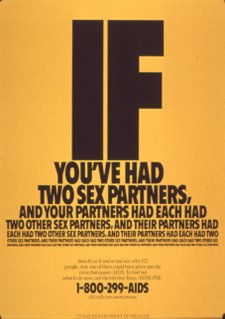

The '80s were, of course, hip hop's first full decade, in which rap began as a novelty and ended as the most politically and sonically ambitious genre of pop music. It was radically removed from the music of the past, often eschewing the verse-chorus-verse structure, vocal harmonies and even instruments, yet often directly fashioned from pieces of old records.

Marley Marl, born Marlon Williams in Queens in 1962, was one of rap's first star producers, working with everyone from Big Daddy Kane to Roxanne Shante to Eric B and Rakim, for whom he produced their first great singles, including "Eric B is President." Marl started out using synthesizers to generate his beats, but by the mid-'80s he was employing samples of funk and soul records to a far greater degree, especially in the records he produced for his cousin, MC Shan. "He Cuts So Fresh," for example, samples from Isaac Hayes' 1971 "Ike's Mood I/You've Lost That Lovin' Feelin'". It's a record that rocks harder than most alleged rock & roll records from the same era, offering a primer for listeners on the DJ's role in hip hop.

Released as an Uptown Records 12" single in '86; on Definitive Electro & Hip Hop Collection.

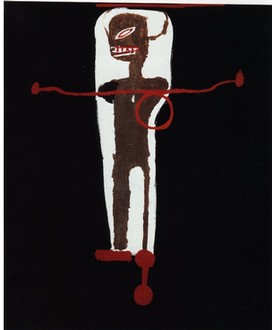

Basquiat, Gris-Gris.

Australia's The Go-Betweens, over time, have become my favorite band of the '80s, though I never listened to them at the time--I don't think many of their records were even available in the U.S. The songs of the late Grant McLennan and Robert Foster, brought into being with the help of drummer Lindy Morrison, bassist Robert Vickers and, later, oboeist Amanda Brown, have a subtle power, a quiet resonance. I've often found that a Go-Betweens song that did nothing for me on first listen is wandering in my head some days later.

McLennan died earlier this year: his songs, while often featuring rousing choruses and hummable melodies, had an acerbity to them, a sense of loss, of time's transience. "The Ghost and the Black Hat," a lesser-played track off the Go-Betweens' 1986 record Liberty Belle and the Black Diamond Express, is a case in point--it's an oblique death hymn, with railroads melting and dead husbands in the ground, all wrapped up in a shuffling, sprightly little melody.

Recorded in London; on Liberty Belle and the Black Diamond Express.

No comments:

Post a Comment