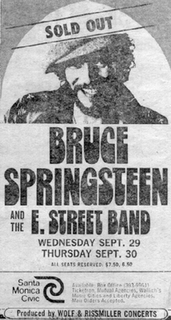

1976:

Dr. Buzzard's Original Savannah Band, Cherchez La Femme/Se Si Bon.<

Rare Pleasure, Let Me Down Easy.

James Talley, Are They Gonna Make Us Outlaws Again?

Eddie and the Hot Rods, Teenage Depression.

George Harrison, Crackerbox Palace.

Anthony Braxton, Cut 3.

Max Romeo, Sipple Out Deh.

Boz Scaggs, Lowdown.

The Wild Tchoupitoulas, Big Chief Got a Golden Crown.

Arlo Guthrie, Grocery Blues.

Michael Hurley and the Unholy Modal Rounders, Sweet Lucy.

Joan Armatrading, Down To Zero.

The Real Thing, You To Me Are Everything.

Blondie, X Offender.

The Ramones, Listen to My Heart.

Air, Midnight Sun.

I used to run into Warren from time to time during the 1970s. Once, at a nightclub called Reno Sweeney, we watched an entertainer named Genevieve White. This was just a few years after the Fillmore East had closed. Maybe Warren and I had thought the Fillmore, and all it represented, was going to be definitive for our generation, and here we were in a nightclub. Genevieve White had just sung a song called "Romance Is On the Rise."

"Romance is coming back, Warren," I said.

"You know what's coming back?" Warren said. "Everything. And then it's going away for good."

George W.S. Trow, Within the Context of No Context.

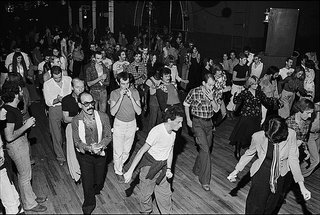

John Updike, of all people, wrote about disco in Rabbit Is Rich:

Peppy and gentle, the music reminds Rabbit of the music played on radios when he was in high school, "How High is the Moon," or "Puttin' on the Ritz": city music, not that country music of the Sixties that tried to take us back and make us better than we are. Black girls with tinny chiming voices chant nonsense words above a throbbing electrified beat, and he likes that...

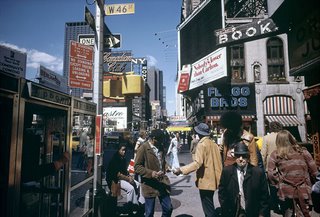

Disco was an urban music at a time when the white middle class was scrambling to get out of the decaying cities; it was a public, surface-obsessed music in an era of dedicated self-rumination. It was performed mainly by gays, women, blacks and Hispanics, in a period when the face of rock music was four or five white guys with bad hair; its emphasis on faceless performers in the hands of master producers upturned the Beatles/Dylan-inspired cult of the singer-sage.

"To me, the beauty of music is its possibilities for mutation," August Darnell, 1981.

August Darnell, born in Montreal in 1950, and his brother Sonny Browder Jr. grew up in the Bronx, and in the mid-'70s formed Dr. Buzzard's Original Savannah Band, in which Browder played guitar while Darnell played bass and sang backup--the pair collaborated on the songwriting. The two recruited Cory Daye, one of the most underrated singers of the era, drummer Mickey Sevilla and vibes player Andy Hernandez, who they chose after Hernandez scored highest on a questionnaire whose queries included "What is your political affiliation?" and "Do you consider yourself straight or a brat?"

In the depths of one of the most aesthetically vile decades in recorded history, the Original Savannah Band looked back to classic swankness, using Fred Astaire, Cab Calloway, Lena Horne, Myrna Loy, and Lambert, Hendricks and Ross as their role models. Their music sounded as if somewhere it was still New Year's Eve 1955 at the Copacabana, but it was playful and modern as well. "'Dr. Buzzard's' was the first release in many years to suggest that the pop-music past was not dead, an object of nostalgia or ridicule, but held untapped freedom" (Milo Miles).

The band landed a contract with RCA, which apparently had to drag their first LP out of them. The record looked as if it would be a flop until a few key DJs began playing it, and the gay community in particular took it to heart. The group went on to release a couple more sub-par records, and Darnell, Hernandez and Daye left to form Kid Creole and the Coconuts.

The Tommy Mottola "blowing his mind/on cheap grass and wine" was the band's manager, and, yes, the future ex-husband of Mariah Carey. Find here.

Rare Pleasure is disco at its most ecstatic and anonymous. The studio creation of a producer named David Jordan, Rare Pleasure released only one single for Cheri Records, "Let Me Down Easy," a track whose pleasures are boundless. It and hundreds of other discarded disco and funk records would provide the DNA for the music of century's end: in 1988, the one-note piano riff that leads off "Let Me Down Easy" would turn up in a house track by David Morales.

First heard this one on Lee Caulfield's wonderful site. On Disco Spectrum 1.

After losing the presidency, Gerald Ford returned to his old lounge combo

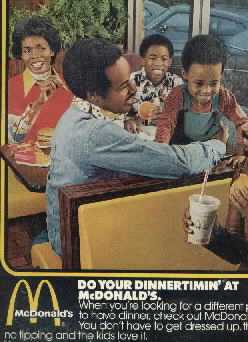

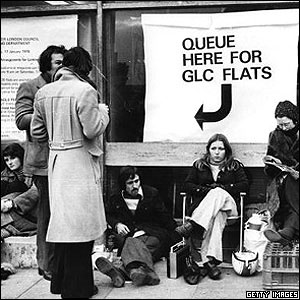

By 1976, the economic expansion that had defined the postwar years in the West had hit a wall. The many miseries of the period are perhaps remembered now in Time magazine shorthand-- gas shortages, vicious inflation and rate hikes (the prime interest rate in early 1970 was 8%--by '79 it was 16%), and governments generally bankrupt, corrupt or both. It was also the beginning of what would become a three-decade outsourcing of manufacturing jobs in the United States to, ultimately, countries in which factory labor was a slightly better alternative to the gulag.

Country musicians were among the first to take notice--for example, take Merle Haggard's "If We Make It Through December," released just before the OPEC crisis in 1973. Throughout the rest of the decade, the fears, disbelief, stoicism and anger of the working class, many of whom felt that whatever gains they had made since the war were being washed away, were expressed mainly via Nashville, though only on occasion, as most mainstream country songs stayed far away from the grim facts on the ground.

James Talley, born in Tulsa in 1943, was a carpenter and social worker whose biggest heroes were B.B. King, Bob Wills and Woody Guthrie. He began recording for Capitol, starting in 1975 with the marvelous album Got No Bread, No Milk, No Money But We Sure Got a Lot of Love. Talley never broke into the country mainstream, in part due to his barbed, often political songwriting, but he soon found a cult audience that included the governor of Georgia. When Jimmy Carter was elected president, he invited Talley to perform at the inaugural ball. Yet a year later, Talley was without a record contract and eventually left music for a while to get into real estate.

"Are They Gonna Make Us Outlaws Again?" from 1976's Tryin' Like the Devil, is one of Talley's best tracks, in which Talley contrasts the popular memory of the 1930s with the malaise of the current decade, and wonders where the outrage went. And then there's the last verse, which Woody Guthrie would have been happy to write:

Now there's always been a bottom, and there's always been a top,

And someone took the orders and someone called the shots.

And someone took the beatin', Lord, and someone got the prize,

Well, that may be the way it's been, but that don't mean it's right.

Recorded in Nashville; on Tryin' Like the Devil which can be found on Talley's website. Thanks to David Cantwell for assistance in getting this track.

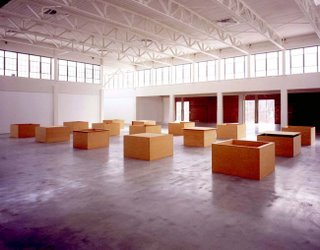

Judd, Untitled.

In pubs in North London and Essex, UK, during the mid-'70s, a group of young bands, bored senseless by the music of the day, began reviving soul and R&B songs from the previous decade. Like all reactionary movements, it was based on a general belief that the past held greater prospects than the dreary present, and out of the pub rock movement came much of what ultimately mutated into punk.

Eddie and the Hot Rods, from Southend-on-Sea, played sharp, fast rock & roll and R&B. Eddie was actually a dummy propped up on stage during early gigs--the actual players were Barrie Masters (vocals), Dave Higgs (guitar), Steve Nicol (drums), and Paul Gray (bass). The band became known for its amphetamine-speed covers of everything from "96 Tears" to Bob Seger's "Get Out of Denver."

Signed by Island Records, the band headlined at the Marquee in London in 1976, with the Sex Pistols as their opening band. Even punk dogmatists admitted that while the band had little to do with the punk ethos, the Hot Rods' live show was often untoppable.

"Teenage Depression," an update on Eddie Cochran's "Summertime Blues," is their finest moment. Released in October 1976; on Teenage Depression.

The Beatles, symbolically breaking up at the dawn of the 1970s, spent the rest of the decade showing their fallibility. Lennon paraded through a series of "eras," as if auditioning for his future biographers, undergoing primal scream therapy, going Maoist, getting drunk and recording old rock & roll songs, and at last going into semi-public exile until a lunatic shot him. Ringo just kept on being Ringo. McCartney carefully maintained his hold on the top of the charts, writing "pop for potheads," as Robert Christgau once said, and formed a pseudo-Beatles sequel band, minus any creative rivals and with his wife now installed onstage.

But what of George Harrison? Neglected as a songwriter during his time with the Beatles (although by the end of the '60s, his shelved songs were often better then the stuff Lennon and McCartney were offering), and having considered leaving the group as early as 1966, the Seventies should have been his for the taking. But after the 3-LP Grand Statement that was All Things Must Pass, Harrison seemed to peter out.

There were a number of reasons--his voice, never the strongest, gave out during a tour; he was sued for ripping off the Chiffons*. But most of all Harrison, at some point, seemed to realize the game wasn't worth it. While still putting out a record every couple years to keep up his contracts, Harrison spent more of his time hanging out with Monty Python, serving as the prime inspiration behind The Rutles parody, which in its way was more truthful about the Beatles than their official Anthology TV series.

"Crackerbox Palace," an ode to table-rapping childhood mysteries, is one of the best Harrison tracks from the late '70s. In typical fashion, Harrison sings about the Lord soon after quoting from a sex joke in Blazing Saddles. Also, this track goes in for personal reasons-- watching the video for this song (which I think aired on Saturday Night Live) stands out in the gauzy whirl of my childhood memories.

On Thirty Three and 1/3.

For jazz, the years after the death of John Coltrane in 1967 were some of the grimmest in the music's history. The black popular audience had already been turning away from jazz in favor of soul and R&B, and now the music's last main bastion of support--professionals, college kids and hipsters of all sorts--began deserting jazz as well. Many of its titanic figures were dying (Bud Powell in 1966, Coleman Hawkins in 1969, Ayler in 1970, Louis Armstrong in 1971, Ellington in 1974) and the future of jazz seemed either to be a move completely into wild, atonal free-form music or a hard, traditionalist swing back to standards, even Dixieland.

Miles Davis, sui generis as always, found a way out of the trap by making a string of electric jazz-funk records which were so ahead of their time they're still being absorbed today. In his wake, however, came the great "fusion" compromise, in which talented players dutifully performed improvisational takes on current hits like"So Far Away" or "You've Got a Friend." It was the beginning of jazz's current incarnation in the popular imagination as a sort of upscale mood music, as a cheap signifier of class and sophistication (take the cover of this hit 1980 LP by Grover Washington Jr., with its glass of chablis tastefully complementing the gold tones of the saxophone)

Some, however, headed out into the wilderness and returned with a new direction. Anthony Braxton, born in Chicago in 1945, was a former chess hustler and a multi-instrumentalist (he plays anything from the contrabass clarinet to the sopranino saxophone) who was among the many musicians affiliated with the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM), a Chicago-based group whose intent was to provide structure and support to a new generation of jazz players, and to encourage experimentation in all its forms, to push for a type of free jazz in which all options were open to players, even the choice to be as restrained as possible.

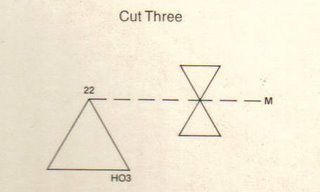

By 1976, Braxton was poised to be the avant-garde's breakout star. Where most of his contemporaries were recording for obscure European labels, Braxton signed with Arista, which gave him the budget to hire for the first time a large ensemble. "Cut Three" is the third track on side 1 of Braxton's first Arista LP, Creative Orchestra Music 1976. The official title, according to the LP sleeve, is the following bit of geometry:

Cut Three, as Francis Davis described it, is "a Midwestern circus march," complete with honking tubas and a glockenspiel. For a minute or so, all seems well--it's the sort of rousing march a band would perform on a village green or beer garden somewhere. Then, as much of the ensemble gets stuck playing an oompah figure over and over, three abrasive soloists emerge--the trumpeter Leo Smith "playing only those trumpet tones of no use in a march" (Giddins), the trombonist George Lewis and at last Braxton himself on clarinet, buzzing around the players like a hornet. And suddenly, order is restored, the sun comes out, the band marches off.

Recorded in New York in February 1976; on Creative Orchestra Music 1976, which was released briefly on CD in the '90s but can only be had for ridiculous sums today. The LP is pretty easy to find on Ebay, as I can attest.

Why do people go to movies like Jaws, The Exorcist or Ilsa, She-Wolf of the SS? So they can get beaten over the head with baseball bats, have their nerves wrenched while electrodes are being stapled to their spines, and be generally brutalized once every fifteen minutes or so (the time between the face falling out of the bottom of the sunk boat and the guy's bit-off leg hitting the bottom of the ocean). That is what today, is commonly understood as entertainment, as fun, as art even! So they've got a lot of nerve landing on Lou [Reed] for Metal Machine Music. At least here there' s no fifteen minutes of bullshit padding between brutalizations. Anybody who got off on The Exorcist should like this record. It's certainly far more moral a product.

Lester Bangs, "The Greatest Album Ever Made," Creem, March 1976.

Guston, The Pit.

Max Romeo, born in 1947 in St D'Acre, Jamaica, first got attention for lascivious tracks like "Wet Dream" (which Romeo once claimed was about a leaky roof, in a lame bid to appease British censors).

Yet by 1972, Romeo had begun writing doom-tinged songs, inspired in great part by the violent election battle between the JLP Party (which had run Jamaica since its independence) and the socialist, Rastafarian PNP Party, which Romeo supported. The PNP's victory in '72 presaged an even more chaotic, vicious fight for power in 1976.

This election, during which Jamaica descended into virtual civil war, produced some of the finest reggae singles of the era--Culture's "Two Sevens Clash," Junior Murvin's "Police and Thieves," Leroy Smart's "Ballistic Affair"--in which Rastafarian apocalyptic beliefs were infused with street-level reporting on the violence.

Romeo contributed as well, his finest track of the period being "Sipple Out Deh," a masterful Lee "Scratch" Perry production in which Romeo's vocals were supported by a colossus of tense rhythms. Romeo came to Perry with a lyric about how it was "dread out there," which Perry suggested should be changed to "sipple out deh" (it's slippery out there). This great Perry site marvelously describes the original mix: "Romeo's vocal sounds as if he's standing in a giant tin can, the backing vocals shimmer with ghostly echo, and the rhythm guitar sounds like a match being struck over and over again."

When Island Records head Chris Blackwell heard it, he gave Perry the go-ahead to record an entire album with Romeo. But the Island single version of "Sipple Out Deh" was retitled "War Ina Babylon," and the mix was altered dramatically, with Romeo's vocal recorded far more conventionally.

Recorded in Kingston; on War Ina Babylon (though I think that just has the remix, am not sure where "Sipple Out Deh" is).

Propaganda poster denouncing the Gang of Four

Boz Scaggs, born in Canton, Ohio, in 1944, had a musical career that could have doubled as a Rolling Stone-approved "history of rock": he started out at the University of Wisconsin, playing in rock & roll and blues bands with his friend Steve Miller, then went to London just in time for Beatlemania, then hit San Francisco at the peak of psychedelia. After catching the attention of Jann Wenner, Scaggs got signed to Atlantic and then Columbia, where he made a series of well-received but middling-selling rock/soul records.

But in '76, Scaggs broke through with an album perfectly poised for the times--a record of pure suggestion, rewarding its listeners' good taste, indulging in soul, disco, rock or ballads without committing to any of them. Silk Degrees is the '70s Los Angeles corporate sound at its peak, impeccably produced by Joe Wissert and performed by the studio mandarins who would soon form the group Toto. From it came a number of hits, including "We're All Alone" and "Georgia."

"Lowdown," however, is the album's highlight. The musicians, drummer Jeff Porcaro, bassist David Hungate, keyboardist David Paich and guitarist Fred Tackett, all wrote their own parts, then played live while Scaggs provided a guide vocal, nailing it in three takes. Hungate's rolling, snapping bass lines, the centerpiece of the song, were inspired by the Meters.

Recorded in Los Angeles; on Silk Degrees, one of those records that every household seemed to own in the late '70s, if my childhood was remotely typical.

The Mardi Gras Indians are a still-obscure American cultural institution. The Indians, who generally are black men from New Orleans' inner city neighborhoods, are the secret Mardi Gras tradition, a once-violent, exuberant parade that emerged when blacks were often unable to march in the mainstream Mardi Gras events early in the 20th Century. The association with American Indians--the leader of each "tribe" is called the Big Chief--was a tribute to the Indians' assistance to blacks escaping slavery.

The awesome Home of the Groove provided earlier this year a thumbnail sketch of the tribe known as the Wild Tchoupitoulas, who recorded an album for Island Records in 1976:

"George Landry, aka Big Chief Jolly of the Wild Tchoupitoulas from Uptown New Orleans, was the Neville brothers’ uncle and a big inspiration to them. Most of the tracks are his compositions, based on traditional Mardi Gras Indian songs and featuring their often cryptic chants combining words from various languages of their heritage. With a groove that’s guaranteed to make you move, [it] goes back to the days when African-American groups masking as Indians actually did injury-causing battle with each other as they’d meet on the streets Mardi Gras day. By the 1950’s, those conflicts had become ritualized competitions between “tribes” to see who could make and display the most elaborate, beautiful suits (costumes). But, in their songs you will still hear references to “gangs”, “the battleground”, “won't bow down”, “get the hell out the way”, and other confrontational subject matter...

Now, in post-diluvian New Orleans, this tradition may die out, as its neighborhoods have been destroyed."

The Wild Tchoupitoulas LP was recorded in New Orleans and produced by Allen Toussiant, with backing by the Meters, and support vocals by the Neville Brothers: in short, this is the essential New Orleans record of the past thirty years.

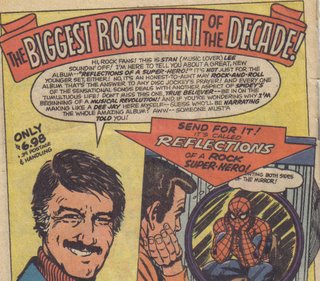

Without good software and an owner who understands programming, a hobby computer is wasted. Will quality software be written for the hobby market?

Almost a year ago [we] developed Altair BASIC...The feedback we have gotten from the hundreds of people who say they are using BASIC has all been positive. Two surprising things are apparent, however: 1) most of these "users" never bought BASIC (less than 10% of all Altair owners have bought BASIC), and 2) the amount of royalties we have received from sales to hobbyists makes the times spent on BASIC worth less than $2 an hour.

Why is this? As the majority of hobbyists must be aware, most of you steal your software. Hardware must be paid for, but software is something to share. Who cares if the people who worked on it get paid?...Most directly, the thing you do is theft.

I would appreciate letters from anyone who wants to pay up, or has a suggestion or comment. Nothing would please me more than being able to hire ten programmers and deluge the hobby market with good software.

Bill Gates, general partner of Micro-Soft, "open letter to computer hobbyists," 3 February 1976.

Oldenberg, Clothespin.

For whatever reason, I've never liked much of the folk music of the '60s, the mainstream stuff in particular--Baez, Judy Collins, Ian and Sylvia, Peter, Paul & Mary, etc. I know these records have a great deal of meaning to many people, especially those alive at the time, but there's perhaps a cultural barrier preventing me from enjoying them.

However, for what it's worth, I love much of what the folkies did in the '70s. Perhaps it's a sense that the spotless idealism has given way to a harder sense of reality, that some folks seemed to recover their senses of humor, that a growing realization that things were not working out to plan resulted in a heightened sharpness of observation. Joni Mitchell and John Prine's '70s masterpieces like Court and Spark or Sweet Revenge, for example, seem to embody this change.

Like all sons of famous fathers, Arlo Guthrie has mainly lived in his old man's shadow (was Jean Renoir the only one to escape this curse?). Yet Guthrie, who started out as the happy face of hippiedom, the gentle alternative to the histrionic likes of Jerry Rubin, made a number of fine, underrated records in the '70s in which he balanced protest songs (like "Victor Jara," an ode to the slain Chilean singer) with quieter human observations.

"Grocery Blues" is a goofy satire in which Arlo takes the kids down to the grocery store and finds that every act he makes, including keeping the freezer door open too long, now has a cost. At last, he grabs the kids and flees, declaring that "I don't mind no woman's lib/But if my woman don't want to go down to the store/the family isn't gonna eat no more."

On Amigo, one of his best records. Recorded in North Hollywood in June 1976.

"The '70s were low on glory and short on wonder. Utopian hopes that beguiled many of us for the century's first seven decades soured, curdled, became tarnished and generally turned ugly in the '70s. It became clear that what was looming on the horizon was not the city of gold but the river of shit." Peter Stampfel, 1991.

Peter Stampfel was a revivalist goof who was part of the '60s Village icons the Holy Modal Rounders and the Fugs. Jefferey Frederick was a rising folk singer who by the mid-'70s was heading the Clamtones, the best bar band in Portland, Oregon. Michael Hurley was a classic American eccentric, a sort of folk counterpart to Captain Beefheart.

For two days in a recording studio in Boston, the three men, who had worked with each other over the years, and a few other musicians came together to make a record called Have Moicy! Interviewed some twenty years later, Hurley seemed amazed by its power: "So many people have told me that they love it, it changed their life, it turned them on to old-time asskickin' hillbilly, it led them to a superior love life, it brought them much wealth and still remains a favorite after 20 years or 10. Everytime I listen to it, it sounds more together; it sounds like a bunch of loonies too."

A collection of tall tales, vignettes, and stomps, and populated by bank robbers, hash-smoking celebrants, barroom brawlers and talking newts, Have Moicy! is a record whose joys can't be described, only imbibed. Stampfel's yelping masterpieces like the teenage serenade "Griselda" sit alongside Hurley compositions like "Sweet Lucy" and "Driving Wheel", while the smooth, sardonic Frederick (who died far too young in 1997) offers tracks like "Robbin' Banks" ("you tell the teller thanks").

I couldn't choose just one, so enjoy Hurley's drunken travelogue "Sweet Lucy" and the truly essential "Jealous Daddy's Death Song," in which a dying man curses the guys who are going to bed his nubile wife as soon as he's in the grave, as sung by Modals' guitarist Paul Presti (with Stampfel on backing vox). A couplet from each:

I got on the phone, my mama spoke,

"Sorry son, but your mama's broke."

and

I know you can't wait until I'm dead

to try to drag her off to your waterbed

On Rounder's Have Moicy!.

Tanner's Jonah Who Will Be 25 in the Year 2000.

As time creeps onward at its petty pace, it seems that Joan Armatrading will be marked as one of the most influential musicians of her time. She was never a huge popular success, but her disciples--Tracy Chapman, Ray LaMontagne, India.Arie, etc.--have ruled in her name. Neo-folk radio stations (which are ever-popular up here in New England) simply ought to rename their format "the children of Joan Armatrading."

Armatrading, born in 1950 in St. Kitts but raised in Birmingham, UK, began making records in the early '70s, but her breakthrough was her self-titled 1976 record, from which "Down to Zero" is one of the best-known songs. Inspired in part, to my ears at least, by Van Morrison, it's a compelling track sung by Armatrading with command and dignity.

On Joan Armatrading; Armatrading's 2007 tour dates.

The Real Thing, the greatest Philadelphia Soul band to ever come out of the UK, had its origins in Liverpool. Lead singer Eddie Amoo's first gig was in 1962, serving as an interim act between Beatles sets at the Cavern. Amoo was in a doo-wop R&B group called the Chants, which, like most other black UK acts, was often recorded and marketed as if they were a white pop band, which proved frustrating and meant the Chants never had any decent material. By the early '70s, the Chants were mainly playing cabarets.

The British songwriter Ken Gold, who loved soul music, had been frustrated in his attempts to find any UK acts willing or able to perform his R&B and soul material, so at last he went to the U.S., placing songs with Aretha Franklin and Jackie Wilson. He triumphantly returned to the UK and again found no one interested in his songs, including a newly-written piece Gold thought was a sure-fire hit.

By '75, Amoo had left the Chants and was working with his younger brother Chris, Ray Lake and Dave Smith in a new group called The Real Thing, and their luck turned at last. Tony Hall, a classic British theatre impresario, began managing them, and Hall, looking for decent material for his group, got in touch with Ken Gold and asked if he had anything. The result was The Real Thing's take on Gold's "You to Me Are Everything," a lovely pop-soul record that became an enormous UK hit in 1976, the first number-one hit by a black British group.

And naturally, the single flopped in the U.S., only hitting #64 on the pop charts. Released in June 1976; on Very Best Of.

Punk rock, American style, began as an excavation, with a generation of bored kids digging up the pop music that had been buried by FM radio and album-oriented rock--Phil Spector singles, surf rave-ups, girl-group hits, garage rock LPs. Taking these records (and the sado/masochism, violence and general trashiness that was beneath the surface of a lot of them) as their cues, the new bands remade the past in their own image.

"X Offender" was the first single released by the New York band Blondie, who likely need no introduction. Chris Stein, guitarist and longtime companion to singer Debbie Harry, described the song as being "vaguely biographical--a homage to Spector." Originally called "Sex Offender" and produced by Richard Gottehrer (who had been part of the Strangeloves), it's a giddy ode to bondage, fetishism, policemen fantasies and other joys.

Recorded in New York and released in May 1976 as Private Stock 097. On Definitive Story of CBGB.

The Ramones (who really, really need no introduction) were Blondie's counterweight--goony where Blondie was glamorous, brutal where Blondie was campy. Queens' finest cultural export, the band formed in 1974 and made the Bowery club CBGB's into, for a time, a stage for the entire world.

"I don't get the Ramones," a high school friend once said (one who was into Rick Wakeman and Marillion records, mind). "It all sounds like it could have been recorded in a garage somewhere." Which, I suppose, was the best compliment the band could have ever received.

"Listen to My Heart," a track in which the Ramones come close to their bubblegum roots, is one of the lesser-played tracks off their first record The Ramones, which was recorded in New York between February 2-19 for $6,200, and released in April 1976.

Joey, Johnny and Dee Dee Ramone have all died over the past six years, which really is one of the more depressing facts to recount.

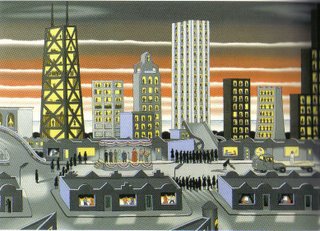

Brown, The Entry of Christ into Chicago in 1976.

For me, the greatest group of the Seventies is a trio of jazz musicians whose work, thirty years later, remains almost utterly ignored. When I was collecting their records in the late '90s, I once thanked a fellow who sold me an LP, as the thing was in near-mint condition. "Yeah, that's the great thing about those avant-garde jazz records--no one ever played them, so they're all in sweet shape," he wrote back.

Air was Henry Threadgill, who, like Anthony Braxton, could play nearly everything under the sun, ranging from the alto saxophone to a device he called the "hubcaphone," a sort of gamelan made out of hanging hubcaps; the bassist Fred Hopkins, the true heir to Charles Mingus; and the brilliant drummer Steve McCall. All three were born in Chicago, and all became affilated with the AACM in the '60s.

By 1975, the trio, along with a lot of their Chicago colleagues, had moved to New York, where the jazz loft scene was raging. In the days before NYC's gentrification, places like TriBeCa were wastelands in which anyone could rent a huge loft for peanuts, and so these lofts became jamming sites, recording studios and rehearsal halls for jazz musicians who in some cases had nowhere else to go.

Air began recording in '75, and "Midnight Sun," off their second record in 1976, shows what the band was routinely capable of. While Threadgill's alto sax playing is compelling, it's Hopkins and McCall (both of whom died in the late '90s) who give the track its guts. Hopkins' bass comes to dominate the performance, doubling with Threadgill the six-note figure that serves as the piece's motif, then repeating the figure while Threadgill solos. Hopkins' solo, supplemented by cannonfire from McCall, sounds like a giant snapping ropes.

Recorded in New York on July 15, 1976; on the Why Not LP Air Raid.

The state of the Air catalog is pretty pitiful. The first two records, Air Song and Air Raid, have never been released on CD, while 1977's Air Time appeared briefly (I saw it in Tower Records once, though it might have been a bootleg); their first major-label record, 1978's Open Air Suit, was never put out on CD, and 1979's Air Lore, their finest record, appears on disc once in a blue moon. Needless to say, the final records from the early 1980s are out of print also. If ever anyone was in need of a good CD anthology, this band is just crying out for it.

"Someday a real rain will come"

*edited, see comments.

No comments:

Post a Comment