Duke Ellington and Billy Strayhorn, Johnny Come Lately.

Duke Ellington and Billy Strayhorn, Tonk.

If you had been lucky to attend a party to which Duke Ellington and his songwriting partner, Billy Strayhorn, had been invited, you might have heard something like these tracks. After a few cocktails, when the party had slowed down, Ellington and Strayhorn would sit together at the piano (if you invited Duke to a party, you'd better have a piano) and play some four-handed duets.

Strayhorn, composer of "Take the A Train", "Chelsea Bridge", and hundreds of other Ellington songs, was for Ellington "the other half of my heartbeat," as Duke put it. The two men had become a joint compositional mind, able to answer each other's improvisational questions the second they were asked. You can hear it in the duets, in which it's almost impossible to determine who is playing what, other than that Ellington often starts the melody and Strayhorn usually plays the sprightlier phrases.

In late 1950, Ellington and Strayhorn recorded eight piano duets--these were completely casual, improvised recordings, produced by Ellington's son Mercer and critic Leonard Feather. Nowhere else was the relationship between Ellington and Strayhorn so wonderfully exemplified.

"Tonk", according to Feather, was a popular party favorite and the only one of the duets that had even the slightest bit of arranging to it. Strayhorn's "Johnny Come Lately", like most of the duets, was recorded spontaneously one day--Ellington and Strayhorn just sat down and played, the tapes rolled.

The Strayhorn/Ellington duets have had a cursed release history. The duets were put out as Mercer Ellington's label's first-ever release, a 10-inch LP, which was soon deleted when the Mercer label went kaput. In the mid '50s, most of the Mercer label's master tapes were consumed in a fire, including those of the duets. In 1964 Riverside, using copies of the original Mercer 10" LP, released all the duets on an LP that would prove to be the label's very last release, and one not widely distributed.

Both "Tonk" and "Johnny Come Lately" were recorded in November 1950, with either Wendell Marshall or Joe Shulman on bass. You can find all the piano duets on Great Times. To be honest, the sound of this CD (remastered in 1989) is tinny and weak. The LP that I took the tracks from, The Golden Duke, (Prestige P-24029), sounds 100 times better--those happy few with turntables can find it secondhand pretty easily.

A lengthy historical intrusion:

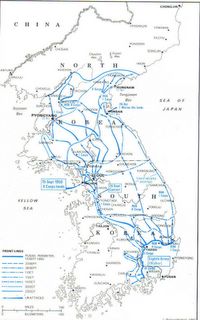

At 4 AM on a rainy Sunday morning, 25 June 1950, South Korean troops along the border between North and South Korea were dozing in happy disarray, as many of their officers had taken weekend passes and lay asleep far from the front. And then, at once, in one consecutive sweeping motion, the North Korean army smashed through the 38th Parallel across the waist of the Korean peninsula, demolishing the South Korean army, and within a month controlled all of Korea but for a half-circle around Pusan, in the southeast corner.

The Korean War is one of the 20th Century's most critical and most forgotten wars, now mainly remembered in the U.S., if at all, as the backdrop to the TV series "M.A.S.H." (and in which Korea substituted for Vietnam).

Korea was one of the unfortunate hinges of the postwar world, a place where the tectonic plates of the USSR and the West ground together. Korea had been controlled by Japan from 1905 to 1945, and after the war, was divided between a Soviet-approved dictator in the North and a U.S.-approved dictator in the South. The 38th Parallel, chosen for its latitudinal simplicity as a dividing line between the two new countries, was nowhere as clean on the ground, severing cities, lakes, properties, families.

A historical irony is that at the time of the dismembering of Korea, the North was the country's industrialized section, which had regarded the agricultural South as a grubby backwater. 55 years on, the roles have reversed, to put it mildly.

The first year of the war was complete bedlam. Two days after the invasion, the U.S. (gaining UN approval) pledged to come to the South's defense. In September, Gen. Douglas MacArthur landed troops in Inchon,a port city behind enemy lines, and soon pushed the Northern forces back up to the Chinese border (going far beyond the UN mandate, which simply called for a restoration of the 38th Parallel border).

This overreach was in part due to MacArthur's delusion (shared, or at least condoned, by Truman) that he could remake the entire Korean peninsula into a Western-friendly client state, as he had just done with Japan, and that the Chinese would allow this to happen on their doorstep. So China's decision to send in an army of "volunteers" (also, during the chaos, China decided to invade and annex Tibet) seems all too predictable in hindsight. The Chinese-backed North Koreans (literally--the Chinese would make the Koreans form the front lines and take more casualties) again almost overran the South until Gen. Matthew Ridgway, the finest American commander of the war, managed to push the North Koreans back to roughly the old North/South border. (Civilization owes Ridgway a small debt of thanks--his ability to stabilize South Korea deflated the argument that the U.S. should drop nuclear bombs on Korea and China.)

So by year's end, things stood almost as they had that rainy morning in June, but for the hundreds of thousands of dead and the country now in tatters. This Quicktime map sums up the back-and-forth. (Found on this site.) It would take another three years to end the war.

Total killed: 415,000 South Koreans, 520,000 North Koreans, possibly 900,000 Chinese, roughly 54,250 U.N forces. And an unspecified, horrific number of civilians, possibly as many as four million. Needless to say, the country was nearly annihilated--at least half of Korea's industry was destroyed and one in three homes were leveled. Curtis LeMay: "We eventually burned down every town in North Korea... and some in South Korea too. We even burned down Pusan -- an accident, but we burned it down anyway."

Korea was the first US conflict to feature interracial units. It wasn't an easy transition.

"There was one in particular, Beard. He was just a simple, die hard, worthless redneck peckerwood. I'm telling it like it is. He was just a die hard that would not bend. He was in the Military Highway Patrol and he flipped his car in snow on the highway and he died. All the black soldiers were applauding like crazy. They was walking around chuckalucking beer, and those that didn't drink was chackalucking soda. And I was one of them, cause I was glad to see him gone. But looking back it was a horrible thing to do, because I was only 22 years old then, and as I matured, I realized through reading and going to school that any man's death diminishes me because I am involved in man-kind. I think it was Sir Francis Bacon who wrote that. And I'm sorry, but he was such a pain in the butt."

from "When Black is Burned", an amazing history of black soldiers in Korea.

An oral history of U.S. veterans of the Korean War.

Films of ’50.

In a Lonely Place. Probably Nicholas Ray's best film, which is to say, about as good as it gets. "It was his story against mine, but of course, I told my story better."

Rashômon. By this point, Kurosawa could have filmed the Old Testament and improved upon the original.

Wagon Master. John Ford’s favorite of his films.

The Asphalt Jungle. “Crime is only a left-handed form of human endeavor.” Marilyn Monroe becomes immortal in ten minutes.

Sunset Blvd. A funeral for the golden age of movies, with Buster Keaton and Erich von Stroheim as pallbearers and Gloria Swanson as the deranged widow; a poisoned dagger aimed straight at Hollywood’s spine.

All About Eve. "Tell me this, do they have auditions for television?" "That's all television is, my dear, nothing but auditions."

Panic in the Streets. A thriller whose biological terrorism fears are all too contemporary; the young Jack Palance, a study in cinematic virility, dominates the film without even intending to.

Winchester ’73.

Les Enfants Terribles.

La Ronde.

And that's it for 1950. Look for 1951 to begin sometime in mid-May, whenever I've unpacked enough records.

The next two weeks will feature a bunch of songs united by a theme, and some will be shockingly modern for this site. Hope you enjoy. Starts Monday.

No comments:

Post a Comment